Some investors transitioned from a “fear of missing out” (aka FOMO) at the beginning of the year to a worry that things are now “as good as it gets” – meaning that the market is in its last bullish move before the inevitable downturn kicks in. And now, escalating trade wars and a flattening yield curve have added to those fears. However, it appears to me that little has changed with the fundamentally strong outlook characterized by global economic growth, strong US corporate earnings, modest inflation, low real interest rates, a stable global banking system, and historic fiscal stimulus in the US (including both corporate tax cuts and deregulation). Moreover, the Fed may be sending signals of a slowing of rate hikes, while great strides have been made in reworking trade deals.

Many followers of Sabrient are wondering why our Baker’s Dozen portfolios – most of which had been performing quite well until mid-June – suddenly saw performance go south even though the broad market averages have managed to achieve new highs. Their concerns are understandable. However, if you look under the hood of the S&P 500, leadership over the past three months has not come from where you would expect in a robust economy. An escalation in trade wars (moving from posturing to reality) led industrial metals prices to collapse while investors suddenly shunned cyclical sectors in favor of defensive sectors in a “risk-off” rotation, along with some of the mega-cap momentum Tech names. This was not healthy behavior reflecting the fundamentally-strong economy and reasonable equity valuations.

But consensus forward estimates from the analyst community for most of the stocks in these cyclical sectors have not dropped, and in fact, guidance has generally improved as prices have fallen, making forward valuations much more attractive. Sabrient’s fundamentals-based GARP (growth at a reasonable price) model, which analyzes the forward estimates of the analyst community, still suggests solid tailwinds and an overweight in cyclical sectors. Thus, we expect that investor sentiment will eventually fall in line and we will see a “risk-on” rotation back into cyclicals as the market once again rewards stronger GARP qualities rather than just the momentum or defensive names. In other words, we think that now is the wrong time to exit our cyclicals-heavy Baker’s Dozen portfolios. I talk a lot more about this in today’s commentary.

Of course, risks abound. One involves divergent central bank monetary policies, with some continuing to ease while others (including the US and China) begin a gradual tightening process, and the enormous impact on currency exchange rates. Moreover, the gradual withdrawal of massive liquidity from the global economy is an unprecedented challenge rife with uncertainty. Another is the high levels of global debt (especially China) and escalating trade wars (most importantly with China). Because China is mentioned in every one of these major risk areas, I talk a lot more about China in today’s commentary.

In this periodic update, I provide a market commentary, offer my technical analysis of the S&P 500, review Sabrient’s latest fundamentals-based SectorCast rankings of the ten US business sectors, and serve up some actionable ETF trading ideas. In summary, our sector rankings now look even more strongly bullish, while the sector rotation model retains its bullish posture.

Market Commentary:

Impact of trade wars on Sabrient’s GARP portfolios:

First let me speak to recent market conditions, because investor sentiment is not as confident as the recent all-time highs make it seem. A strong 2017 carried over into January, led by the momentum factor and growth stocks, reflecting brimming business, consumer, and investor confidence in synchronized global economic growth and the massive potential presented by fiscal stimulus here at home. Most of Sabrient’s cyclicals-heavy portfolios thrived during this period. But then February brought about an overdue correction on fears of rising inflation and stock valuations getting ahead of themselves, and market behavior hasn’t been quite the same ever since, as trade war rhetoric has kept investors jittery and sector correlations rose from around 50% to roughly 80% (reflecting more in the way of risk-on/risk-off behavior).

