What do China, Japan, India, England, Germany… heck, most of the significant economies around the globe, share in common? Bear-market declines in stock prices of 20% or more.

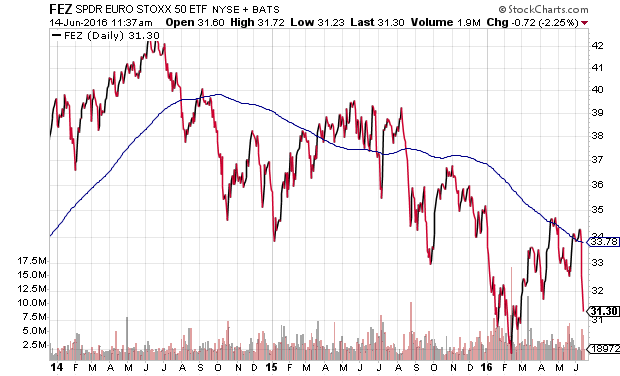

Several ETFs demonstrate the breadth of the global depreciation in equities. For example, SPDR EURO STOXX 50 (NYSE:FEZ) illustrates the doggedness of the downtrend in Europe. The pattern has persisted since the summer of 2014.

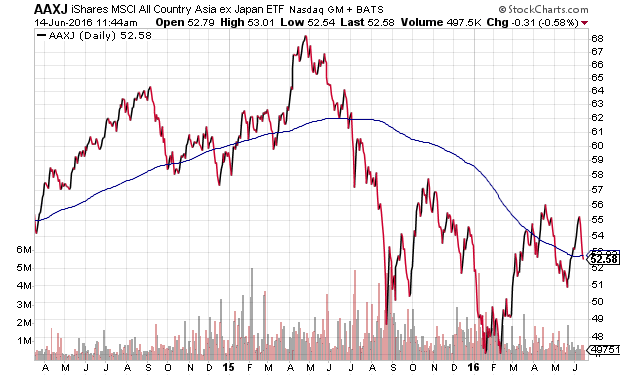

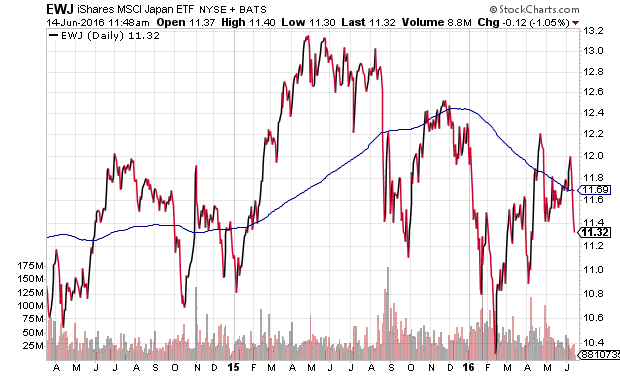

Meanwhile, iShares MSCI All-Country Asia ex Japan (NASDAQ:AAXJ) highlights the struggles in the Pacific, and iShares MSCI Japan (NYSE:EWJ) shines a light on the sell-off in shares of Japanese companies. Selling pressure has been battering Asian stocks since May of 2015.

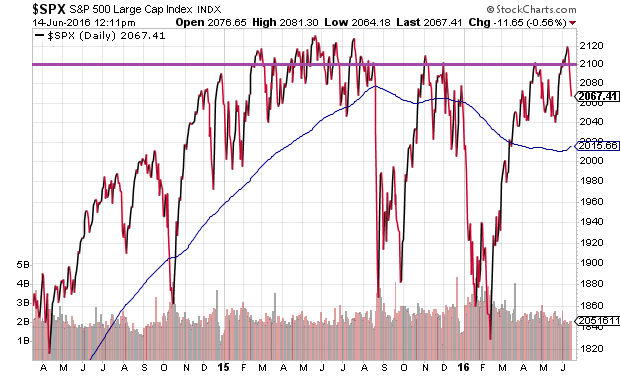

Major U.S. benchmarks like the S&P 500 have managed to dodge a similar fate. The popular gauge of U.S. large-capitalization stocks has rallied back from 10%-plus corrections in August-September (2015) as well as January-February (2016).

