High profile market watchers have pointed out that there have only been four times in the last nine decades when back-to-back calendar year stock declines occurred. The years? 1929-1932, 1939-1941, 1973-1974, and 2000-2002.

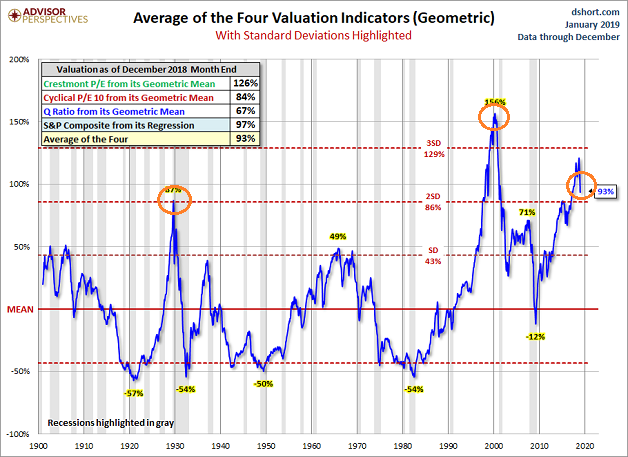

This could be encouraging news for stock enthusiasts were it not for the fact that 1929-1932 and 2000-2002 are included in the list. Valuation levels today have some of the same features that they did leading into the Great Depression and heading into the turn-of-the-century tech bubble.

There’s another reason that the infrequency of back-to-back calendar year declines fails to inspire. Specifically, an arbitrary time stamp ignores the basics of bear market math.

Consider the reality that stocks fell 38% in 2008 alone. They fell more than 50% in the 10/07-3/09 financial collapse. Calendar year stats notwithstanding, the depth of bearish stock price depreciation required four-and-a-half years for recovery. Note: The 100%-plus recovery time would likely have taken seven years had it not been for the amount of electronic credit stimulus (a.k.a. “quantitative easing” or “QE”).

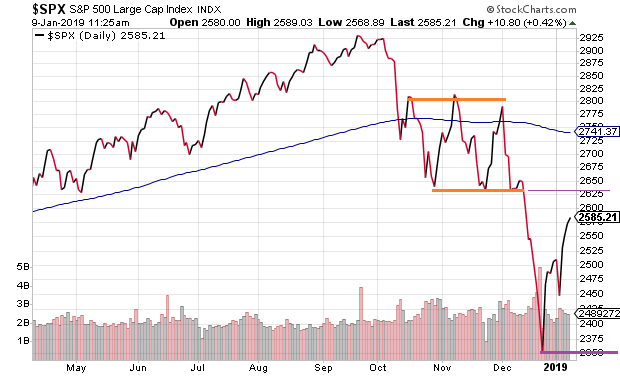

It is true that the S&P 500 has bounced mightily off of resistance near 2350. Indeed, many a computer has been set on a course to buy at that level, if for no other reason that a closing price of 2344 would usher in an official stock bear.

Technical analysts appear split on whether or not the correction lows will be “retested.” My opinion? The S&P 500 could struggle to break through and hold the 2625-2650 are of resistance. This would likely lead to revisiting the 2350 lows at some point in the first quarter of 2019.

There are a few tailwinds to help stocks rally. The government shutdown will likely end with some sort of compromise. Meanwhile tariff tantrums and trade skirmishes are likely to see some sort of resolution rather than a full-fledged trade war.

However, many folks are missing a bigger picture. Here’s where they’re getting it wrong:

(1) Global Slowdown. If you believe as I do that stock market depreciation precedes economic contraction, and not the other way around, than the declines around the world may be telling. Both the Stoxx Europe 600 and the U.K.’s FTSE 100 eroded 13% in 2018. Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average fell 12%.

More notably, the Shanghai Composite finished 2018 down 25%. That was the steepest loss for Chinese equities since 2008. Keep in mind, factory activity in China is at its lowest ebb in three years, while manufacturing activity actually contracted.

Granted, near-term predictions for the U.S. economy remain relatively robust. Yet, can the U.S. continue to act in a vacuum where diminishing foreign growth does not adversely impact S&P 500 corporate earnings? Will “fully employed” Americans with a propensity to spend and consume offset the Federal Reserve’s credit-restricting policies of rate hikes and quantitative tightening (QT)?

(2) Fed Policy Error. The Fed is tightening in more ways than one — hiking the overnight lending rate as well as reducing its balance sheet via QT. And that’s dangerous.

We should actually acknowledge at this point that the monetary policy error has already occurred. What do I mean by that? Manipulating the cost of capital lower for too long was the humongous mistake that led to the housing crisis and concurrent subprime mortgage disaster. Ironically enough, the Fed “fixed” the problem by manipulating the cost to borrow even lower for even longer.

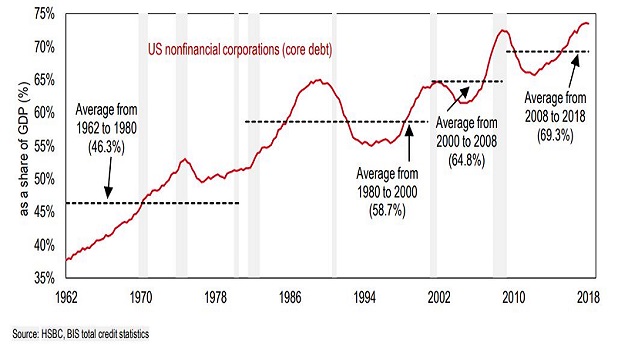

Now we have the most dangerous profile of corporate credit risk on record. Not only is one-half of the “investment grade” corporate debt market rated a mere one notch above “junk” (BBB), but nonfinancial corporate debt-to-GDP has never been as ominous.

