One question increasingly dominates business-cycle analysis for the US economy these days: How slow can it go without slipping into recession? No one knows the answer… yet. But the latest data shows that growth continues to decelerate, suggesting that the gray area between expansion and contraction may be tested in the months ahead.

For now, US recession risk remains low, based on numbers published to date. The probability is still virtually nil that an NBER-defined downturn has started, as of September. But as detailed below, the forward estimate through November for The Capital Spectator’s main business-cycle benchmark – the Economic Trend Index (ETI) – shows that the macro trend is on track to slip to a three-year low, marking a level that’s perilously close to the neutral 50% mark that separates growth from decline.

Even if the trend continues to slide, a recession probably wouldn’t start until sometime in 2020’s first half. The good news: a lot can happen between now and then, and so it’s premature to assume the worst as fate. Indeed, the possibility that that the economy will stabilize at a slow, perhaps weak pace of growth can’t be ruled out, at least not yet.

In any case, the US is running out of road to sustain further downshifts in output without slipping over to the dark side. Much depends on how a variety of factors unfold, including monetary and fiscal policy decisions in the weeks and months ahead.

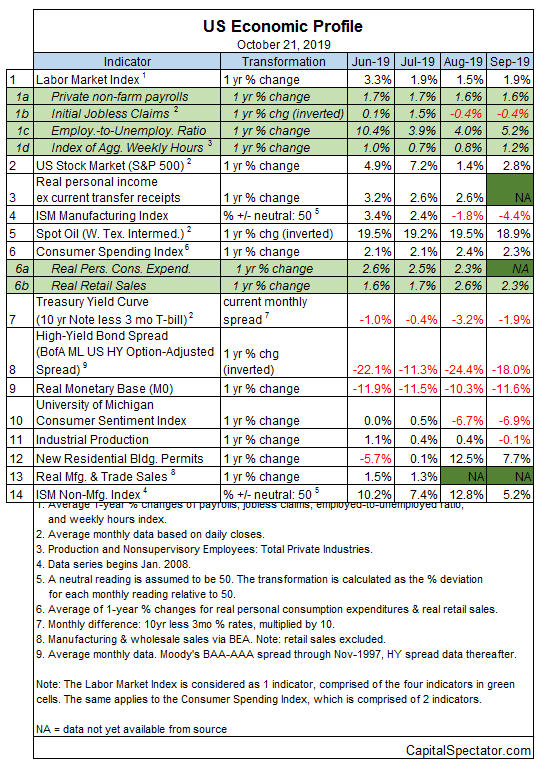

Meantime, let’s review the numbers in hand. Note that today’s update reminds that another indicator for ETI slipped into the red in September (see table below). Industrial production fell fractionally last month vs. the year-earlier level – the first annual decline since 2016.

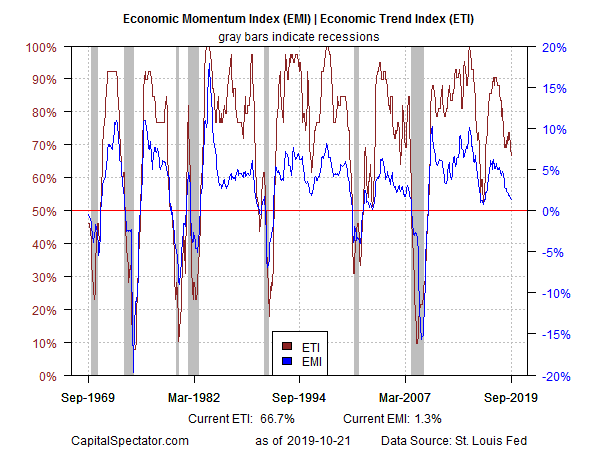

For additional context, consider the aggregated profile of the indicators in the table above via another proprietary benchmark — the Economic Momentum Index (EMI). EMI edged down to a weak 1.3% in September, the lowest since 2016. Although EMI and ETI remained above their respective tipping points that mark recession (50% for ETI and 0% for EMI), a clear downside bias is conspicuous and, as we’ll see below, the projections through November show that further weakening is probably in the cards.