On the other hand, Mike Antonelli at Robert W. Baird & Co. pointed out that the heralded index has climbed back above 2,100 on 30 separate occasions, only to retreat back below the level shortly thereafter. What’s more, the S&P 500 has not been able to surpass its record peak of 2,130 (May, 2015) in nearly 13 months. That’s a whole lot of futility.

Perhaps ironically, the resilience of U.S. large caps has led some investors down a reckless path of price insensitivity. They do not care how obscenely overvalued U.S. stocks may be on a wide array of long-standing metrics. They have little interest in the feeble economic backdrop either. What do those in the exuberant crowd tend to hang their hopes on? Foolishly, they cite, “It’s time in the markets, not timing the markets.”

Sadly, these folks do not know that the wildly celebrated catchphrase emanated from Wall Street marketers. For instance, a recent college teacher who used to teach personal finance (of all things) recently cited to me the Invesco fund family study on how missing the “10 best days” of the market each year would result in wiping out virtually any gains over a longer-term horizon. (Ugggggh… where do I begin!)

First of all, Wall Street firms from Fidelity (NYSE:FNF) to Invesco (NYSE:IVZ) have a vested interest in making certain that you are always invested. That is why the Wall Street marketing machine pushed, “It’s time in the markets, not timing the markets.” Fund families make their money on commissions and internal expenses associated with you staying right where you are. They need assets under management; they cannot afford to let you sell. The same holds true for the financial media that generate revenue from advertising dollars from… yep, you guessed it… Wall Street financial companies.

Second, it is ridiculous to assume that when you choose to reduce some of your exposure to stocks that you’re only going to miss out on the wonderful bull market up days. If you’re out, you’re going to miss plenty of the unbelievably awful days as well. One is not capable of tragically missing out on all of the great days, nor is one capable of deftly avoiding all of the devastating down days.

It follows that a person may be better served by understanding the ramifications of missing the “10 best days” AND the “10 worst days” versus holding-n-hoping every position. Or how about missing the “25 best days” AND the “25 worst days” versus holding everything you own. Or missing the “50 best” AND 50 worst.” Or even, missing the “10 best quarters” AND the “worst 10 quarters.”

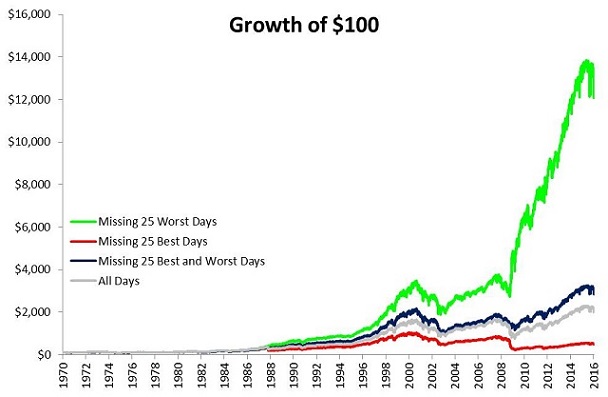

So, let’s evaluate facts that Wall Street tries to keep from you with a look at the S&P 500 since 1970. As stipulated before, nobody is going to perfectly miss only the 25 best days in each year of a market, anymore than he/she will miraculously miss the 25 worst days in the market. That said, one thing should still stand out in the chart below – something that Wall Street never mentions. As shown by the growth of the green line, missing the bad times is far more critical than missing out on those good times.

Other than identifying the reality that missing bearish days is more critical than missing bullish ones, the real focus should be on the difference between “All Days” and “Missing the Best 25 and Worst 25.” Why is this important? Primarily, because the fallacy of “it’s time in the markets, not timing the markets” doesn’t hold up. You do not need to be an evil market timer to recognize that you can miss a whole lot of good days alongside the bad ones. The result? Better than being all in at all times.