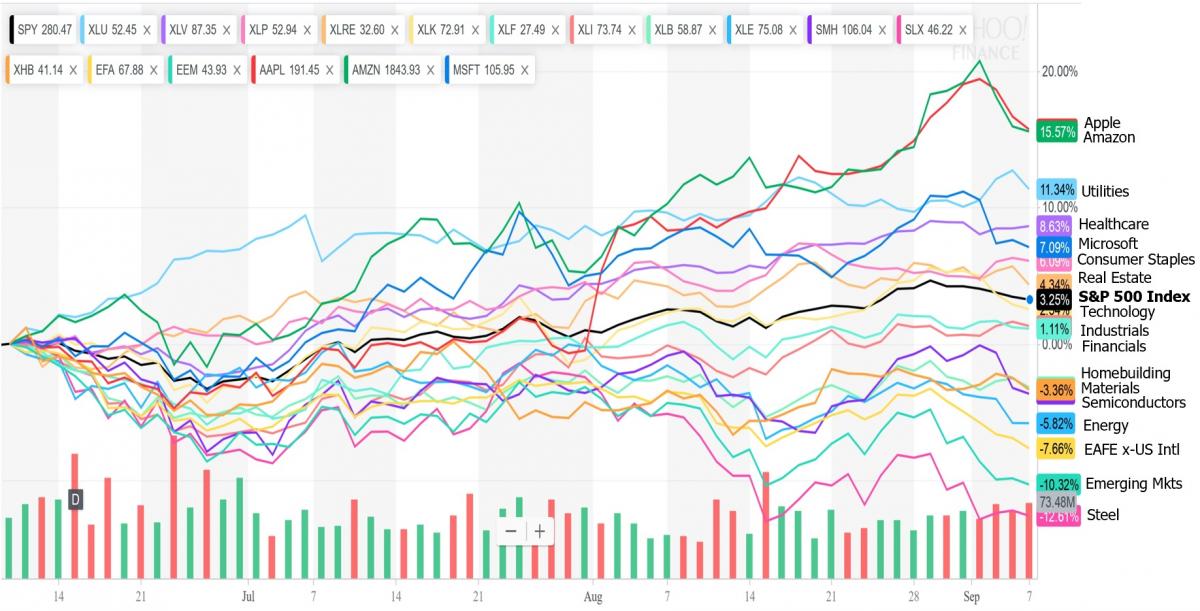

And then on June 11, the sudden escalation in trade wars (when President Trump announced a 25% tariff on $50 billion of Chinese imports) led investors to take profits in the cyclical sectors (e.g., Industrials, Materials, Steel, Homebuilding, Energy, Financials, Semiconductors) and rotate capital into the defensive and dividend-paying sectors (e.g., Utilities, Healthcare, Real Estate, Consumer Staples) and the low-volatility factor, along with a few mega-cap momentum Tech names that include the three largest holdings in the S&P 500: Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL), Microsoft (NASDAQ:MSFT), and Amazon (NASDAQ:AMZN). Notably, those three companies account for almost half of the S&P 500’s return since June 11, and two of them (AAPL and AMZN) recently reached $1 trillion market caps.

You can see the rotation since June 11 among various sector ETFs and mega-cap Techs in the chart below, as well as a similar risk-off divergence in the relative performance of international markets represented by the iShares MSCI EAFA ETF (EFA) and the iShares MSCI Emerging Markets ETF (NYSE:EEM):

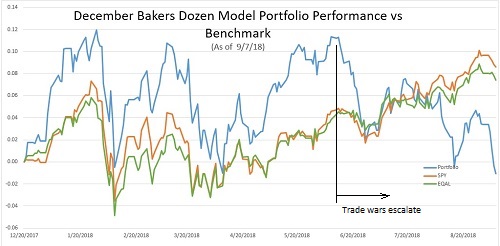

Meanwhile, Sabrient’s quantitative GARP model has pointed us toward the cyclical sectors, as you would expect in a robust economy. Our December Baker's Dozen launched late in December, so it can help serve to illustrate the 2018 YTD performance of our models, and you can see in the chart below the sudden performance downturn starting on June 11 coinciding with the escalation in trade wars. (Note: it shows gross price performance of our Model Portfolio, not the net return of the UIT portfolio that seeks to track it.)

If you believe that US and global economies are strong and growing, then cyclicals (and our portfolios) are likely only temporarily underperforming. But for now, our pronounced sector tilts away from the benchmark’s allocations have magnified the impact on relative performance. The S&P 500 benchmark has been able to hold up better (and even move to new highs) due to three key aspects: 1) a high (26%) sector allocation to the Technology sector, which our GARP model has not been favoring lately as much as it did in prior years; 2) persistent strength in mega-cap momentum names like AAPL, MSFT, AMZN, which are its 3 largest holdings; and 3) the ability to retain investment capital while temporarily rotating internally into defensive sectors like Utilities, Healthcare, Real Estate, and Consumer Staples.