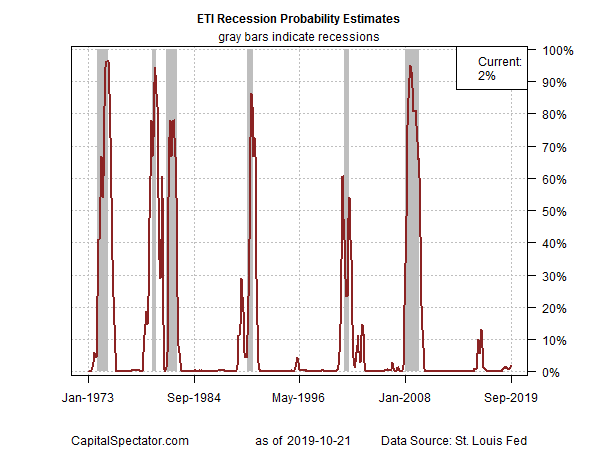

Despite the potential for trouble in the months ahead, the data published to date for ETI continues to show that recession risk remains low, albeit by looking into the rearview mirror through September. Translating the index’s historical values into recession-risk probabilities with a probit model points to low business-cycle risk for the US through last month. Analysis through this lens indicates that the odds remain low — 2% — that NBER will declare September as the start of a new recession. Note, too, that a probit-model reading of EMI (not shown) also shows a relatively low probability (8%) that the economy was contracting last month.

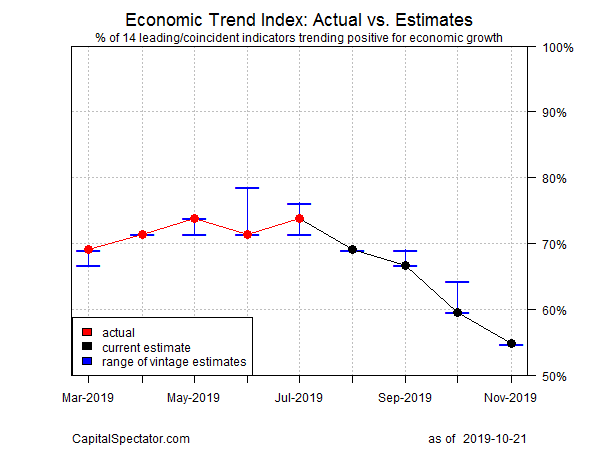

Turning to the near-term outlook, consider how ETI may evolve as new data is published. One way to project values for this index is with an econometric technique known as an autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model, based on default calculations via the “forecast” package in R. The ARIMA model calculates the missing data points for each indicator for each month — in this case through October 2019. (Note that July 2019 is currently the latest month with a complete set of published data for ETI.) Based on today’s projections, ETI is expected to tick lower for a second month in November, slipping dangerously close to the 50% mark. A reading below 50% would formally indicate that the NBER is likely to declare the month as the start of a recession. Note, too, that the revisions to ETI’s monthly values have been on the downside in recent months — another worrisome sign.

Forecasts are always suspect, but recent projections of ETI for the near-term future have proven to be reliable guesstimates vs. the full set of published numbers that followed. That’s not surprising, given ETI’s design to capture the broad trend based across multiple indicators. Predicting individual components in isolation, by contrast, is subject to greater uncertainty. The assumption here is that while any one forecast for a given indicator will likely be wrong, the errors may cancel out to some degree by aggregating a broad set of predictions. That’s a reasonable view, based on the generally accurate historical record for the ETI forecasts in recent years.

The current projections (the four black dots in the chart immediately above) suggest that the economy will continue to expand through next month, albeit at a slowing pace. The chart also shows the range of vintage ETI projections published on these pages in previous months (blue bars), which you can compare with the actual data (red dots) that followed, based on current numbers.

For more perspective on the track record of the ETI forecasts, here are the vintage projections for the past three months:

Note: ETI is a diffusion index (i.e., an index that tracks the proportion of components with positive values) for the 14 leading/coincident indicators listed in the table above. ETI values reflect the 3-month average of the transformation rules defined in the table. EMI measures the same set of indicators/transformation rules based on the 3-month average of the median monthly percentage change for the 14 indicators. For purposes of filling in the missing data points in recent history and projecting ETI and EMI values, the missing data points are estimated with an ARIMA model.