It’s been a rough year for big IPOs. Lyft (NASDAQ:LYFT) is down almost 40% from its IPO price. Uber (NYSE:UBER) is down 30% and the vast majority of its early investors are underwater. Most recently, WeWork’s pre-IPO process flopped so badly that it ultimately postponed its public offering indefinitely.

The disaster that was the WeWork IPO seems like a tipping point for the market. In the past, investors have bought high-profile IPOs despite mountains of red flags. Now, public-market investors seem to have awoken to the risks of buying into certain offerings. They’ve realized they have the power to walk away from overpriced companies with conflicted corporate governance.

While this tipping point represents a positive shift in the market, it does not eliminate the risk that investors face from upcoming IPOs. Investors should expect unicorns and their backers – i.e. Wall Street and funds like SoftBank – to become even more desperate and creative as they try to offload their risk onto the public. The IPO market is in the Danger Zone.

The Problem With Having Too Much Money

Over the past decade, private equity investors seemed to have more capital than they knew what to do with. The rise of massive venture funds like the $100 billion SoftBank Vision fund – backed by Saudi Arabia – combined with an extended stretch of ultra-low interest rates, which created a market with more capital than profitable investment opportunities.

As a result, the traditional power dynamic between startups and investors inverted. Rather than startups competing to attract capital, venture capitalists competed to fund startups. In practice, that meant funding a startup’s losses, ignoring sound governance practices and giving them increasingly absurd valuations.

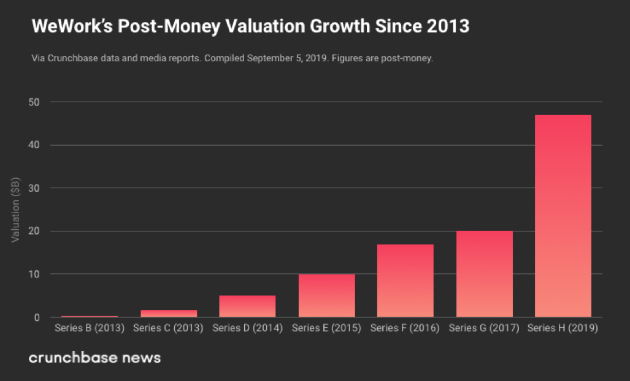

Take the example of WeWork. When the company first filed to go public, insiders hoped its IPO valuation would be near its last private funding valuation, $47 billion. Goldman Sachs (NYSE:GS) privately told people close to WeWork that its valuation could rise to $65 billion after going public. However, as Figure 1 shows, that private valuation was never tied to anything tangible. The company was valued much lower until 2017, when SoftBank got involved with its Series G funding round. Since then, SoftBank has led every subsequent round of funding for WeWork, pushing the valuation of the company ever-higher.

Sources: Crunchbase

This dynamic doesn’t reflect efficient market activity; it’s a product of the private market lacking any independent estimates of value. WeWork wanted a higher valuation so that former CEO Adam Neumann and other insiders could cash out at the highest price, while SoftBank got to mark up the value of its investment, record a gain and deploy some of the billions of dollars of capital on which its investors expect a decent return. There does not appear to be any appreciation for risk of bidding up the price of unicorns too high. Too often, the big private equity investors are only bidding against themselves when pricing the later rounds of capital for their unicorns.

The Private Equity Curse

At some point, this party ends because no one has limitless capital to fund a perpetually money-losing business with highly conflicted corporate governance.

Most people don't realize that the party ended a long time ago for one of private equity’s most important customers: publicly traded companies. Have you noticed how few of the private market unicorns have been purchased by their most natural buyers?

Executives at public companies have commented on how much more cheaply they can internally develop technology or offerings put forth by overpriced private firms. For example, TD Ameritrade Institutional CEO, Tom Nally, said in his interview with Barry Ritholtz earlier this year: “we thought it would cost about $5mm to build robo-advisor tech, so buying one for $100 million looks like a really bad decision.”

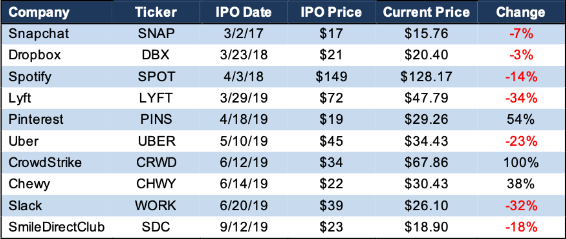

We believe the same thinking applied to many of the natural acquirers of the firms in Figure 2.

Consequently, as much as bidding up the value of the unicorns to dizzying heights drove private equity returns higher on paper in the near term, we think this profligate allocation of capital could ultimately crush many of those same firms.

Don’t Bail Out Reckless Private Equity Investors

Wall Street has managed to bail out the big private equity investors by offloading these overpriced and poorly run companies on to pubic markets, e.g. Uber (NYSE:UBER) and Lyft (NASDAQ:LYFT). Now, however, it appears pubic investors are – in the words of Twisted Sister – 'not gonna to take it anymore.'

To understand why investors finally managed to stand up for themselves with WeWork, look no further than Figure 2, which shows the performance of all the IPOs we’ve covered since 2017 with a market cap of $5 billion or greater. Seven out of ten have delivered negative returns and the largest companies on the list – Uber, Lyft and Slack (NYSE:WORK) – have also been the worst performers. Meanwhile, the S&P 500 is up 26% since SNAP’s IPO and up 20% so far in 2019.

Sources: New Constructs, LLC and company filings

The more the private market bids these companies up, subsidizes their losses and allows them to entrench founders at the expense of investors, the more difficult it becomes for these companies to deliver long-term returns for public investors.

Figure 2 also shows that the rate of unicorn IPOs has increased so far in 2019. This trend is no coincidence. Companies know that the window to IPO at such unrealistic valuations is closing and they’re all desperate to cash out as soon as they can.

Don’t Believe In Unicorns – Especially The Ones Sold By Wall Street

Investors may have succeeded in imposing some degree of rationality on the IPO market, but no one should be taking a victory lap just yet. Insiders and early investors at companies like WeWork are desperate for the exit of an IPO and they will continue to try to trick the public market into ignoring the red flags and risks in these investments.

Remember that WeWork tried to placate investors by “reforming” its corporate governance. These “reforms” included:

- Lowering the voting rights of the Class B and C shares held by then CEO Adam Neumann and other insiders from 20 votes per share to 10 votes per share

- Eliminating the clause that allowed Neumann’s wife, Rebekah, to play a key role in picking his successor

- Clawing back a $5.9 million payment to Neumann for the rights to the “We” trademark

Notably, those reforms would have enabled Neumann to retain complete control over the company and have the ability to engage in conflicted self-dealing after an IPO.

Investors shouldn’t fall for these phony changes. They should continue to demand real corporate governance reform, along with a clear path to profitability, from WeWork and any subsequent IPOs before even considering investing.

Disclosure: David Trainer, Kyle Guske II, and Sam McBride receive no compensation to write about any specific stock, style, or theme.