- All Instrument Types

- Indices

- Equities

- ETFs

- Funds

- Commodities

- Currencies

- Crypto

- Bonds

- Certificates

Please try another search

Pascal: The Cost Of Disbelief (Stocks Don’t Get Less Risky)

Blaise Pascal, a brilliant 17th-century mathematician, famously argued that if God exists, belief would lead to infinite joy in heaven, while disbelief would lead to infinite damnation in hell. But, if God doesn’t exist, belief would have a finite cost, and disbelief would only have at best a finite benefit.

Pascal concluded, given that we can never prove whether or not God exists, it’s probably wiser to assume he exists because infinite damnation is much worse than a finite cost.

When it comes to investing, Pascal’s argument applies as well. Let’s start with an email I received this past week.

The risk of buying and holding an index is only in the short-term. The longer you hold an index the less risky it becomes. Also, managing money is a fool’s errand anyway as 95% of money managers underperform their index from one year to the next.

This is an interesting comment as it exposes two primary falsehoods.

Let’s start with the second comment “95% of money managers can’t beat their index from one year to the next.”

One of the greatest con’s ever perpetrated on the average investor by Wall Street is the “you can’t beat the index game.” It is true that many mutual funds underperform their index from one year to the next, but this has nothing to do with their long-term performance. The reasons that many funds, and investors, underperform in the short-term are simple enough to understand if you think about what an index is versus a portfolio of invested capital.

- The index contains no cash

- It has no life expectancy requirements – but you do.

- It does not have to compensate for distributions to meet living requirements – but you do.

- It requires you to take on excess risk (potential for loss) in order to obtain equivalent performance – this is fine on the way up, but not on the way down.

- It has no taxes, costs or other expenses associated with it – but you do.

- It has the ability to substitute at no penalty – but you don’t.

- It benefits from share buybacks – but you don’t.

- It doesn’t have to deal with what “life” throws at you…but you do.

But as I have addressed previously, the myth of “active managers can’t beat their index” falls apart given time.

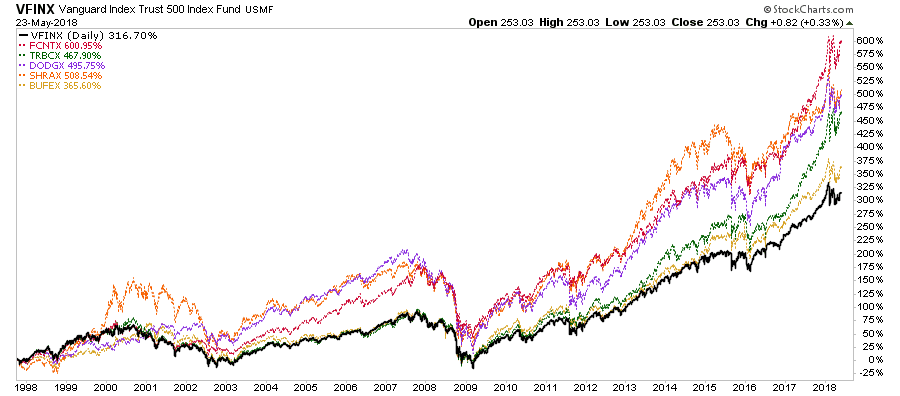

Larry Swedroe wrote a piece just recently admonishing active portfolio managers and suggesting that everyone should just passively invest. After all, the primary argument for passive investing is that active fund managers can’t beat their indices over time which is clearly demonstrated in the following chart.

Oops. There are large numbers of active fund managers who have posted stellar returns over long-term time frames. No, they don’t beat their respective benchmarks every year, but beating some random benchmark index is not the goal of investing to begin with. The goal of investing is to grow your ‘savings’ over time to meet your future inflation-adjusted income needs without suffering large losses of capital along the way.

It isn’t just mutual funds that regularly outperform their respective benchmarks but also hedge funds, private managers and numerous individual investors that put in the necessary time, work and effort.

