Readers know that I haven’t shied away from stressing over the Federal Reserve’s tightening. As a firm believer in the Austrian Business Cycle Theory – first drafted by Ludwig Von Mises in early 1900’s – I believe that artificially moving interest rates away from the markets natural rate is opening Pandora’s box.

Sure – lowering rates across the yield curve is good for stimulating the economy. And like John Maynard Keynes explained, it’s a good tool for ‘papering over’ a slowdown – a quick fix.

But like Mises said – it’s not the boom that matters (from lowering rates). It’s the bust that will follow (from raising rates).

Suddenly and artificially raising short-term rates – which the Fed does when they hike – disrupts the current equilibrium. Think about it this way: all those borrowers – whether having mortgages, student loans, car loans, credit cards, and even corporations – now must pay more in interest.

Business projects that were barely economic at a 3% interest rate are completely uneconomic at 5%. And mom and dad barely affording their mortgages at 5% won’t be able to at 7%.

Of course these are just a couple of examples. There are many things throughout the economy that will be negatively affected by suddenly raising rates – which will all trigger their own unintended consequences.

That’s the problem with complex systems like the U.S. economy and financial system. Everything’s interconnected.

But there’s one thing from the Fed’s tightening that’s worth mentioning yet again. . . And that’s rising short-term dollar funding costs – which is slowly popping this worldwide debt bubble.

First and foremost, the global dollar shortage – which I’ve written about many times (read here and here) – is a huge threat to the global economy. In fact – I believe it’s the number one overlooked threat out there today.

But it’s a side-effect from the Fed’s tightening. . .

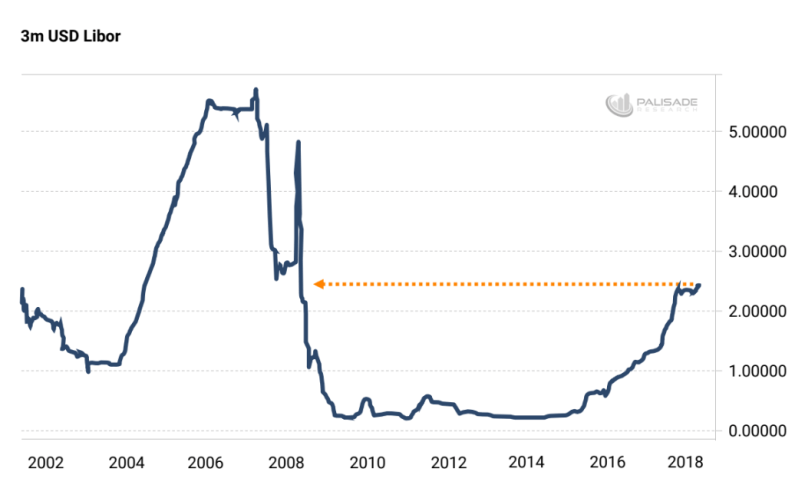

And because of their tightening – the 3-month U.S. dollar LIBOR (London Inter Bank Offered Rate) is at a decade high. Levels not seen since 2008. And expected to continue higher.

Source: ZeroHedge

Now as short-term rates rise – this poses huge risks to the already very-fragile global financial market and asset prices. Especially since so many foreign countries and foreign corporations became addicted to cheap dollar-denominated debt.

For instance – I highlighted this dire problem last week (read here). . .

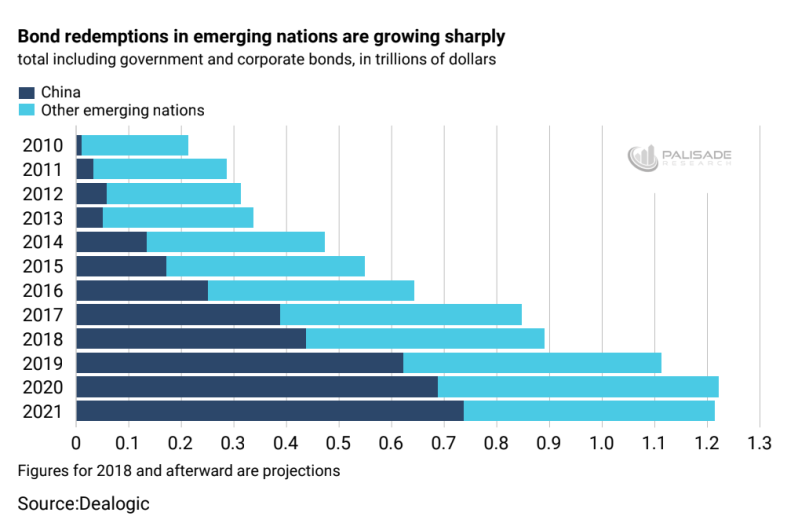

But in summary – the Emerging Market’s (both governments and corporations) have over $3.25 trillion of dollar-denominated debts maturing by 2021.

And there’s a high chance that most of these companies and governments won’t be able to ‘roll their debt over’ (refinance) at these higher short-term rates.

What I mean is: these countries would have to borrow U.S. dollars immediately – thus requiring them to take on higher cost short-term funding (aka ‘float the debt’). And then pay off their maturing debts with the new debt.

The problem is – they’ll be committing a financial sin. . .

Never borrow short and go long.

Think of it this way – imagine you took out a 15-year ‘balloon’ mortgage at 5% during a time when rates were lower. But now – 15 years later – rates are much higher. And you now have to pay off your 15-year mortgage that’s coming due in the next few days.