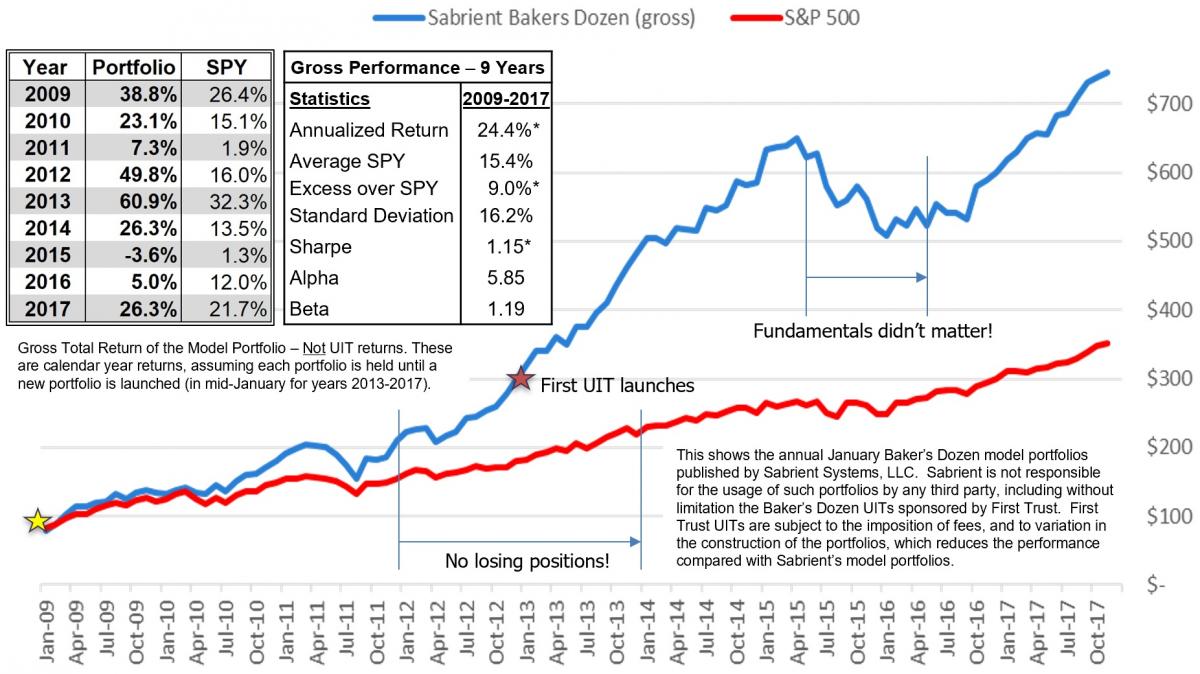

Sabrient’s concentrated Baker’s Dozen portfolios are designed to offer strong potential for alpha versus the broad market, but they also can display higher volatility – especially given sector tilts away from the benchmark. But this current performance divergence (extreme as it may be) certainly does not lead me to lose confidence in the long-term performance of Sabrient’s disciplined bottom-up process, which continues to be run by founder David Brown and the combined Sabrient/Gradient analyst team. History shows that when the market is rewarding fundamentals (rather than simply reacting to the news stream in risk-on/risk-off behavior), our GARP approach tends to work quite well. The chart below shows the long-term gross performance of our annual January Model Portfolio, 2009-2017, going into this year:

The main periods of underperformance were in 2H2011 and the 12-month timeframe 2H2015-1H2016, during which the market was news-driven rather than fundamentals-driven. You can find more information, including the specific holdings of each historical January portfolio, as well as the new monthly Baker’s Dozens, here.