But, I will admit that today, more than ever, the game is stacked against the average investor as high-speed trading takes advantage of retail investor online order flows. The proprietary trading desks, who have access to massive pools of capital, can push markets on an intra-day basis while computerized programs execute orders based on data flows. It has truly become the battle of “David and Goliath” with Wall Street armed with better technology, more resources, more information, teams of people dedicated solely to a single outcome versus – you and your computer. One can certainly understand why many individuals have given up trying to manage their investments.

But therein lies the huge conflict of interest between Wall Street and you. They need your money flowing into their products so they can charge fees. Wall Street is a business and, for them, business is good, and very profitable, as long as investors buy into the game that investing is the ONLY way to grow “rich.”

However, as investors, we must abandon the idea of chasing some random benchmark index, which really has very little to do with our own personal investing goals, and focus on the things that will make us wealth over time: spend less, save more, reduce debt (increase cash flow), grow our “human capital,” (earning power), invest and avoid major losses.

Investing and avoiding major losses brings us to the first point of the email which is “stocks become less ‘risky’ over time.”

Stocks Become Less “Risky” Over Time?

This idea suggests the “risk” of the loss of capital diminishes as time progresses.

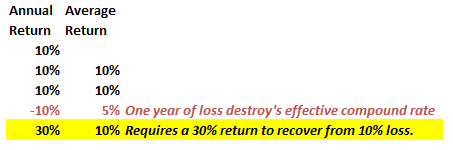

First, risk does not equal reward. “Risk” is a function of how much money you will lose when things don’t go as planned. The problem with being wrong is the loss of capital creates a negative effect to compounding that can never be recovered. Let me give you an example.

Let’s assume an investor wants to compound their investments by 10% a year over a 5-year period.

The “power of compounding” ONLY WORKS when you do not lose money. As shown, after three straight years of 10% returns, a drawdown of just 10% cuts the average annual compound growth rate by 50%. Furthermore, it then requires a 30% return to regain the average rate of return required. In reality, chasing returns is much less important to your long-term investment success than most believe.

The problem with following Wall Street’s advice to be “all in – all the time” is that eventually you are going to dealt a bad hand. By being aggressive, and chasing market returns on the way up, the higher the market goes the greater the risk that is being built into the portfolio. Most investors routinely take on more “risk” than they realize which exposes them to greater damage when markets go through a reversion process.

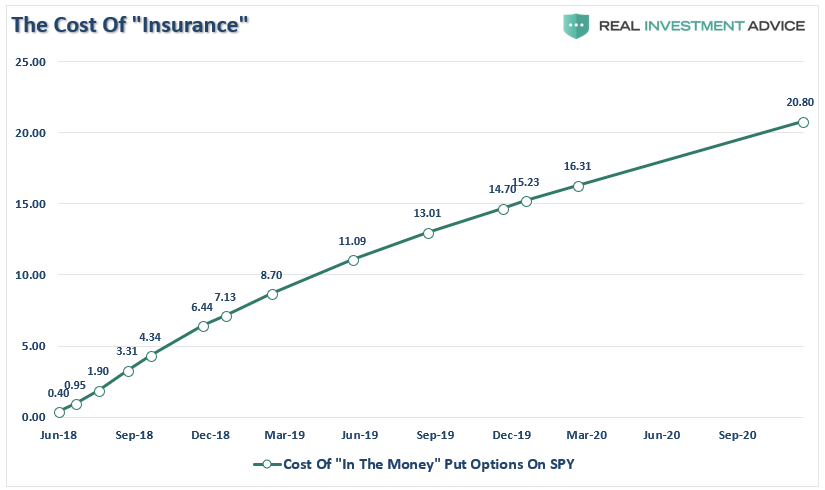

How do we know that risk increases over time? The cost of “insurance” tells us so. If the “risk” of ownership actually declines over time, then the cost of “insuring” the portfolio should decline as well. The chart below is the cost of “buying insurance (put options) on the S&P 500exchange-traded fund.

