Slow growth continues to dominate the U.S. economic profile, and the trend could weaken further in the months ahead. But the downshift has yet to trigger a credible recession warning. Although some indicators suggest otherwise – including the inverted Treasury yield curve – a broad reading of economic and financial data still points to a modest expansion in the recent past—and for the immediate future.

The caveat in this modestly upbeat analysis is that slow growth is at risk of slipping further, based on a near-term projection of the macro trend (discussed below). But this could turn into a stabilization of slow growth if incoming economic reports dispense better-than-expected numbers for key indicators.

In fact, this week’s August results for industrial production and housing construction delivered exactly that. On both fronts, strong gains surprised economists, reminding that for all the headwinds facing the U.S. economy of late, the capacity for growth hasn’t completely faded, at least not yet.

But the uncertainty tied to the ongoing U.S.-China trade war, along with geopolitical risks in the Middle East, pose headwinds for the economic outlook. The subdued outlook is hardly limited to the U.S. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development today trimmed its outlook for the global economy, predicting that growth will dip to the slowest pace since the financial crisis.

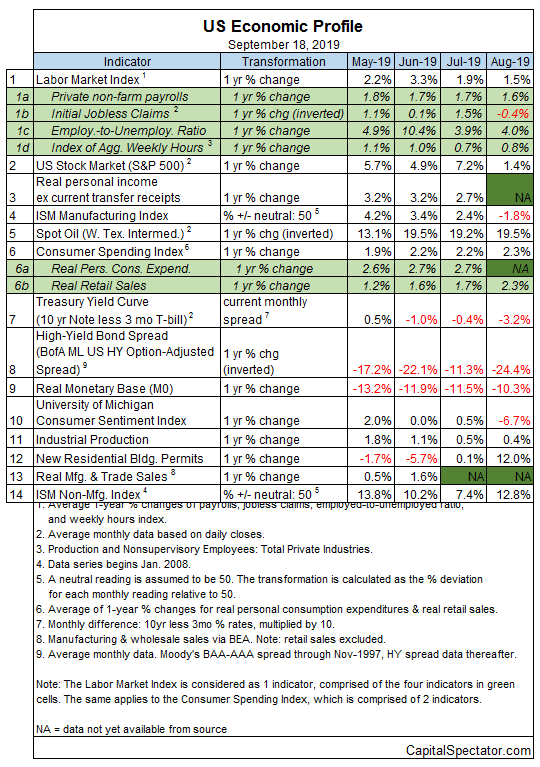

In relative terms, the U.S. compares favorably with the world’s biggest economies. But the American expansion has clearly slowed. The good news: most of the key indicators continue to trend positive, including the critical employment and consumer-spending numbers. Nonetheless, there’s a bit more red ink in the August column (see table below) and so the possibility of further deterioration later in the year can’t be ruled out. Recession risk, in short, could rise from currently low levels.

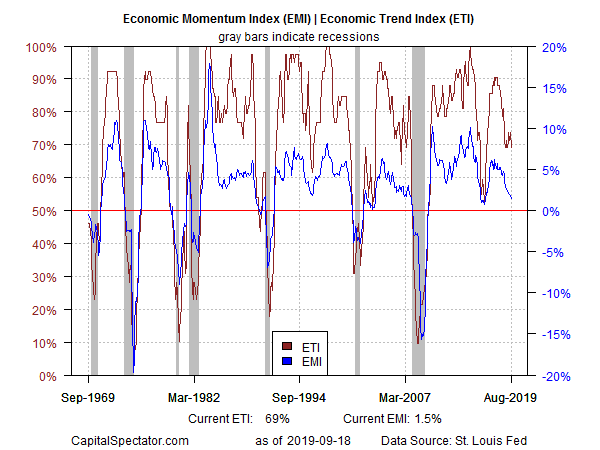

For additional context, consider the aggregated profile of the indicators in the table above via two benchmarks. The Economic Trend Index (ETI) – a business-cycle index that tracks 14 indicators that collectively capture a broad snapshot of U.S. economic activity — ticked down to relatively weak 69% in August (red line in chart below). Filtering the same data set through another econometric lens – the Economic Momentum Index (EMI) – also reflects a softer trend. EMI’s current 1.5% print marks the lowest level in several years (blue line). Both indicators remain comfortably above their respective tipping points that mark recession (50% for ETI and 0% for EMI), but the downside bias of late suggest that the economy’s outlook is cautious at best. (For details on the design and interpretation of ETI and EMI, see my book on monitoring the business cycle.)