Of course, if the sell-side analyst community were to slash estimates in the cyclical sectors due to a change in outlook, that would certainly impact our quant rankings. But that has not yet been the case, as the consensus forward estimates from the analyst community for most of the stocks in these cyclical sectors have not dropped, and in fact, guidance has generally improved as prices have fallen, making forward valuations much more attractive. And with fiscal stimulus boosting what I think is a mid-cycle economy that seems ready to finally ramp into a boom phase, cyclicals remain the place to be overweighted, according to our model.

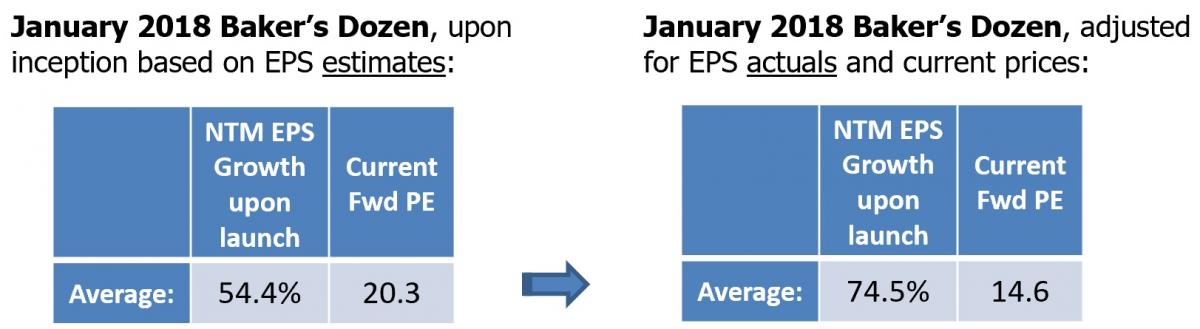

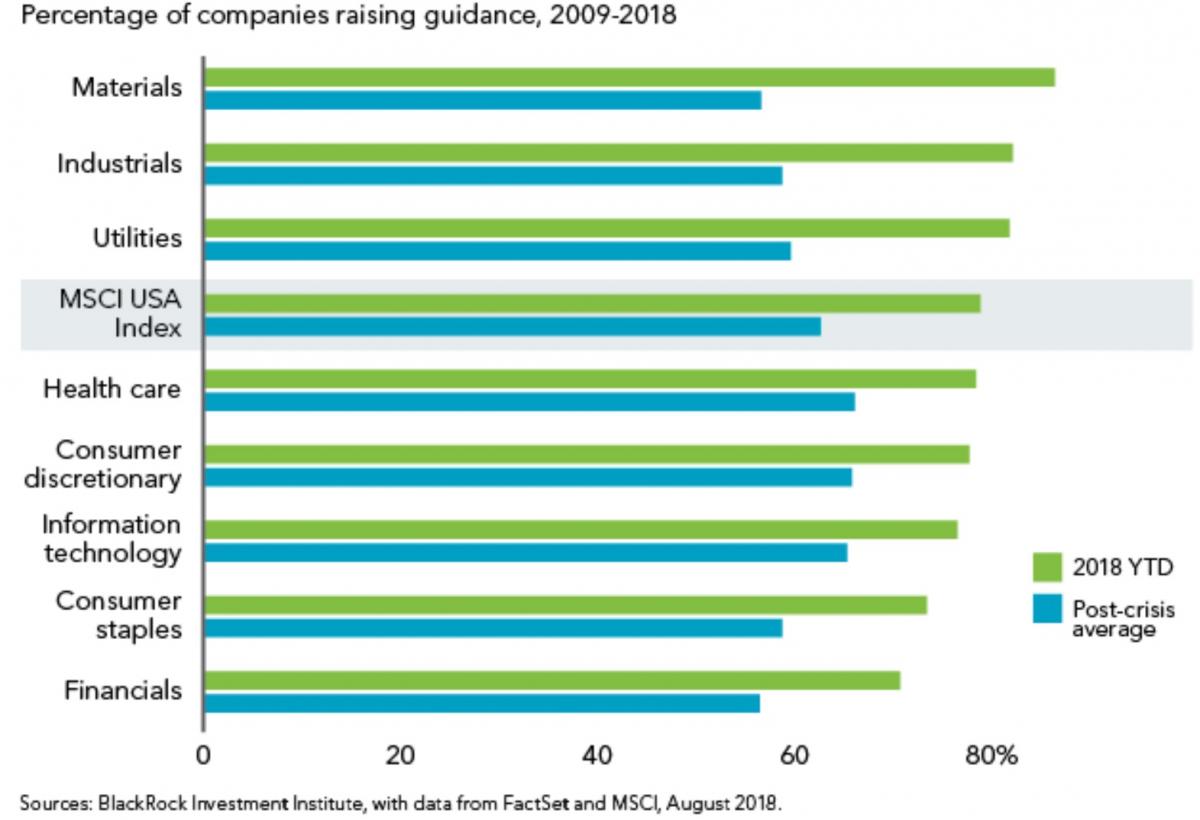

Indeed, the tables below show how much better the EPS growth for next 12 months (NTM) and forward P/E ratio are when we replace the original estimates for Q1 and Q2 with actual reported EPS numbers for the January Baker’s Dozen stocks, along with current prices. In addition, the second graphic published by BlackRock shows that Materials and Industrials companies have been raising guidance this year much more than the post-Financial Crisis average, despite the trade wars. Unless guidance suddenly weakens significantly and the analyst community slashes forward estimates, we fully expect these stocks to recover, as their numbers are just too good.

So, forward valuations for our Baker’s Dozen stocks appear to be much more attractive. And with fiscal stimulus boosting what I consider to be a mid-cycle economy that finally seems ready to ramp into a long-awaited boom phase, cyclicals remain the place to be overweighted, according to our model. We have great optimism that as strong earnings reports continue to roll in, if forward guidance remains solid and the trade wars are resolved (especially with China), investor sentiment will fall in line and we will see a risk-on rotation back into cyclicals as the market once again rewards stronger GARP qualities rather than just the momentum or defensive names. In fact, if you look closely at the December Baker's Dozen performance chart above, the brief but significant performance upturn in mid-August – after the announcement that talks with China had resumed – may have provided a glimpse of that potential.

The economy, corporate earnings, and Fed policy:

