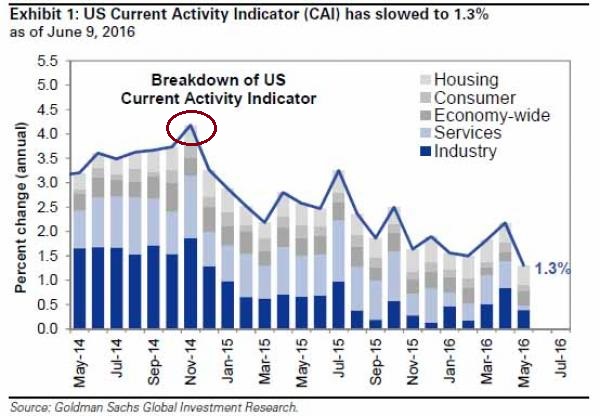

According to the Goldman Sachs Group's (NYSE:GS) Current Activity Indicator (CAI), economic well-being peaked in November of 2014. The erosion from 4.1% down to 1.3% over the last 18 months demonstrates just how vulnerable the U.S. economy currently is.

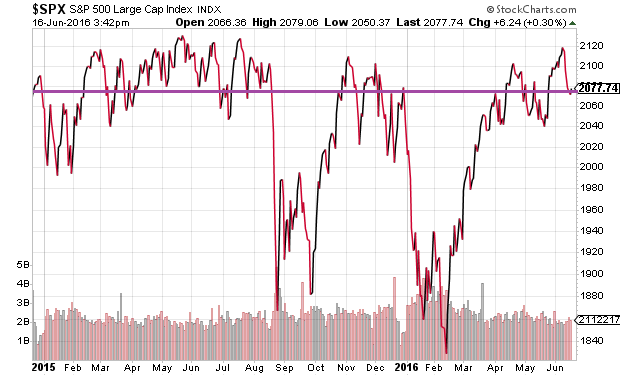

Not surprisingly, economic weakness has taken its toll on stock assets. The S&P 500 has not gained meaningful ground since the Fed officially stopped its bond purchases on December 18, 2014. What about small-cap stocks in the Russell 2000? A bit of depreciation over the year-and-a-half period.

One may be able to make the case that U.S. equities have been resilient. After all, they’ve recovered most of the ground lost in the August-September correction (2015) as well as the January-February sell-off (2016). What one is unable to do is claim that the economy itself has been able to bounce back from ongoing deterioration since the Fed began winding up its seven-year experiment with quantitative easing (QE).

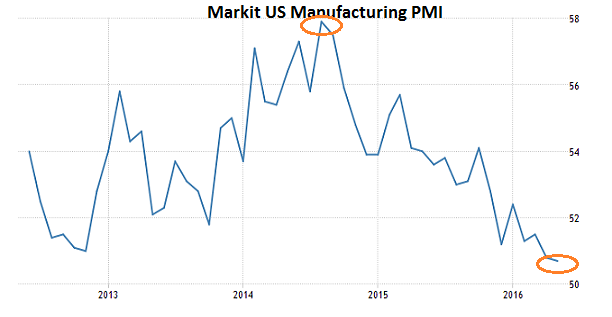

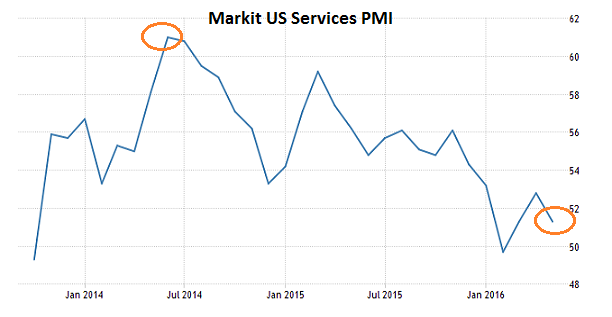

Consider the weakening services sector over the last two years. In June of 2014, the U.S. services sector had been firing on all cylinders. Today? With the Markit US Services PMI straddling the line between expansion and contraction, one is hard-pressed to describe the current environment as anything other than shaky.

Meanwhile, the manufacturing sector is fending off stagnation. The deterioration since the 3rd quarter of 2014 has been fast and furious.

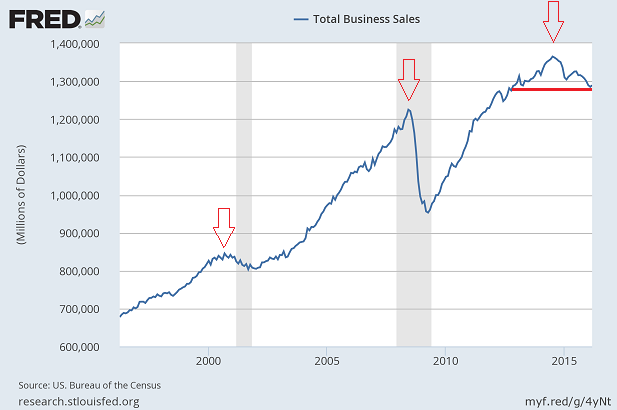

For those that have been following the retrenchment in both domestic and global economies, the evidence does not come as a surprise. The central bank of the United States slowly tapered its emergency level bond acquisitions throughout 2014, culminating in December. In that same time frame, service providers began selling less. Manufacturers began selling less. And total business sales have been evaporating since they peaked in the 3rd quarter of 2014.