As you can see, the longer a period our “insurance” covers the more “costly” it becomes. This is because the risk of an unexpected event that creates a loss in value rises the longer an event doesn’t occur.

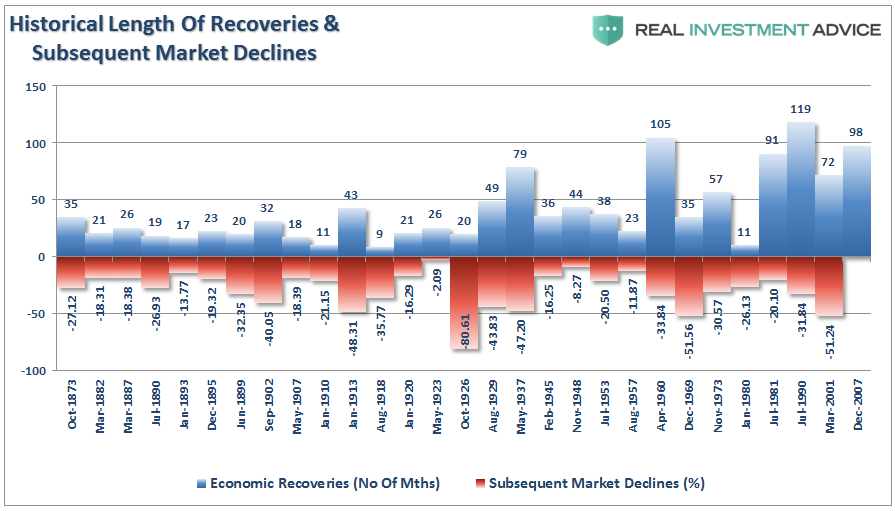

Furthermore, history shows that large drawdowns occur with regularity over time.

Byron Wien was asked the question of where we are in terms of the economy and the market to a group of high-end investors. To wit:

The one issue that dominated the discussion at all four of the lunches was whether or not we were in the late stages of the business cycle as well as the bull market. This recovery began in June 2009 and the bull market began in March of that year. So we are more than 100 months into the period of equity appreciation and close to that in terms of economic expansion.

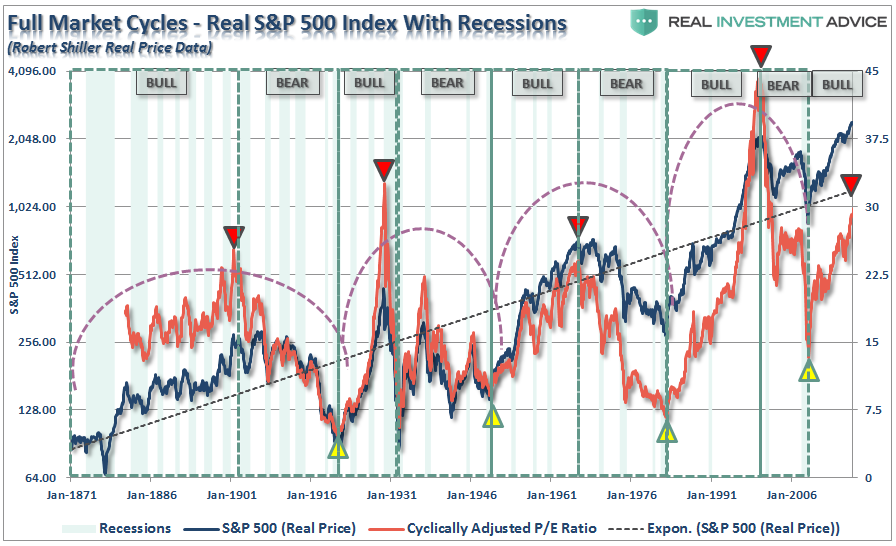

Importantly, it is not just the length of the market and economic expansion that is important to consider. As I explained just recently, the “full market cycle” will complete itself in due time to the detriment of those who fail to heed history, valuations, and psychology.