Next, let’s explore the strength in the economy and corporate earnings, the direction of interest rates, and the likely outcome of trade wars.

Numerous market pundits have been lamenting “protectionist” tariffs, a slowdown in housing, a too-strong US dollar, a spiraling financial crisis in emerging markets (led by Turkey and Argentina, spreading to Brazil, South Africa, and Indonesia), growth deceleration in Europe and China, a hawkish Fed, the yield curve threatening to invert, and a toxic domestic political environment with mid-term elections on tap, et al. And yet the US economy just keeps expanding. The BEA’s second estimate of GDP came in at a 4.2% annual rate in the second quarter (after an advance reading of 4.1%), which is the fastest rate since late-2014. Looking ahead, the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow model as of September 5 forecasts 3Q18 GDP annualized growth of 4.4%, while the New York Fed’s Nowcast model as of September 7 forecasts 2.2%. Friday’s jobs data was stellar, with unemployment remaining at 3.9%, while year-over-year wage growth clocked in at 2.9%. Consumer and business confidence, household consumption, and industrial production are all strong. ISM Manufacturing report blew away estimates (61.3 vs. 57.7 consensus), with strong production, a surge in new orders, and rising backlogs. Q2 earnings reports showed that 83% of US firms beat earnings estimates, driven by broad-based revenue growth (not just tax cuts) and record levels of profitability (around 12%). In his speech at the Jackson Hole Economic Symposium, Fed chair Jerome Powell said:

“Over the course of a long recovery, the U.S. economy has strengthened substantially…With solid household and business confidence, healthy levels of job creation, rising incomes, and fiscal stimulus arriving, there is good reason to expect that this strong performance will continue.”

Mr. Powell defended the FOMC’s plan for a slow-but-steady rise in the fed funds rate, but he also noted that as long as the unemployment rate remains low and inflation stable near the 2% target, he doesn’t see a need to accelerate the current path of interest rate increases. And St. Louis Fed CEO James Bullard suggested, “The Phillips Curve has disappeared and neither low unemployment nor faster real GDP growth gives a reliable signal of inflationary pressure” such that the Fed should watch the yield curve in deciding monetary policy.

