For the better part of 15 months, I have pounded the table for longer-term U.S. treasuries. Most financial pundits thought that I was nuts in December of 2013; they debated my scarcity premise throughout 2014 and they dismiss my relative-value argument here in 2015. About the only concession? The talking heads have often acknowledged that if the “poop” hits the propeller, the proverbial flight to quality would involve super-sized demand for the perceived safety of U.S. sovereign debt.

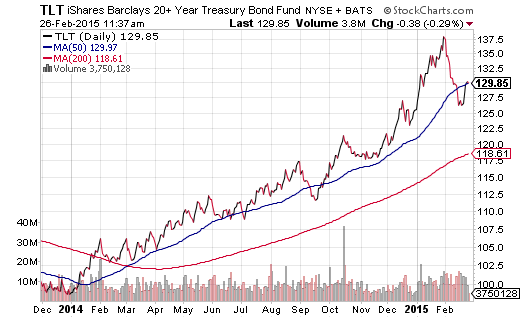

Nevertheless, there has been more conversation about people missing out on the opportunity to short oil or buy a 2% stock dip than investors neglecting opportunities in federal government IOUs. From my vantage point, however, the prospects for increasing long-bond exposure have not been quite as appealing since the iShares 20+ U.S. Treasury ETF’s (ARCA:TLT) 50-day trendline crossed above its 200-day one year ago.

When professionals erroneously slam the possibility of adding treasuries to a mix, they typically focus on ultra-low yields alone. Yes, the yields are deplorable. Heck the 10-Year barely competes with the dividend of the (ARCA:SPY). And yes, bonds are extremely overvalued from a simplistic perspective of the payment of interest.

Foreign Ownership

What they fail to recognize, of course, is that roughly half of our nation’s public debt is owned by foreign central banks and foreigners; 20% is owned by our very own Federal Reserve. Pensions, mutual funds, banks and insurance companies own most of the remaining securities. Now, think about it. Foreign central banks earn more on dollar-denominated AA/AAA treasuries than they earn on lower yielding, lower-rated assets in depreciating currencies; the relative value means there is little reason to sell. The Fed has no intention of dumping treasuries on the market for fear of killing favorable borrowing costs. In the same vein, pensions as well as bond mutual funds have rules about their allocation, while banks would rather earn 3% from a risk-free 30-year treasury than 3.5% from Joe and Josephine Shmo’s mortgage.

It follows that the demand for U.S. treasuries across the globe is extraordinary, yet the supply is undeniably limited. This is scarcity. What’s more, when you add in other factors – relative value against scarce developed world bonds, need for perceived safety, economic deceleration – the “Fed is raising overnight lending rates” counter is entirely myopic.

Perhaps ironically, some stock advocates are using scarcity to explain why stocks are poised to continue their remarkable run without a hitch. In brief, believers posit the following: Retiring/semi-retiring baby boomers are set to live well into their eighties and nineties, meaning that the demand for stocks held over 30 years will be higher than anyone could have imagined. On the other hand, the percentage of available shares in the S&P 500 has dwindled considerably due to remarkable share buyback activity by component corporations. In fact, they argue, the laws of supply and demand pretty much trump traditional measures of valuation and, for that matter, human psychology in panics.

One such stock advocate is an “almost-famous” commentator who I respect (even when I do not agree with him). Joshua Brown of the Reformed Broker wrote about scarcity of stocks on 2/25:

They’re living way longer than their parents did and way longer than they’d originally expected to. 25 percent of them will make it into their nineties. What do they need more than anything? It sounds crazy, but they need stocks. Bonds aren’t going to cut it for a thirty year retirement…

And stocks are scarce… Buybacks have shrunk the quantity of S&P 500 company shares…

There are quite of few problems with the scarcity argument as a sole driver for market-based securities. Remember, scarcity in treasuries trumps the severely overvalued mantra because there’s more to the story, including relative value with comparable treasuries clear across the developed world, safe harboring for those who need some assurance of capital preservation and a well-delineated slowdown in global economic activity. However, scarcity in stocks is unlikely to trump ridiculous overvaluation in equities ad infinitum. I suppose one can also explain that European and Asian injections of liquidity will also find their way into scarce stocks, though I suspect the high probability of recessionary pressures weighing on the U.S. in the near-to-intermediate term will make participants rush for the exits.

Josh Brown may well remember the 2000-2002 dot-com disaster as a fresh-faced University of Maryland graduate circa 1999. He may even recall how the “New Economy” had been expected to change the rules of investing altogether; that is, traditional measures of valuation no longer applied. Not only was Dow 40,000 and Dow 100,000 right around the corner, but trailing P/Es of 30, 45 or 60 simply reflected the realities of a new economic ideal. (Or so people erroneously thought.)

Here in 2015, Josh waxes philosophic about a scarcity paradigm:

“There aren’t ten Disneys, there’s just one. There aren’t two Apples, there’s one.”

Of course, there was only one Eastman Kodak founded by George Eastman in 1888. My first camera as a nine-year old in 1976 was a Kodak, when the company owned 85% of camera sales in the U.S. as well as 90% of film sales. As late as 2001, Kodak held the No. 2 spot in U.S. digital camera sales. Unfortunately, digital pictures moved to the world of smartphones and tablets. (Thank you Apple!) How did it play out for Kodak buy-n-hold-n-hopers? Existing stockholders were wiped out by Kodak’s bankruptcy.

Great Companies CAN Go Down

I suppose I could talk about General Motors (NYSE:GM), Lehman Brothers, K Mart or Pacific Gas & Electric (NYSE:PCG), but the reader should get the point. The stock of great companies can go down… quite a bit. Even Walt Disney Company (NYSE:DIS) is quite capable of falling 57%. (See chart below.) The math of loss does not make a recovery from 57% losses quite so easy, nor does human psychology favor anyone’s willingness to watch their dollars disappear. That’s why investors need to insure against monstrous losses, particularly in an absence of tailwinds from six years of quantitative easing and six-plus years of zero-percent interest rates.

Yes, my clients still own overvalued stocks; we still own core holdings like Vanguard Dividend Appreciation (NYSE:VIG), iShares S&P 100 (OEF) as well as Vanguard Mega Cap Growth (NYSE:MGK). That said, if one of these assets falls below and stays below a 200-day moving average, I am likely to reduce exposure. I may employ stop-limit loss orders to sell some or all of satellite ETF assets like Pure Funds Cyber Security ETF (HACK) and SPDR Select Health Care (ARCA:XLV). Finally, when a preponderance of volatility measures and contrarian indicators give me reason to anticipate benefit from multi-asset stock hedging, I invest in the FTSE Custom Mutli-Asset Stock Hedge Index. Multi-asset stock hedging gives investors a diversified means for pursuing profits above T-bills.