Over the last couple of week’s (see here and here), I have been discussing the value of Shiller’s CAPE ratio. The Cyclically Adjusted P/E ratio, or CAPE, is often maligned by the media as “useless” and “outdated” because despite the fact the ratio is currently registering the second highest level of valuation is history, the markets haven’t crashed yet. Of course, the key word is…YET.

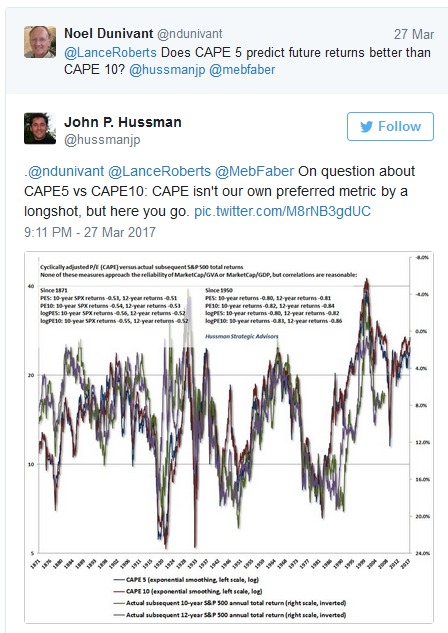

In the second article, I shorted the length of the CAPE ratio to make it more sensitive to price movements which sparked a good discussion on Twitter about forward return analysis using a shortened smoothing period. Leave it to my friend John Hussman to do the heavy lifting:

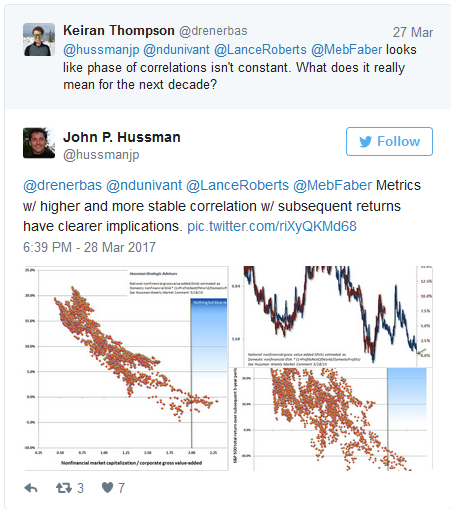

Of course, the obvious question is what are his favorite metrics? Here you go.

Within all of this is a simple point. No matter how you cut it, slice it, dice it, twist it, abuse it, or torture it – valuations matter in the long run.

But therein lies the problem, valuations are NOT, and never have been, a market timing tool. It is about the value you pay for something today and the return you will receive in the future, and a point that Research Affiliates recently took a very interesting approach to in a recent report:

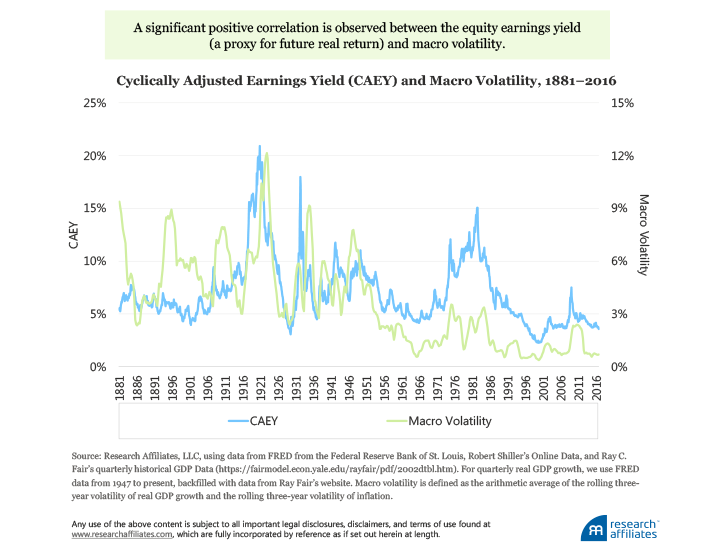

Academics have suggested various reasons for sustained higher equity valuations, from the microstructure benefits of improved participation and lower transaction costs to the macroeconomic benefits of larger profit shares. We examine the explanation put forward by Lettau, Ludvigson, and Wachter (2008) that rising valuations are propelled by the large reduction of macroeconomic risk in the US economy. Their intuition is simple—investors require lower returns from equity markets when the aggregate volatility of the economy is lower. It should come as no surprise that investors are glad to pay a higher price and accept a lower return for investing in a stock market that delivers less uncertainty.