Problem is – you don’t have the cash to do so. And since financial conditions are tighter – you don’t have easy access to credit anymore. Thus forcing you to visit a Pay Day loan place that charges very high interest rates for immediate cash.

With no better options – you take the money you need to pay off your 15-year mortgage. But now stuck with an 18% interest rate that’s maturing in 90 days.

See how dangerous that loop is? This is basically the place the Emerging Markets are in.

But I’ve written enough about the Emerging Markets and their debt problems. Let’s look at the other effects that a rising short-term LIBOR has. . .

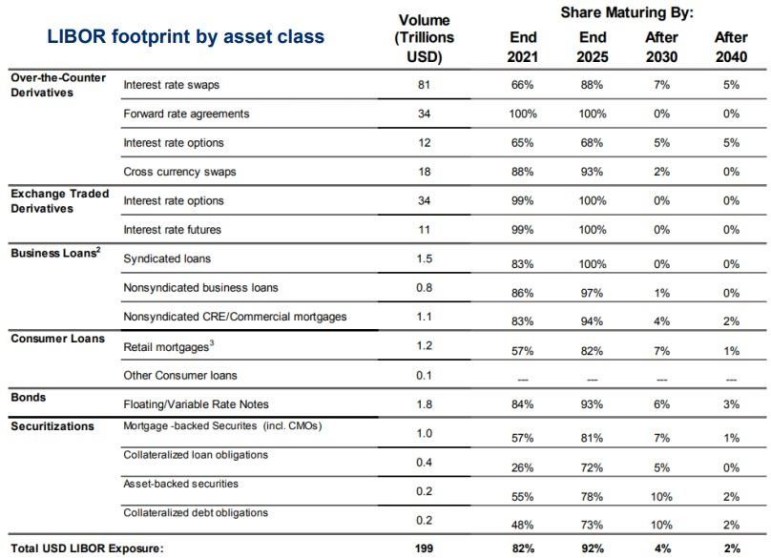

I wrote back in April (click here) about the significance of a rising LIBOR rate – especially since there’s so much debt tethered to it. According to TBAC (Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee) – there’s nearly $200 trillion of assets linked to LIBOR.

And if you add up all the business and household related debts (the business loans, consumer loans, bonds, and securities) – there’s over $8 trillion directly vulnerable to rising rates.

As you can see, most of these debts – 82% – mature in just the next two years (2021) alone. Yet – for some odd reason – TBAC and the market’s not expecting a rising LIBOR to impact the global financial system.

I find this strange – because historically during a rising rate environment – there’s eventually a financial crisis. . . But instead of guessing what will be the straw that breaks the camel’s back (aka the ‘tipping point’), we’re already seeing worrying trends from a rising LIBOR.

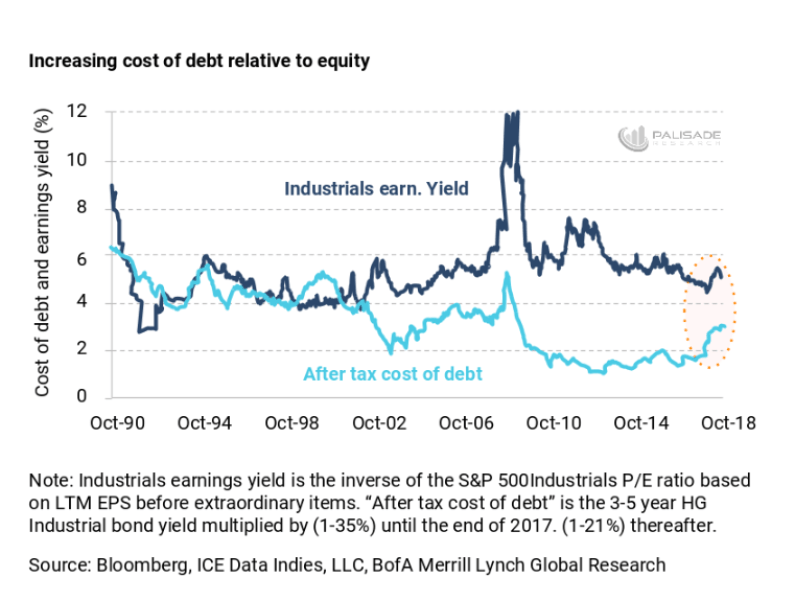

For instance – the cost of debt relative to corporate earnings is already noticeably souring. You can see that the after-tax cost of debt’s much more now.

And at its highest level since the 2008 financial crisis. . .

During the Fed’s post-2008 ZIRP (zero interest rate policy) years, many investors forgot about the ‘I’ in EBITDA – ‘earnings before interest taxes depreciation and amortization’.

When rates were low – interest costs were low. Which then made EBITDA look higher.

But like Alan Greenspan – Former Fed Chairman – said a long time ago: interest payments are the most uncontrollable part since it’s a variable left to the market.

A firm can cut their dividend payout, can cut their capital expenditure costs, can lay off employees. But they can’t control their interest rate. . .

This has dangerous implications for equity prices – especially as short-term rates keep rising. And a key reason I see a very high chance of a global earnings recession sometime in late-2019 (read more here).

Finally – I part with these last words. LIBOR doesn’t move Fed policy. But Fed policy moves LIBOR.

LIBOR’s built from two parts: the overnight-lending rate set by the Fed. And the premium (the spread) above what lenders want for their lending risk. So as long as the Fed continues hiking and tightening – the short-term LIBOR rate will rise.

And we will see households, corporations, foreign governments, and many more squeezed dry.