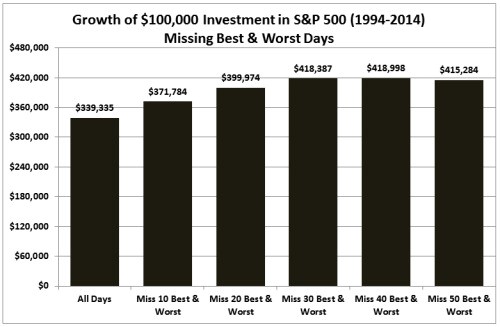

The same findings have been replicated over and over. The folks over at Stock Trader’s Almanac found that the effect of missing the “50 Worst Days” is substantially more powerful than missing the “50 Best Days.” (Not that you’d hear this from the “it’s time in the market” Wall Streeters.) Again, however, the more powerful message is the reality that missing BOTH the “50 Worst” and “50 Best” outperformed buy-n-hold between 1994 and 2014.

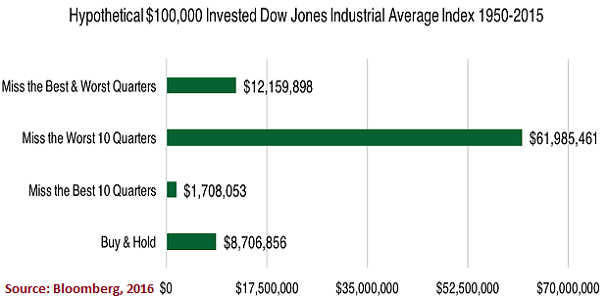

Still not convinced that buying-n-holding all market days could be problematic? Here is yet another look at 65-plus years of data on the Dow Jones Industrials. Once again, the media and Wall Street would want you to focus only on “buy-n-hold” at all times as it relates to missing the best three-month periods since 1950. And sure, if you managed to miss the 10-best quarters since 1950, you would have done far worse than had you simply stayed in the Dow through thin and thick.

However, that is only HALF the story. Side-stepping the 10-worst quarters since 1950 had a far more powerful effect. Again, it would not have been able to do so, but it would not have been feasible to have only missed the 10-best quarters either. Most critically? Missing the best quarters and missing the worst quarters over 65 years dramatically outperformed buy-n-hold.

The take-home? Minimizing monstrous losses is far more critical to creating and maintaining long-term wealth than chasing returns via Wall Street’s tag-line, “time in the markets, not timing the markets.”

Even the notion that there are only two ways to invest – angelic buy-n-hold or unrighteous market timing – is preposterous. If you sell any asset ever, you have made a timing decision. If you buy any asset ever, you have made a timing decision. If you rebalance your portfolio quarterly or semi-annually or annually, that is a timing strategy. If you dollar-cost average, mechanical or not, it involves timing.

Personally, I see benefits to pruning winners back to original portfolio weights. Is rebalancing a form of evil market timing? I see benefits in selling positions that have not progressed as I may have initially surmised. Is cutting bait to continue fishing a timer’s mistake, or is taking a small loss to avoid a bigger one a quintessential principle of insuring one’s well-being? And if the combination of both of these activities provides cash, might it be sensible to hold the cash for an opportunity to “buy lower?” Or must one plow all of his capital back into a buy-n-holder’s paradigm?

When stocks are exceptionally overvalued on a fundamental basis, when the FTSE Multi-Asset Stock Hedge Index is hitting “higher highs,” when risk-off assets like Treasury bonds outperform stocks for 6 months, 12 months and 18 months, when stagnation threatens domestic and foreign economies, I reduce the percentage exposure to stocks. I also reduce the percentage exposure to any bonds that do not qualify as investment grade. Moreover, I make sure that the holdings themselves are low volatility securities with relatively strong balance sheets.

My clients prefer some time out of the markets… and we are not talking about 100% in or 100% out. They recognize that some time out of the markets during the tech wreck (2000-2002) and the financial crisis (2007-2009) was beneficial to maintaining their standard of living going forward. Then, like now, some dry powder in the form of cash/cash equivalents helped reduce volatility. Then, like now, cash is how one can acquire desirable assets at lower prices down the road.