The central bank of the United States may hike its overnight lending rate in December. Committee members are also discussing plans to phase out the reinvestment of principal on balance-sheet securities. Translation? Borrowing costs are set to move higher.

The Fed is tightening for the first time in nearly a decade. In so doing, it is implicitly signaling faith in the U.S. economy’s ability to accelerate. The question investors might want to ask is whether or not that conviction is misplaced.

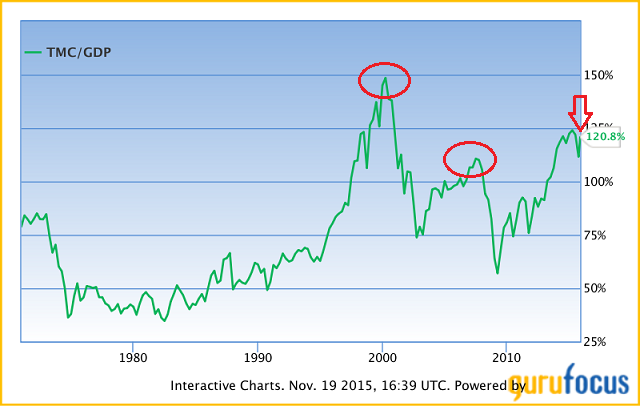

For one thing, if the U.S. economy continues to expand at the same sub-par recovery rate of 2.2% per year, stock valuations will move from overvalued to insanely valued. Consider the ratio of total U.S. stock market capitalization to the broadest quantitative measure of U.S. economic activity, gross domestic product (GDP). With total market cap at nearly $21.6 trillion and GDP at at roughly $17.9 trillion, the ratio sits at 120.8%. The historical average since 1970? About 72.5%.

Investors should recollect that Warren Buffett described Market-Cap-To-GDP as the “best single measure of where valuations stand at any given moment.” It follows that stocks are more expensive than they were before the financial collapse in 2008, though they are less expensive than they were prior to the tech wreck in 2000. If the ratio reverts to the historical mean of 72.5%? Then hold-n-hope advocates should prepare themselves for stock prices lose HALF of their current value.

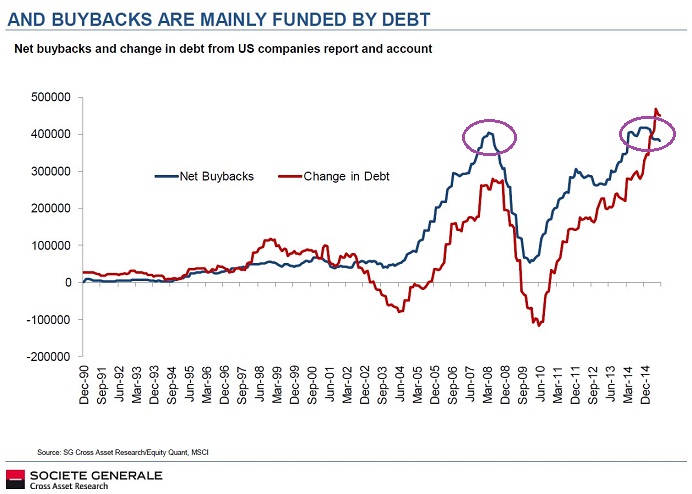

There are other concerns for investors should the economy prove less resilient than the Federal Reserve would like us to believe. Higher borrowing costs could force American companies to curtail the debt that they’ve raised to buy back shares of their own stock. Why is this so problematic? Not only would stock prices struggle to move higher if corporations are not buyers of as many shares as they have been in the past, but a lessening in stock buybacks would reduce the perception of corporate profitability.

Remember, when a public corporation earning $0.70 per share (EPS) has one million shares outstanding, lowering the share count by 10% to 900,000 artificially pushes profitability per share up to $0.778. Were any additional products or services sold? Nope. The accounting wizardly plays itself out in more “reasonable” price-to-earnings (P/E) ratios that investors often use to determine valuation levels.

Keep in mind, the buyback game has been happening for more than six-and-a-half years. Since 2009, debt-fueled share buybacks pushed earnings per share up 190%. Revenue from sales of products and services? Sales have increased an exceptionally modest 23%.

With buybacks primarily funded by debt, higher borrowing costs sank the debt-funded buyback connection that was part and parcel of the previous market collapse (10/2007-3/2009). Is it unreasonable to suspect that this connection will follow a similar pattern?

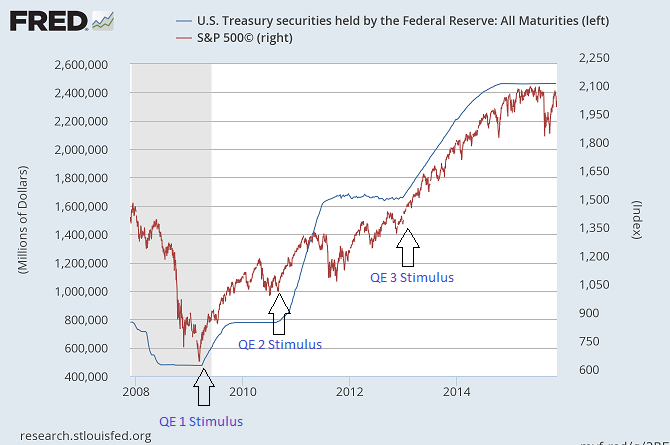

So if the Fed is wrong about the growth of GDP, and if it is wrong about the effect that higher borrowing costs will have on corporate credit expansion, stock valuations will surge. That’s true for Market-Cap-To-GDP. And that’s true for price-to-earnings (P/E). Yet there may also be an issue with the perception of a directional shift from a stimulative environment to a less stimulative one.