Today’s economy is drastically different from just a few decades ago, and radically different from a century ago. Judging from the volatility of two major macroeconomic variables—real output growth and inflation—it has changed for the better. From the days before the US Federal Reserve Bank until today, the annual volatility of the economy has tumbled about 80%.

When we plot the measure of macro volatility with the inverse of a very popular valuation metric, Robert Shiller’s cyclically adjusted price/earnings ratio (CAPE), we find an intriguing and significant positive correlation between expected real equity returns and the aggregate volatility of the economy. Under the restrictive assumption that prices are fair and an appropriate return on retained profits, we assert that earnings yields are an appropriate proxy for an equity market’s future real return. For clarity, we name the inverse of the CAPE, an earnings yield, the cyclically adjusted earnings yield (CAEY).

Research Affiliates makes some very interesting points and the entire paper is worth reading. However, I was most interested in the concept of the Cyclically Adjusted Earnings Yield (CAEY) ratio and its relationship to forward real returns in the market.

While the statement that lower valuations, inflation, and lower volatility are supportive of higher valuations is true, there have also been other issues as well as I addressed last week:

- Beginning in 2009, FASB Rule 157 was “temporarily” repealed in order to allow banks to “value” illiquid assets, such as real estate or mortgage-backed securities, at levels they felt were more appropriate rather than on the last actual “sale price” of a similar asset. This was done to keep banks solvent at the time as they were being forced to write down billions of dollars of assets on their books. This boosted banks profitability and made earnings appear higher than they may have been otherwise. The ‘repeal” of Rule 157 is still in effect today, and the subsequent “mark-to-myth” accounting rule is still inflating earnings.

- The heavy use of off-balance sheet vehicles to suppress corporate debt and leverage levels and boost earnings is also a relatively new distortion.

- Extensive cost-cutting, productivity enhancements, off-shoring of labor, etc. are all being heavily employed to boost earnings in a relatively weak revenue growth environment. I addressed this issue specifically in this past weekend’s newsletter.

- And, of course, the massive global Central Bank interventions which have provided the financial “put” for markets over the last eight years.

Furthermore, the point suggesting investors are willing to accept lower returns in exchange for lower volatility is intriguing.

While academically speaking I certainly understand the point, I am not so sure the average market participant does who is still being told to bank on 6-8% annualized rates of return for retirement planning purposes.

However, this brings us to the inverse of the P/E ratio or Earnings Yield. The earnings yield has often been used by Wall Street analysts to justify higher valuations in low interest rate environment since the “yield on stocks” is higher than the “yield on risk free-assets,” namely U.S. Treasury bonds.

This is a very faulty analysis for the following reason. When you own a U.S. Treasury you receive two things – the interest payment stream and the return of the principal investment at maturity. Conversely, with a stock you DO NOT receive an “earnings yield” and there is no promise of repayment in the future. Stocks are all risk and U.S. Treasuries are considered a “risk-free” investment.

