If the Federal Reserve raises the federal funds rate much further, it risks triggering a recession. That’s not my opinion; rather, it is the opinion of Neel Kashkari, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis.

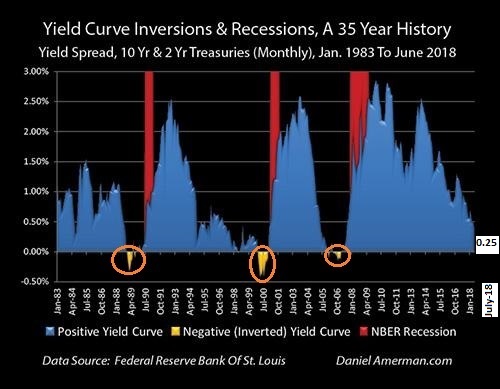

Kashkari’s thesis? When shorter-term rates rise above longer-term ones – a phenomenon known as yield curve inversion – the financial markets are anticipating an economic slowdown in the near future.

Additionally, Kashkari does not care why longer-term Treasury yields are flat or falling (e.g., trade wars, excess savings across the globe, etc.). He simply suggests that if the U.S. Fed stays the course on its rate hike intentions, then the central bank will cause the yield curve to invert and jeopardize the country’s economy.

Several of Kashkari’s colleagues share his concerns. For example, St. Louse Fed chief James Bullard acknowledged the historical reliability of the inverted yield curve as a warning and expressed a belief that this time would not be different. Similarly, Atlanta Fed President Raphael Bostic stated that investor belief in the indicator could bring about a recession through a self-fulfilling prophecy.

In complete contrast, Fed Chair Jerome Powell seems entirely unfazed by the high probability that his actions will push shorter-term rates above longer-term counterparts. In recent testimony before Congress, he downplayed the relevance of the indication that forewarned all of the previous seven recessions.

“What really matters is what the neutral rate of interest is,” he stated. The neutral rate, however, is a hypothetical construct. And the Fed has struggled in the past to identify the interest rate level that neither stimulates economic growth nor decelerates it.

Consider the 1998-2000 rate hiking campaign. The Fed raised the federal fund rates too far, inverted the yield curve, watched job growth fall off a cliff, and then scrambled to lower rates in an effort to revive a moribund economic environment. Or consider the 2004-2006 rate hiking activity. Once again, the Fed raised the federal funds rate too far, inverted the yield curve, watched job losses slam millions of people, and then rushed to minimize the damage.

Keep in mind, by keeping interest rates too low for too long in previous central banking experiments, the Fed had fueled speculative asset bubbles. Dot-com and tech in the 1990s. Real estate in the 2000s. So when it came time to seek the so-called neutral rate, and perhaps curb some of the financial excesses, the inevitable boom times turned to bust.

Critically, the Federal Reserve was not able to arrest the development of severe bear markets in stock assets, even after they shifted from tightening policies or “neutral policies” back to stimulative policies. In both of the last two “about-faces” by the Fed, the S&P 500 tumbled by more than 50%. Stock prices went on sale at 50% discounts not once, but twice!

Perhaps ironically, if the Fed wants to keep raising overnight lending rates without inverting the yield curve, they can easily do so. For one thing, it can stop its price agnostic ingestion of 20% of the supply of all newly issued 10-year Treasuries and 30-year Treasuries. The Fed could let the supply of Treasuries build. Investors from pension funds to foreign participants to asset managers would acquire the debt, but at much higher yields. Voilá… steeper yield curve.

By the same token, the Fed could swap some of its longer-term bonds for shorter-term maturities (a.k.a. “reverse twist”). Shorter-term bond yields would fall. Longer-term bond yields would rise. Bingo… the yield curve would steepen.