They seem to be leaving open the door to adjustments to the current plan, and I believe these are the initial signals of a potential slowing of Fed rate hikes. Indeed, in contrast to the stated plan for two more rate hikes this year followed by four next year, which would move the fed funds rate from the current 2.00% to 3.50% by the end of 2019, CME Group fed funds futures (which essentially reflect the real-money bets by knowledgeable traders on what the Fed will actually do) suggest that the highest percentage likelihood (62%) by next September is a fed funds rate of 2.75% or less. But in the near term, fed funds futures currently place the odds of a rate hike at the upcoming September meeting at 99.8%, and by the December meeting, there is an 80% probability of another quarter-point rate hike. But for next year, the story might be quite different.

So, why would Powell slow things down if he thinks our economy is so solid? Well, there are a number of reasons. First of all, we aren’t an island unto ourselves, and the divergent monetary policies of central banks mean that Fed tightening has strengthened the dollar to the detriment of emerging markets (who carry dollar-denominated debt but earn their money in weaker local currencies), and rising interest rates can further hurt their ability to repay. Weaker currencies in these markets have contributed to the decline in commodity prices. Moreover, President Trump has made it clear that he will not be a happy camper if Fed tightening messes up our strong economic growth – which Trump is using as “cover” to fight his trade wars. In addition, some strategists would say that we appear to be on the verge of a “Fed inversion” of the yield curve. The 10-year Treasury yield closed Friday at 2.94% while the 2-year T-note is at 2.68%, so the closely-watched 2-10 spread is only 24 bps (less than one Fed 25-bp rate hike). You see, the Fed controls the short-end of the curve, and the 2-year note is heavily influenced by it, but the 10-year is much more market-driven (with Fed QE/QT having lesser impact), and you can bet the Fed doesn’t want to be responsible for inverting the curve.

What are these market dynamics pushing capital into US Treasuries and keeping the 10-year yield under 3.0%? Regular readers of mine know that I have been in the “lower for longer” camp regarding the 10-year Treasury yields for a long time (and lower long-term yields support equity valuations). These dynamics include geopolitical turmoil and aging demographics seeking safe yield, divergent central bank monetary policies and the much higher rates offered in the US (and the resulting “carry trade” from other countries), plus the structure of cap-weighted fixed income indexes whereby the large mutual funds and ETFs whose mandate is to track them must buy these Treasuries, even as new issuance floods the market.

But with the 10-year struggling to rise while the fed continues to raise on the short end, the flattening of the yield curve – according to the Fed chair himself – is essentially the marketplace telling the FOMC that it is already close to the “neutral rate” and may not need to raise much further. (The neutral rate is the level at which the Fed's target fed funds rate neither stimulates nor slows the economy, and Fed officials see it as being close to 3%.) Powell has previously stated that there is a lot of uncertainty surrounding estimates of the neutral interest rate, and that the FOMC therefore “will refer to many indicators when judging the degree of slack in the economy or the degree of accommodation in the current policy stance.”

The trade war with China:

As for the ongoing trade tensions. In my August article, I said that I would talk a lot more this month about China, so let’s have a go at it.

As you know, our President has been using various unconventional tactics to bring our various trading partners to the negotiating table to rework longstanding trade deals he believes have essentially subsidized the growth of other countries at our own expense. In other words, the temporary “hand up” long ago became a permanent “hand out” (aka entitlement) that they no longer need and we can no longer afford. Of course, the biggest offender is China, which has long used state ownership, subsidy, overcapacity, tariffs, forced technology transfer, patent violations, and outright theft of intellectual property (IP) to give their businesses an advantage in the global marketplace, while US businesses have looked the other way so as not to jeopardize their entry into the Chinese market. From China’s standpoint, it is much more expedient to appropriate the technology needed to drive growth than to go through the arduous and expensive process of R&D.

