The previous decade’s financial crisis did not begin in earnest until 2008. Bear Stearns. Lehman Brothers. AIG. And yet, the warning signs had appeared long beforehand.

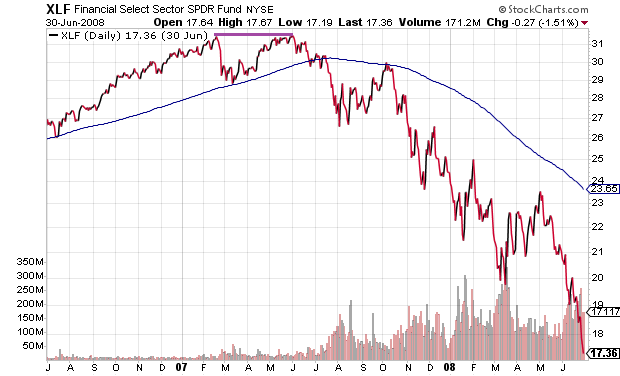

Real estate sales had turned negative on a year-over-year basis in 2006, even as prices kept climbing. Meanwhile, SPDR Select Sector Financials (NYSE:XLF) logged -21% in 2007, even as the broader S&P 500 had notched a record high as late as October.

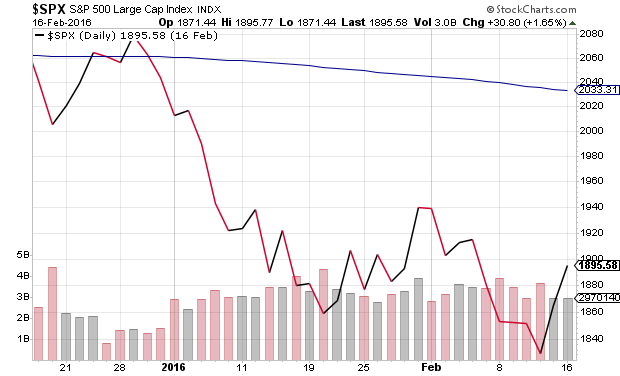

In mid-2015, European financial stocks peaked. And in much the same way that bearishness in U.S. financials preceded a collapse of market-based securities across the globe by as much as 9 months, iShares European Financials (NASDAQ:EUFN) have served up similar warnings.

Clearly, few believe that European banks can make money in a negative interest-rate environment. Moreover, European stocks have suffered more than other equity markets since last summer.

Yet the notion that systemic risks will remain geographically contained is remarkably optimistic. Can contagion be avoided by bailing out the “too-big-too-fails?” And if so, which European governing body would be capable of orchestrating a bail-in or bail-out as quickly as the Federal Reserve has done in the past? The idea that a governing body will be able to provide banks with needed capital to save the system may be fanciful.

Heavily indebted nations across the developed world (U.S. included), have fewer and fewer ways to increase spending for the benefit of economic growth. The only trick left is to force rates lower for the purpose of debt-fueled consumption and to nurture the wealth effect.

Unfortunately, 25% of the world’s sovereign debt is already negative. And the Global Developed Sovereign Bond Index? Its yield of 0.49% is not adequately compensating bondholders for the risk they are taking.

The bigger problem? Governments must keep pushing rates lower in order to service existing debts. Any trend toward normalizing would result in economic hardship, defaults and large losses for government-sponsored pensions.

Perhaps the biggest irony is that the Federal Reserve’s decision to suppress interest rates for far too long in the 2000s is the primary reason for the insanely speculative real estate bubble and subsequent economic collapse that has been dubbed, “The Great Recession.” Not that Greenspan, Bernanke or Yellen would admit it. After all, the Fed later decided to “double down” by suppressing overnight lending rates near the zero-bound for seven-and-a-half years already.

What happened to stocks when the Fed attempted to nudge its overnight lending rate a piddling quarter point back in mid-December? A violent 12%-plus correction for the S&P 500. Note: The recent stock euphoria did not kick in until the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of Japan (BOJ) promised additional increases in electronic money printing via quantitative easing (QE), with the Fed itself downgrading its four rate-hike plan to “one” or “two.”

Is the developed world trapped? I would say so. Economic weakness encourages monetary policy leaders to cut overnight lending rates or create electronic currency for the purpose of acquiring more market-based assets. Stock and bond prices rise alongside additional QE around the globe, irregardless of their underlying risks or fundamentals. In contrast, if economic activity genuinely improved, stimulus withdrawal would likely spark market-based shocks that are frighteningly similar to the one witnessed in January-February of this year.

I am hardly the only one that believes the Fed has “smacked the pooch.” Consider Kevin Warsh’s comments on CNBC last week. The former Fed governor laughed off the idea that his former financial institution makes decisions based on incoming economic data. Warsh said:

In the darkest days of the 2008 crisis, when markets were falling, I have to admit getting asset prices up, trying to get markets up… nothing wrong with that. We’re supposed to respond to financial crises. But that was seven and eight years ago. This preoccupation with your show, and with the Bloomberg screen, and with stock prices…that is not the right worldview for central bankers. The Fed had a long window to tighten policy, to raise rates – 2013, 2014, 2015 — and it strikes me they missed that wide-open window.

Indeed!

So now the investment community rallies around U.S. corporate profits and corporate sales that have descended for five consecutive quarters. It rallies around a domestic economy that expanded a timid 1% over the previous three quarters. And it ignores stock valuations that have rarely been as lofty as they are.

A number of folks regularly opine that they have to put their money somewhere, and that 0%-1% yielding cash is not a solution. I disagree. Cash is a terrific asset when the pursuit of reward in stocks and bonds comes with the risk of substantial loss. (If only for a brief period of time.)

Am I talking about selling everything and running for the hills? No, I am not. I am talking about a 25%-30% buffer against volatility; I am talking about waiting for better value.