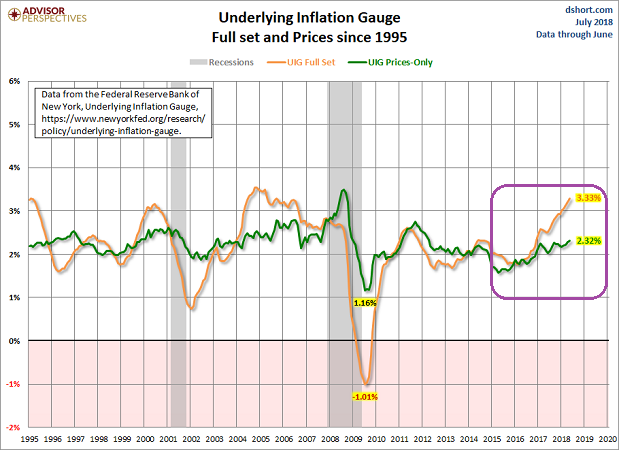

Clearly, then, the Federal Reserve does not see itself in the business of inversion avoidance nor steepening encouragement. Based on the mandates of price stability and full employment, some Fed committee members see inflation as a threat to price stability. They may also believe we are already at full employment, and therefore, the risks of inflationary pressures building are giving them the fortitude to stay on the rate increasing path.

Kashkari’s camp would have a tough time denying that inflation is rising. Every measure is moving upward, from core CPI (2.3%) to PCE (2.3%) to core PCE (2%).

Yet, an overheating economy is a different beast. Kashkari explains that if the markets were expecting higher inflation or stronger inflation-adjusted economic growth in the future, we would see that evidence in long-term bond yields. In contrast, he believes the 2.85% level for the 10-year is a sign that inflation is not about to take off, nor is inflation-adjusted economic growth set to rocket ahead.

Obviously, Kashkari and other Fed colleagues understand that the central bank could stop purchasing 20% of newly issued long-term bonds and/or conduct a “reverse twist” to steepen the yield curve. So why does the debate at the Fed on rate policy as well as balance sheet reduction land squarely at the Shakesperian doorstep of “To invert or not to invert?”

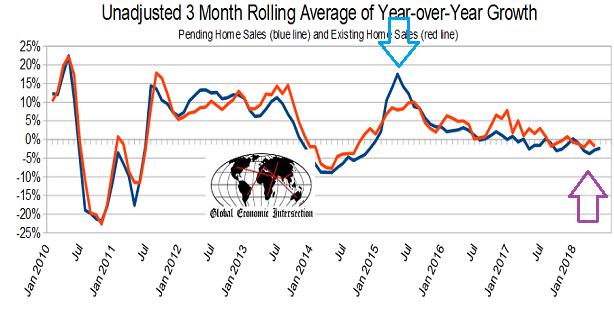

My sense is that there is less concern at the Fed about yield curve inversion than there is about significantly higher borrowing costs in real estate. A 10-year that is tethered to a 3% level (2.75%-3.25%) may be the upper limit for the current business cycle, regardless of what the overnight lending rate/federal funds rate is. After all, potential buyers are already struggling with home price increases that outpace wage gains as well as mortgage rates that are meaningfully higher from just a few years earlier.

So if Fed folks believe it is more prudent to aid in the anchoring of longer-term interest rates, perhaps by acquiring a large percentage of the bond supply, the institution is left with decisions regarding its mandates; that is, what should it do to ensure modest inflation and maintaining full employment? The answer is to prepare its arsenal to combat the next recession whenever it may occur.

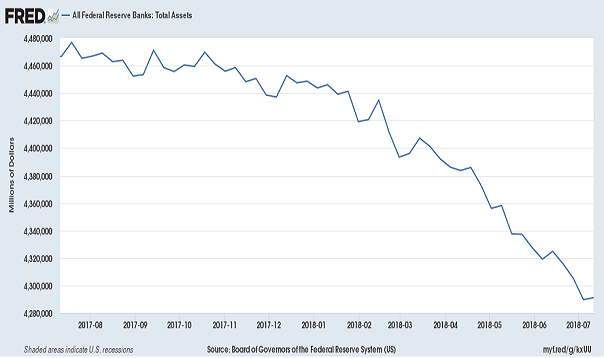

How can the Fed restock its arsenal? By raising the overnight lending rate and by reducing its balance sheet… even if yield curve inversion comes to fruition. Paradoxically, the higher the overnight lending rate and the lower the Fed’s balance sheet, the more ammunition The Fed would have to jump-start the economy by utilizing zero percent interest rate policy (ZIRP), negative interest rate policy (NIRP) and quantitative easing (QE)/balance sheet expansion in the future.