There are two halves of every market cycle.

In the end, it does not matter IF you are ‘bullish’ or ‘bearish.’ The reality is that both ‘bulls’ and ‘bears’ are owned by the ‘broken clock’ syndrome during the full-market cycle. However, what is grossly important in achieving long-term investment success is not necessarily being ‘right’ during the first half of the cycle, but by not being ‘wrong’ during the second half.

With valuations currently pushing the 2nd highest level in history, it is only a function of time before the second-half of the full-market cycle ensues.

That is not a prediction of a crash.

It is just a fact.

But as Mr. Pascal suggests, even if the odds that something will happen are small, we should still pay attention to that slim possibility if the potential consequences are dire. Rolling the investment dice while saving money by skimping on insurance may give us a shot at amassing more wealth, but with that chance of greater success, comes a risk of devastating failure.

Winning The Long Game

In golf, there is a saying that you “drive for show and putt for dough” meaning that it is not necessary to be able to drive a golf ball 300 yards down the center of the fairway – it is the short putting, measured in feet, which will win the game. In investing, it is much the same – being invested in the market is one thing, however, understanding the “short game” of investing is critically important to winning the “long game.”

When valuations rise to rarely seen levels, and the associated risks of a major drawdown increase exponentially, focus on managing the “risk” of the portfolio rather than chasing “returns.”

Investors would do well to remember the words of the then-chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission Arthur Levitt in a 1998 speech entitled “The Numbers Game:”

While the temptations are great, and the pressures strong, illusions in numbers are only that—ephemeral, and ultimately self-destructive.

But it was Howard Marks who summed up our philosophy on “risk management” well when he stated:

If you refuse to fall into line in carefree markets like today’s, it’s likely that, for a while, you’ll (a) lag in terms of return and (b) look like an old fogey. But neither of those is much of a price to pay if it means keeping your head (and capital) when others eventually lose theirs. In my experience, times of laxness have always been followed eventually by corrections in which penalties are imposed. It may not happen this time, but I’ll take that risk.

Client’s should not pay a fee to mimic markets. Fees should be paid to investment professionals to employ an investment discipline, trading rules, portfolio hedges and management practices that have been proven to reduce the probability a serious and irreparable impairment to their hard earned savings.

Unfortunately, the rules are REALLY hard to follow. If they were easy, then everyone would be wealthy from investing. They aren’t because investing without a discipline and strategy has horrid consequences.

Personally, I choose to “believe” as I really don’t like the sound of “eternal damnation.”

Related Articles

While market cap weighting is still the go-to for many investors due to its low cost and low turnover, it's becoming increasingly fragile these days thanks to the concentration...

The oldest ETF, the SPDR S&P 500 Trust, had the most inflows in February. The $14.6 billion in inflows allowed it to surpass the Vanguard S&P 500 ETF. Which ETFs saw the...

Leveraged exchange-traded funds (ETFs) substantially increase the potential reward of an investment by affording investors the chance to generate double or triple the returns of...

Are you sure you want to block %USER_NAME%?

By doing so, you and %USER_NAME% will not be able to see any of each other's Investing.com's posts.

%USER_NAME% was successfully added to your Block List

Since you’ve just unblocked this person, you must wait 48 hours before renewing the block.

I feel that this comment is:

Thank You!

Your report has been sent to our moderators for review

Add a Comment

We encourage you to use comments to engage with other users, share your perspective and ask questions of authors and each other. However, in order to maintain the high level of discourse we’ve all come to value and expect, please keep the following criteria in mind:

Enrich the conversation, don’t trash it.

Stay focused and on track. Only post material that’s relevant to the topic being discussed.

Be respectful. Even negative opinions can be framed positively and diplomatically. Avoid profanity, slander or personal attacks directed at an author or another user. Racism, sexism and other forms of discrimination will not be tolerated.

Perpetrators of spam or abuse will be deleted from the site and prohibited from future registration at Investing.com’s discretion.