Although the real policy error was manipulating borrowing costs into the basement and keeping them down there for eight-plus years, the near-term mistake will be the aggressive quantitative tightening (QT). In fact, it’s not truly a surprise that the Q4 shift toward erasing $50 billion per month in balance sheet electronic credits corresponded to the rapid retreat from all-time highs in the stock market.

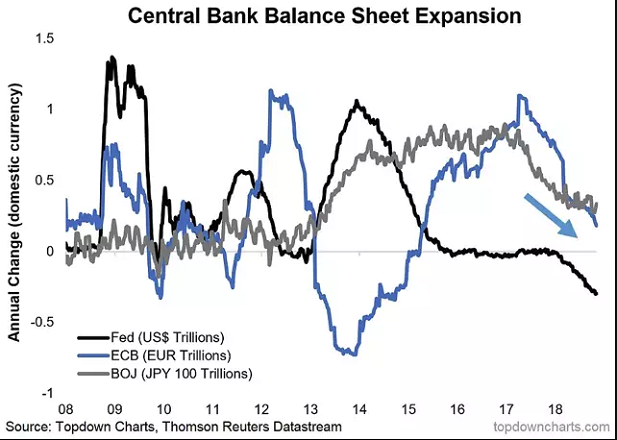

Here in Q1 of 2019, there’s some excitement that the Fed will stop raising the overnight lending rate soon. I would not be excited to take on more stock risk until the Fed stops balance sheet reduction AND, eventually, eases aggressively with QE. As it stands, when one combines the balance sheet stimulus of the major central banks around the globe, Q1 of 2019 marks the moment when collective stimulus turns negative (a.k.a. “quantitative tightening”).

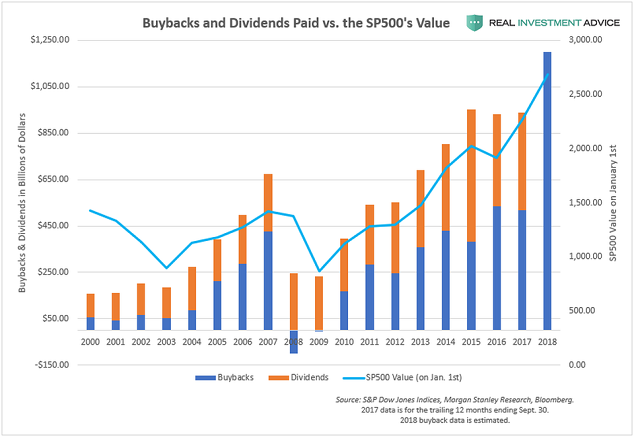

(3) Bye Bye Buybacks? The current corporate debt balloon is a function of the Fed policy error that manipulated rates lower for nearly a decade. For the most part, public companies used the money borrowed in the bond market to acquire respective shares in the stock market.

Take a peek at how buybacks have steadily climbed since the Great Recession ended in 2009. Similarly, the money saved via tax reform legislation in 2017 led to an epic buyback binge in 2018. Considering how poorly equity assets and most financial assets fared in 2018, how much worse would the U.S. stock market have performed if corporations hadn’t been buying shares by the boatload all year long?

It is not clear whether or not buybacks will continue on a upward trajectory to support respective corporate shares. Companies that are smitten with enhancing the perception of their earnings per share (EPS) may continue to plow dollars saved in taxes back into stocks.

On the other hand, the ability to borrow for the same purpose is already coming under pressure. And executives may find themselves becoming squeamish about throwing good money after bad if prices continue to fall. Indeed, many of those BBB-rated companies may need to “stockpile” some cash for a rainy season to keep paying debts. Meanwhile, other companies may decide that capital expenditures may make more sense for real growth over artificially engineered growth.

Bottom line? Market choppiness may be the norm for an extended period. Keep in mind, October was disastrous, while November experienced relief. In the same manner, December was abysmal, whereas January has been showing signs of rehabilitation.

Our tactical allocation to equity risk is significantly below our top targets. Aggressive growth clients have closer to 75% in early cycle uptrends, though they have approximately 50% at present. Moderated growth and income clients have closer to 60%-65% in early cycle uptrends, whereas they have closer to 35%-40% at the moment. More conservative growth and income clients usually have 45%-50% in early cycle uptrends, while they have roughly 30% today.

The January rally may continue. After all, the Fed is hinting at a rate-hike pause and political squabbles will not derail the near-term enthusiasm.

Nevertheless, the rally will come back under pressure. Global economic weakness, aggregate central bank quantitative tightening as well as executive trepidation on buyback efficacy are realities that cannot be swept under the bear skin rug.

Disclosure Statement: Gary Gordon, MS, CFP is the president of Pacific Park Financial, Inc., a Registered Investment Adviser with the SEC. Gary Gordon, Pacific Park Financial, Inc., and/or its clients may hold positions in the ETFs, mutual funds, and/or any investment asset mentioned above. The commentary does not constitute individualized investment advice. The opinions offered herein are not personalized recommendations to buy, sell or hold securities. At times, issuers of exchange-traded products compensate Pacific Park Financial, Inc. or its subsidiaries for advertising at the ETF Expert website. ETF Expert content is created independently of any advertising relationship.

Which stock should you buy in your very next trade?

AI computing powers are changing the stock market. Investing.com's ProPicks AI includes 6 winning stock portfolios chosen by our advanced AI. In 2024 alone, ProPicks AI identified 2 stocks that surged over 150%, 4 additional stocks that leaped over 30%, and 3 more that climbed over 25%. Which stock will be the next to soar?

Unlock ProPicks AI