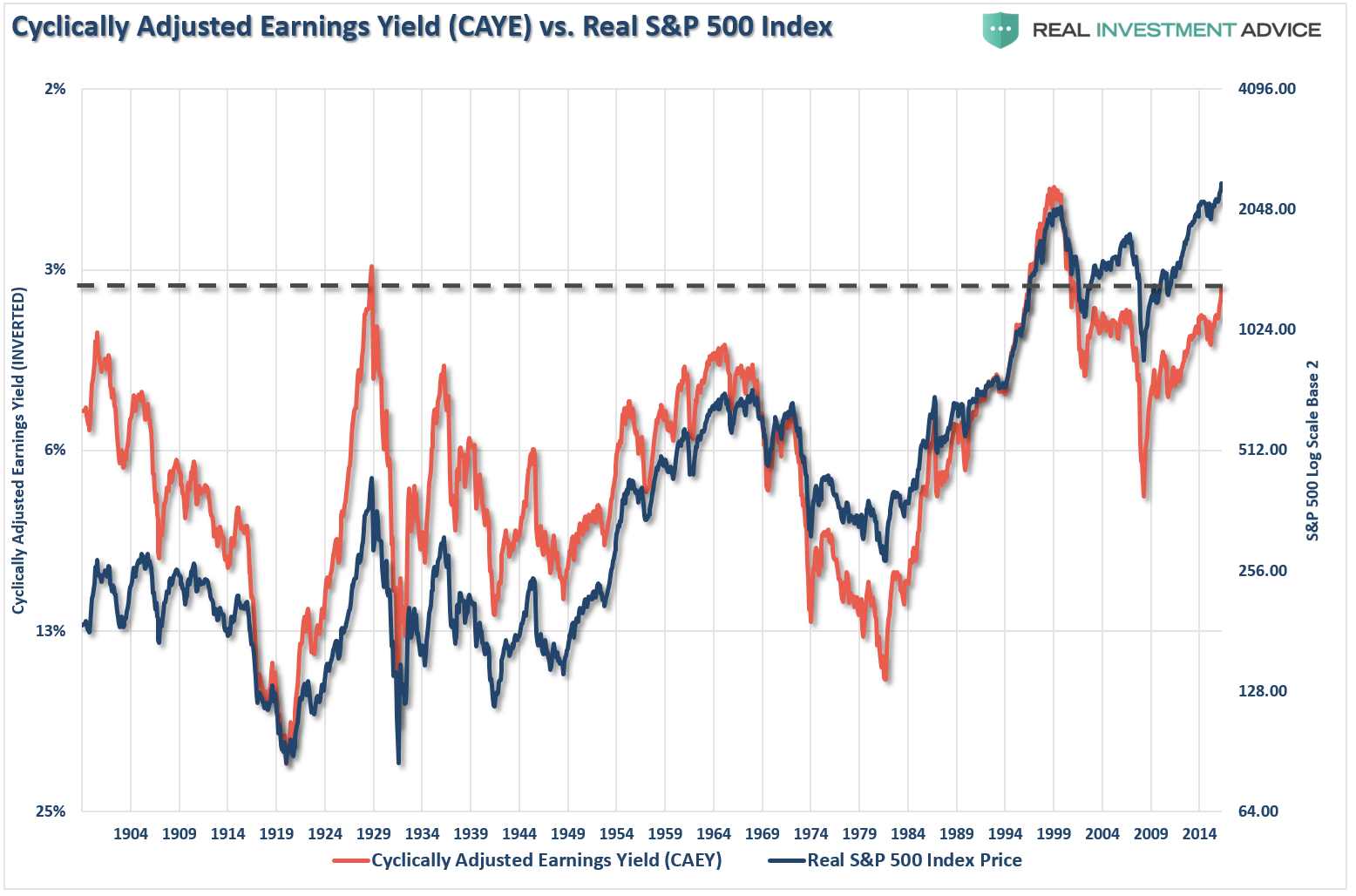

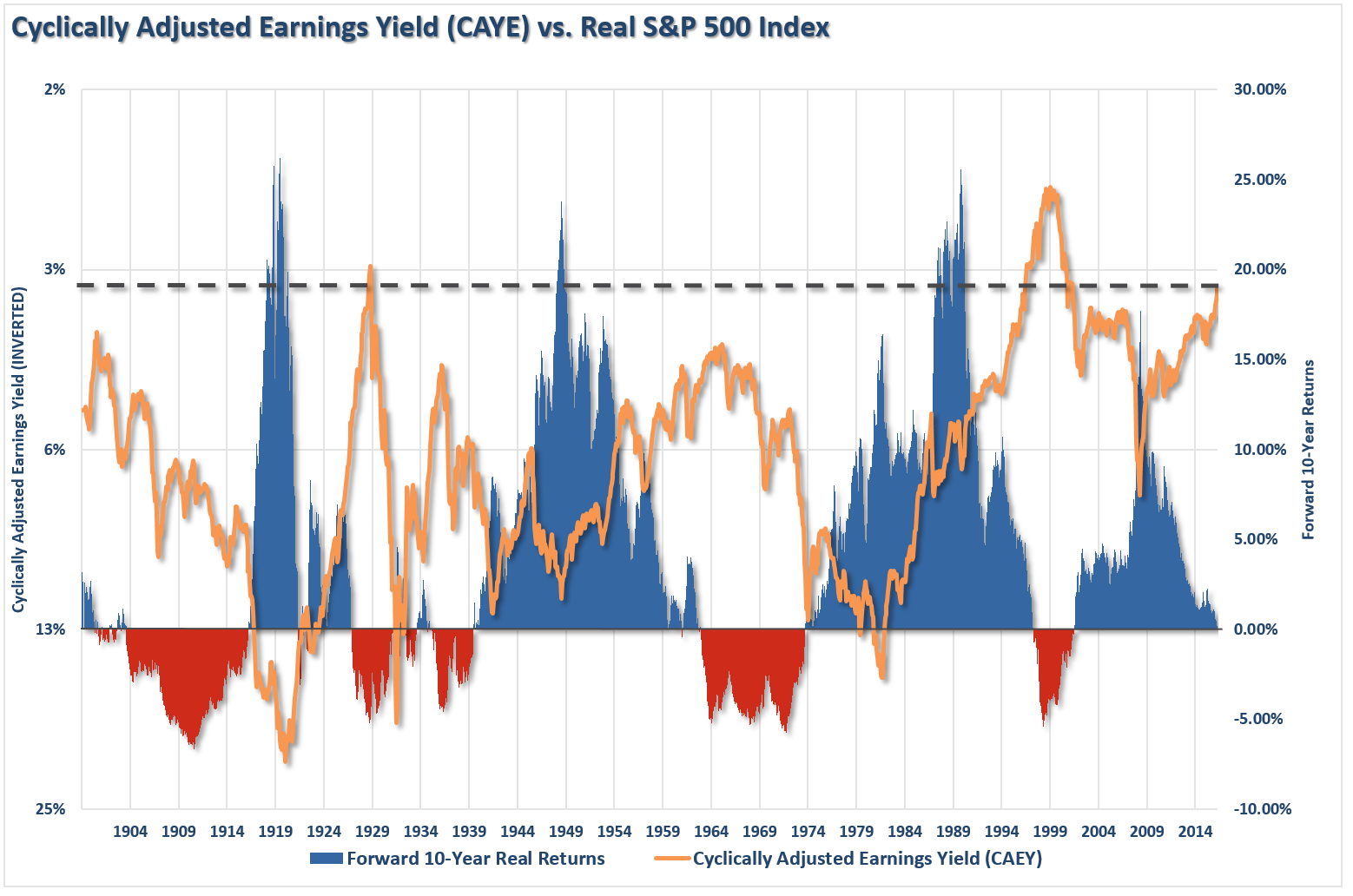

The chart below, which uses Shiller’s data set, shows the 10-year Cyclically Adjusted Earnings Yield. I have INVERTED the earnings yield to more clearly show periods of over and under-valuations.

With the CAEY currently at the 3rd lowest level in the history of the financial markets, it should not be surprising to expect lower returns in the future. Of course, lower returns is exactly what Research Affiliates suggests you will accept in exchange for lower volatility.

Right?

The chart below shows the CAEY as compared to 10-year forward real returns (capital appreciation only).

Not surprisingly, when the CAEY ratio has reached such low levels previously, forward returns were not only low, but negative. Currently, with the earnings yield nearing 3%, forward 10-year returns are going to start approaching zero and potentially go negative in the years ahead.

Of course, such declines in returns will, as they always have, coincided with a recession and fairly nasty mean-reverting event which has historically consisted of declines in asset prices of 30% on average.

But hey, you are okay with that, right?

I mean, after all, you did agree to lower returns when you bought into overvalued equity markets in exchange for lower volatility.

For investors, planning for future wealth and security relies on reasonable assumptions about future expected returns. No matter how you do the math, returns over the next decade, which can be forecasted with a fairly high level of predictability, will be low.

Long-term trend of mean reversion implies lower-than-average earnings per share in the future due to a decline in productivity. So, we estimate that EPS growth over the next decade is likely to be at about 1%. In reality, the return for the S&P 500 over the next 10 years could be somewhere between zero to low single digits.” – Chris Brightman, Research Affiliates

Remember, while valuations are not a market timing tool in the short-run. Using fundamental measures to predict returns 12-months out is a fruitless endeavor. However, over the long-term, the math is always the same:

The price you pay today is extremely indicative of the return you will receive in the future.

Just something to consider.