In a search for ways to continue its rapid growth in the face of the “law of large numbers” as an obstacle, the country has embarked upon its Belt & Road Initiative (aka BRI) and created a “Made in China 2025” strategic roadmap. BRI is an ambitious state-backed stimulus package for a slowing economy (and a path to global dominance) made up of a “belt” of overland corridors and a maritime “road” of shipping lanes that connect Asia, Africa, and Europe, encompassing 71 countries comprising over half the world’s population and roughly a quarter of global GDP. China continues to aggressively build infrastructure – like airports, subways, bullet trains, and renewable-energy facilities (including nuclear power plants with stolen technology). It also will allow China to employ its excess capacity while luring many poor countries into a “debt trap” in which China can, for example, acquire land in exchange for writing off their debts. As for the Made in China 2025 initiative, it has the goal of capturing 70% of global production in the emerging industries of the future. This includes seeking to become the global leader in artificial intelligence (AI) by 2030, supplanting the US. To accomplish all of this, I’m sure China’s leaders feel the need to continue appropriating the IP of others rather than to create and pay for it themselves.

But a trade war couldn’t come at a worse time for China, in my view. The country is burdened with a highly-levered and fragile financial system, with some estimates that total debt-to-GDP has risen over the past 10 years from roughly 140% to about 300% – and much of that debt went to build massive domestic infrastructure projects with little to no ROI. And given that it produces nearly 19% of global GDP, the ripple effects are also impacting commodity prices and emerging markets. Now it finds itself with slowing GDP growth as domestic demand and credit expansion has slowed, while new manufacturing data show slowing export orders. But China is better prepared today to deal with this, as it has implemented rigid capital controls, tighter regulation, and improved coordination between policymakers than in 2015 when it was still early in its deleveraging efforts. Thus, the government actually has had some success in navigating its way through the deleveraging process without upsetting aggressive growth targets.

For example, it has restricted the practice of large domestic companies issuing local debt to buy US dollar-denominated assets, which weakened its currency and its consumer purchasing power at a time when it needed to transition to more of a consumer-driven economy (rather than simply dump cheap goods on the world as a disinflationary manufacturing-driven economy, as it had done for so many years). Such capital controls have helped to greatly slow capital flight to other countries, and restrictions on rampant “shadow banking” and “wealth management products” (risky uninsured loans disguised as investments, generally offering high yields and sometimes guaranteed returns) have improved domestic and foreign confidence in the renminbi, thus allowing the currency to gradually depreciate (rather than rapidly plummet), and the People’s Bank of China (PBC) is better able to balance structural financial reform and deleveraging with monetary easing and fiscal stimulus as needed.

Nevertheless, the trade war has renewed pressure on the renminbi, which endured its biggest monthly fall against the U.S. dollar on record in June, when the trade war rhetoric became reality. This led the Chinese government to temporarily reverse its quantitative tightening policies, injecting liquidity back into the system by renewing QE, cutting taxes, and redoubling infrastructure investment. Although this is counter to its goal of loosening up its capital markets and currency exchanges in order to take its “rightful place” among the world’s major financial powers, it had to be done – especially if you look back to the crisis it faced with capital flight in 2015 when it burned through $1 trillion in foreign currency reserves to support the renminbi before finally succumbing to a devaluation. But this time around, capital flight was more contained, and China has not had to resort to a currency devaluation like it did back in 2015. Many experts think that another currency devaluation would likely undermine deleveraging effort, drive unlawful capital flight, ignite inflation, and stanch the growing interest of foreign investors in China’s capital markets. So, I would think another devaluation is a monetary “last resort,” and a strategic “last resort” retaliatory tactic might be the withholding from the marketplace of rare earth metals (which are critical ingredients in high-tech consumer and military electronics, and China is the world’s primary producer).

All in all, with its economy weakening and its stock market mired in a bear market, it seems to me that China can ill-afford any escalation in the trade war with the US. But by the same token, giving up the advantages it enjoys in our existing trade deals would also hurt it. So, it’s a bit of a Catch-22. But on balance, it seems to me that it would be better to appease Trump than let this drag out.