For now, though, the pace of Fed tightening continues. And the pace of Fed quantitative tightening via balance sheet reduction quickens.

Neel Kashkari might not like it. He might prefer to let inflation prove that its running hot before doing anything about it. What’s more, he has been one of the most vocal proponents of keeping rates as low as possible for as long as possible. Heck, we might still be sitting at 0% on the federal funds rate instead of the 1.75%-2.0% range if Kashkari sat in the chairperson’s seat.

Then again, Kashkari does not see the speculative asset bubbles across stocks, bonds and real estate, let alone the problems associated with having kept rates “too low for too long.” In contrast, however, many of his colleagues are keenly aware of the financial excess that they’ve helped to orchestrate.

It follows that Fed Chair Powell may deem quantitative tightening and traditional tightening on the short end of the curve more palatable than either: (a) intervening to steepen the yield curve or, (b) slowing or terminating the rate hike campaign. Rapid steepening could kill the credit cycle and its favorite beneficiary, real estate. Premature rate neutrality might lead to extreme malinvestment up and above what already exists.

Conversely, the third choice of inverting the yield curve in late 2018 may be a hard place for the Fed to be, as the inversion may pose recessionary risks that occur 6-24 months out. Nevertheless, of all the risks that Powell is forced to take, it may be the “least-worst” alternative.

How might this be affecting risk assets like stocks? A great deal of sideways movement so far.

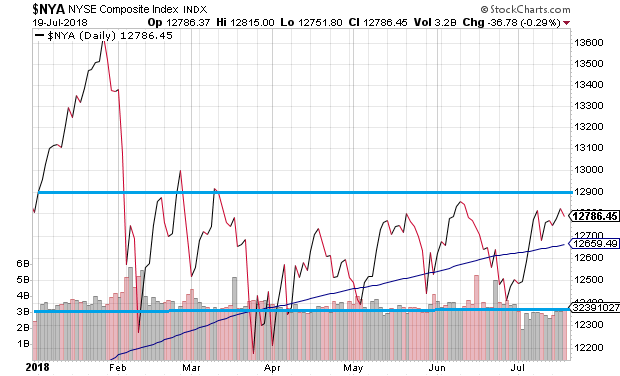

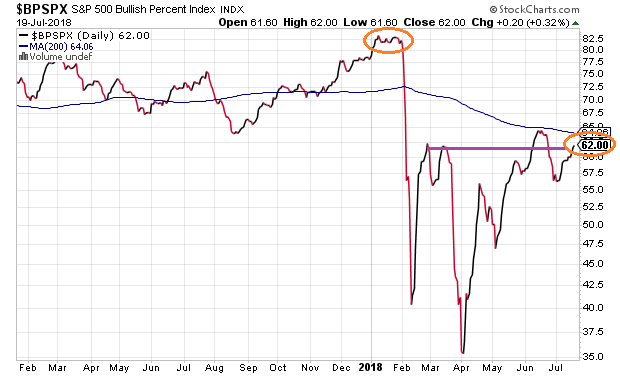

It’s one thing to take note of the NASDAQ Composite’s unrepentant strength and the S&P 500’s 4.9% gains in 2018. On the flip side, the S&P 500 has still yet to eclipse its January peak from nearly six months ago. Meanwhile, the broader NYSE Composite Index has been range-bound since the January-February correction.

Keep in mind, the S&P 500’s year-to-date gains are primarily a function of a handful of FANG-plus stocks. The rest of the market? A whole lot less bullish. And that means, you may not have the “margin of safety” that you think you have in a single indexing asset like the SPDR S&P 500 ETF (SPY).

Disclosure Statement: ETF Expert is a web log (“blog”) that makes the world of ETFs easier to understand. Gary Gordon, MS, CFP is the president of Pacific Park Financial, Inc., a Registered Investment Adviser with the SEC. Gary Gordon, Pacific Park Financial, Inc., and/or its clients may hold positions in the ETFs, mutual funds, and/or any investment asset mentioned above. The commentary does not constitute individualized investment advice. The opinions offered herein are not personalized recommendations to buy, sell or hold securities. At times, issuers of exchange-traded products compensate Pacific Park Financial, Inc. or its subsidiaries for advertising at the ETF Expert website. ETF Expert content is created independently of any advertising relationship.