The Ramifications Are Threefold:

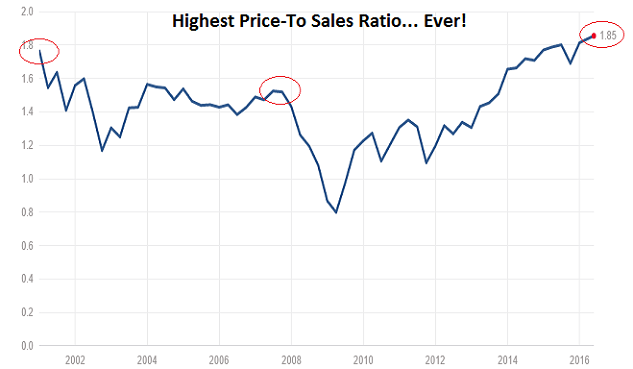

First, investors have begun to take notice of the reality that stock prices relative to sales (TTM P/S) are at their highest levels ever. On a price-to-revenue basis, in fact, stocks were cheaper during the dot-com euphoria days of 2000.

Second, investors have become more aware that corporate profits, not just corporate revenue, have been disintegrating since the Fed reined in its QE3 program in earnest. GAAP-based profits per share for the S&P 500 crested on 9/30/2014 at roughly $106. They have been dissipating ever since. Indeed, 3/30/2016 profits at $86.4 for the S&P 500 represents an 18.5% fall from grace. With the large-cap U.S. benchmark currently trading near 2075, it has become a fool's play to buy the big-name stocks that now command an astonishing price-to-earnings multiple of 24 (TTM P/E).

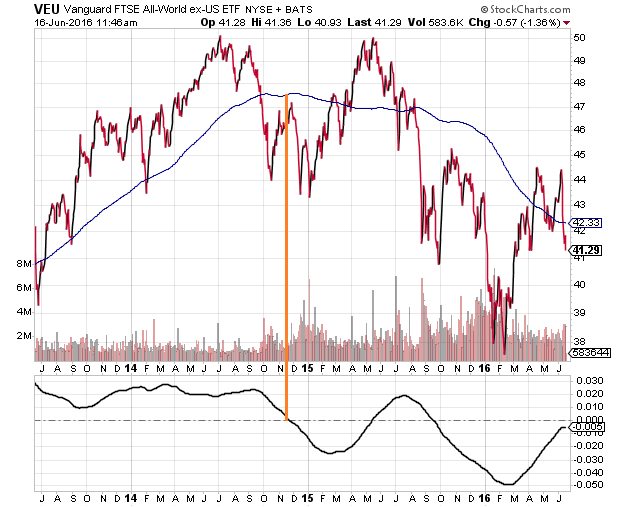

Third, absent more stimulus by the Federal Reserve, selling pressure may be particularly violent for foreign equities. The Vanguard FTSE All World ex US ETF (NYSE:VEU) highlights when the downtrend for foreign stocks began. Just as the Fed wrapped up QE3 in the 4th quarter of 2014, VEU's 200-day moving average began its downward slope.

Granted, foreign central banks like the ECB and BOJ have been spinning their QE wheels like crazy. The ECB’s electronic money printing to acquire government debt has pushed the German 10-year bund into negative territory, while ECB’s recent decision to buy corporate bonds and sovereign debt has sent yields on corporates tumbling. Not to be outdone, the BOJ has been acquiring stock ETFs as part of its quantitative easing activities. And yet, in spite of copious amounts of ECB and BOJ asset acquisitions, non-U.S. stocks are still hurting.

Janet Yellen and her Fed colleagues realize that maintaining a wealth effect stateside still requires economic stability abroad. It follows that, after initially implying (in late 2014) a series of rate hikes for 2015, Ms. Yellen pointed to global economic woes when resorting to a single rate hike in late December. After having initially implied a series of four hikes in 2016, the Fed now talks about a single bump higher at some point this year.

Really? Why would anyone believe what the Fed says it will do anymore?

According to Eric Balchunas at Bloomberg, investors are losing the faith. Specifically, ETF fund flows suggest that dollars are no longer flowing in and out of assets based on the Fed’s potential effect on interest rates. Rather, dollars are flowing in and out of ETFs due to fears of bearish stock implications.

To wit, the largest leveraged ETF for the better part of the last six years had been ProShares UltraShort 20+ Year Treasury (NYSE:TBT). Now it's the ProShares UltraShort S&P 500 ETF (NYSE:SDS). Similar “stock-proofing” can be seen with the SPDR Gold Trust (NYSE:GLD) taking in roughly double the next competing ETF – $10 billion this year alone. And then there's the $13 billion inflow to low-volatility ETFs, including favorites like iShares MSCI USA Minimum Volatility (NYSE:USMV) and iShares MSCI EAFE Minimum Volatility (NYSE:EFAV). Balchunas suggests that the desire to forgo some of the upside in hope of limiting downside is a clear indication of stock-market wariness.

There’s more. The exceptional year-to-date performance for the FTSE Multi-Asset Stock Hedge Index – the “MASH” Index I helped create – demonstrates the high demand for risk-off assets. The index holds currencies like the yen, precious metals such as gold along with longer-term sovereign debt like U.S. Treasuries.

In truth, the Federal Reserve is getting closer and closer to abandoning rate hikes entirely in 2016. From my vantage point, however, it will not be enough to bolster the economy or stock assets. The central bank of the United States may need to expand its balance sheet yet again. Members of the Open Market Committee (FOMC) may need to promise a fourth round of QE.

That’s not an endorsement for emergency-level stimulus or a QE4. On the contrary. It's a recognition of the unparalleled relationship between the Fed’s balance sheet and stock-price appreciation throughout the seven-plus years of stock bullishness.