Take a look at the relationship between the S&P 500 and the Fed’s balance sheet throughout the current bull market run. Each time that the Fed created electronic dollar credits to buy assets, expanded its balance sheet, and subsequently lowered borrowing costs, stocks rallied dramatically. In each of the three instances since the 2009 stock lows where the balance sheet remained the same? Stocks struggled to make meaningful strides.

The possibility of the Fed reducing its balancing sheet. The danger of share buybacks rolling over. The unlikelihood of the U.S. economy breaking out in dramatic fashion. These headwinds to stock valuations as well as future returns – near-term and longer-term – are not easily dismissed. And that’s not even addressing the possibility that the domestic economy and/or the global economy weaken further.

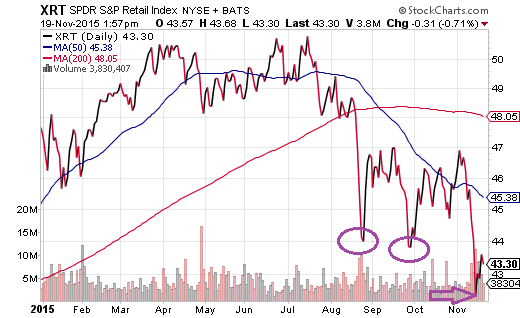

Is the consumer truly in great shape? Retail stocks in the S&P SPDR Retail Index (N:XRT) suggest otherwise. The exchange-traded fund hit new 52-week lows below the levels that we witnessed in the August-September sell-off.

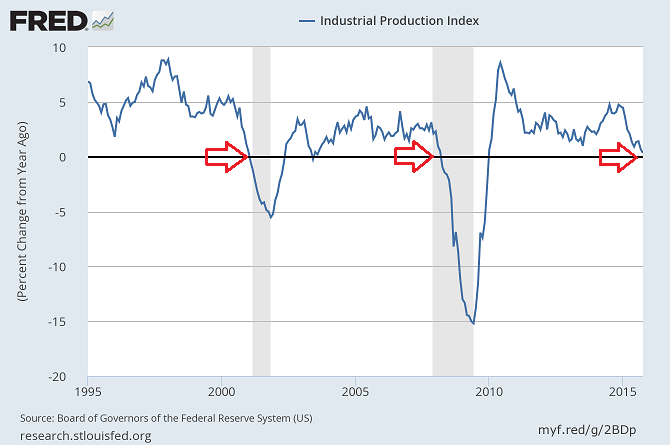

What’s more, we already know the recessionary struggles associated with manufacturers. Industrial production, which measures the amount of output from the manufacturing, mining, electric and gas industries, has fallen in nine of of the previous 10 months. There are few, if any, ways to put a positive spin on the declines in industrial production.

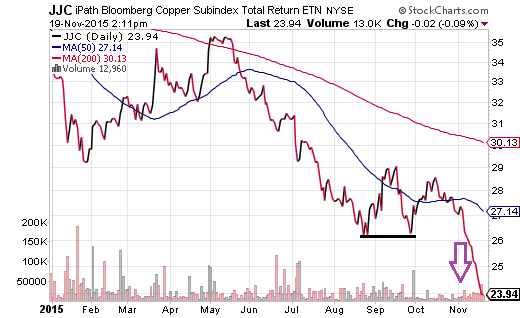

And then we have the Fed telling us that “global market risks have diminished.” Really? How much further does copper – the metal with a Ph.D. in economics – need to fall before global market risks reignite? The iPath Bloomberg Copper ETN (N:JJC) has not only broken below August and September lows, it might as well have fallen off a cliff.

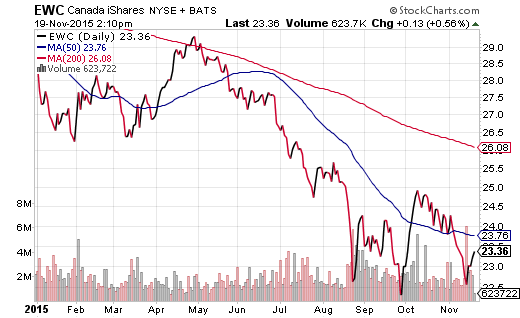

Similarly, how much further does oil need to drop before oil producing exporters begin falling apart. The iShares Canada ETF (N:EWC) is still toiling near its 52-week depths.

No Virginia, global market risks have not diminished. For that matter, global economic deceleration is still the prevailing prognostication by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). China’s economic output is decelerating. Japan is already in recession. And European quantitative easing is not stimulating borrowing activity the way that it did in the U.S.

In the end, all we have is the collective hope of voting members in the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). Hope that economic improvement will overcome lofty valuations and a pullback in corporate borrowing.

Don’t get me wrong. Based on everything from “tax-loss harvesting” to “window dressing” to momentum investing, the S&P 500 SPDR Trust (N:SPY) may still represent the best diversified stock holding around. How long one should stick with those brass tacks, however, is another matter entirely.