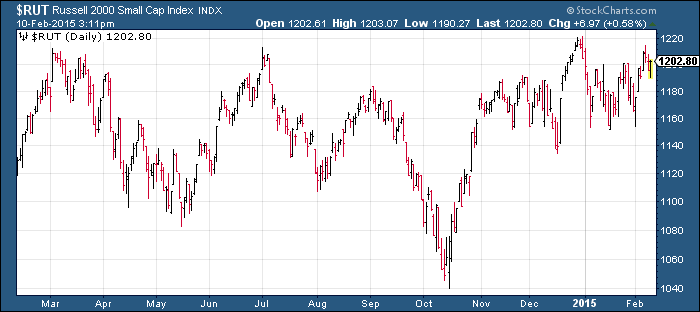

Investors are starting to feel numb by the lack of action in the broad market. Since December, the Dow Jones 30 and S&P 500 have settled into sideways trading ranges. The NYSE Composite (NYA) has been range-bound since last summer while the Russell 2000 (RUT) has been stuck in a lateral ranges for the past year. While trading ranges don’t necessarily result in the loss of capital, its effect on the minds of market participants tend to be significant. Trading ranges are frustrating. When trading ranges become established over a period of months the effects upon investor and mass psychology can even be devastating.

Consider that some of the most devastating social, political and military revolutions in history have occurred during prolonged periods of stagnation in both the economy and the equity market of the countries concerned. Human nature is dynamic and demands continual movement – whether in the form of progress or even regress. A long period of stagnation where neither progress nor regress is seen has a profound impact on the human psyche in the aggregate and can lead to psychosis if the stagnation continues for very long.

There is also the effect of the trading range to consider upon the mind of the individual. The celebrated stock trader Jessie Livermore is a case in point. After making a fortune selling short the stock market prior to the 1929 crash, he found himself at the mercy of the dull market conditions of the late ‘30s and early ‘40s and was unable to make his accustomed living from the market. He ended his life by blowing his brains out in a hotel coat closet in 1940.

Trading ranges also tend to be characterized by increased volatility. It’s easy to be fooled by the periods of increasing market volatility during the times when stocks are visiting the lower end of the trading range. Many (falsely) assume that the volatility spikes mean that the market is primed for a bear market. But periodic volatility spikes are part and parcel of any drawn out sideways movement in the major indices and nothing can be inferred by the temporary rallies in the Volatility Index.

It’s certainly understandable that investors, particularly small-cap investors, are feeling frustrated right now. After all, they’ve had to sit through more than a year of seeing their portfolios going virtually nowhere, if the Russell 2000 chart is any indication. It’s no wonder that active participation among retail traders has dwindled in the last several months.

Trading ranges serve a distinctive purpose, however, and they tend to be beneficial for the longer-term health of the stock market. Sideways trading ranges can either represent distribution (i.e. informed selling) or else accumulation (buying). More often than not, they represent a period of consolidation for a bull market that has over-exerted itself and needs rest. Lateral trading ranges typically serve as an intermission before the next phase of the bull market. As a rule, the longer the duration of the range, the more powerful the subsequent rally tends to be.

A good example of a trading range year, which gave way to a solid breakout performance for stocks occurred 10 years ago. Below is a chart of the Dow 30 index. Note the overall lateral trading pattern for much of that year.

Here is how the Dow resolved that range in 2006.

This is not to say that stocks will spend most of 2015 in a sideways trading range. As we talked about in the 2015 forecast edition, there are several likely inflection points this year for tradable trends – possibly lasting 2-3 months at a time. Another point worth mentioning: unlike in 2005, the longer-term yearly cycles are up, not down.

This brings us to the ultimate question: when will the current trading range period for the stock market finally end? That question is very much an open one for which the market hasn’t yet provided an answer. However, the indicators suggest that a breakout attempt above the trading range ceiling will likely be made in this quarter. Moreover, the odds strongly favor of an upside resolution to the lateral trading range by mid-year by virtue of this being: a.) an up year in the alternate 2-year cycle; b.) a Year Five Phenomenon year; and c.) a year when the Kress yearly cycles all kick in to the upside.