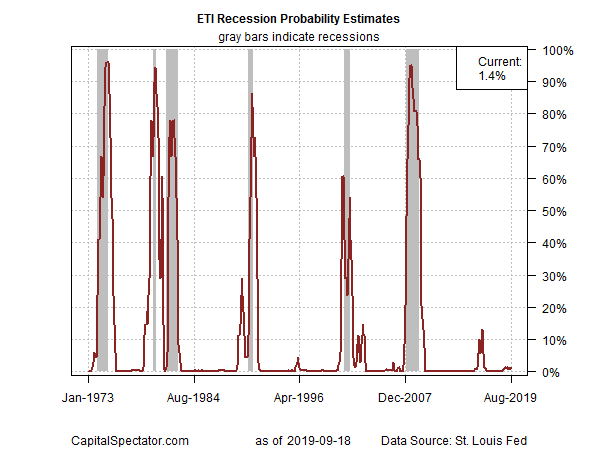

Despite the downshift in the trend, the data published to date for ETI continues to show that recession risk remains low, based on numbers published so far. Translating the index’s historical values into recession-risk probabilities with a probit model points to low business-cycle risk for the U.S. through last month. Analysis through this lens indicates that the odds remain virtually nil — roughly 1% — that NBER will declare August as the start of a new recession. Note, too, that a probit-model reading of EMI (not shown) also shows a low probability (7%) that the economy was contracting last month.

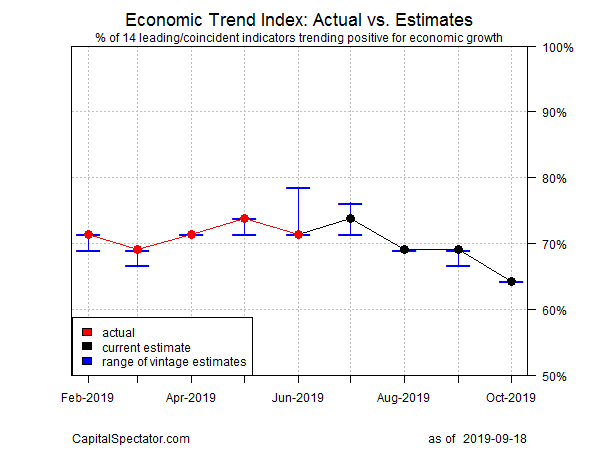

Turning to the near-term outlook, consider how ETI may evolve as new data is published. One way to project values for this index is with an econometric technique known as an autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) model, based on default calculations via the “forecast” package in R. The ARIMA model calculates the missing data points for each indicator for each month — in this case through October 2019. (Note that June 2019 is currently the latest month with a complete set of published data for ETI.) Based on today’s projections, ETI is expected to tick lower for a second month in October, delivering a mildly stronger warning that the trend remains on track to weaken further in the final months of the year.

Forecasts are always suspect, but recent projections of ETI for the near-term future have proven to be reliable guesstimates vs. the full set of published numbers that followed. That’s not surprising, given ETI’s design to capture the broad trend based across multiple indicators. Predicting individual components in isolation, by contrast, is subject to greater uncertainty. The assumption here is that while any one forecast for a given indicator will likely be wrong, the errors may cancel out to some degree by aggregating a broad set of predictions. That’s a reasonable view, based on the generally accurate historical record for the ETI forecasts in recent years.

The current projections (the four black dots in the chart immediately above) suggest that the economy will continue to expand through next month, albeit at a slowing pace. The chart also shows the range of vintage ETI projections published in previous months (blue bars), which you can compare with the actual data (red dots) that followed, based on current numbers.