Some New Yorkers may hate me for saying so, but I did not care for Joe Namath. I never liked Mark Gastineau either. I am (and have always been) a devout fan of the New York Giants. And if you love “Big Blue” – if you revere the “New York Football Giants” – there’s a pretty good chance that you detest the New York Jets.

Why do I bring this up? Sometimes, things get out of control.

Thirty years ago in 1986, I went to the Meadowlands with a friend to see the Los Angeles Rams battle the New York Jets. I wore my Phil Simms jersey to show my allegiance to the Giants. Meanwhile, my friend waved a Rams banner enthusiastically. (We were nervy 19-year olds… what did we know?)

What we should have known is that football fanatics on the East Coast rarely appreciate ne’er-do-wells cheering for the opposition. What’s more, stadium attendees tend to drink large amounts of alcohol. Mix in the fact that the Rams had been beating the living daylights out of the Jets, and the stage had been set for disorder.

People started in with “colorful” insults. Then a few miscreants began throwing cans, pretzels and programs. I remember thinking that someone might actually take a swing at me.

At one point, I said to Anthony, “This is getting way out of hand.” That was right before a heavy object smacked him on the bridge of his nose. His blood dribbled down his chin and onto his banner. Within seconds, security guards appeared on the scene, and they quickly provided us with an escort out of the facility so that we would be safe.

What I recall most about the incident is just how rapidly the environment deteriorated. At the start of the event, the jousting between Giant-loving New Yorkers and Jet-loving New Yorkers had been innocuous. On the surface, the environment may even have appeared friendly. By the 4th quarter, however, circumstances had spiraled out of control.

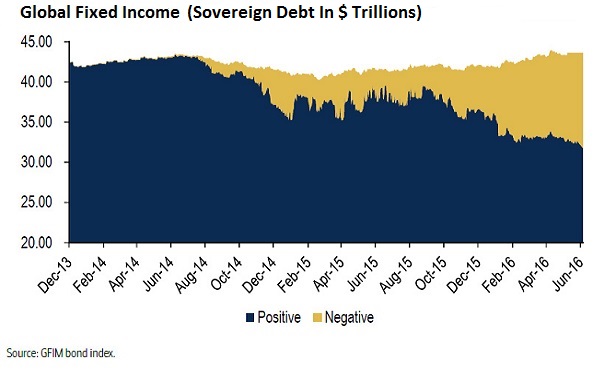

How does my anecdote relate to the world of market-based securities? Compare the percentage of negative-yielding government bonds in June of 2014 against the percentage of negative-yielding government bonds in June of 2016. Two years ago, few experts could even conceive of the concept of a negative bond yield. Today, however, central banks around the globe have printed so much in the way of electronic money – they have acquired such a large quantity of the supply of government obligations – we now see 25% of the world’s sovereign debt with negative interest rates. From 0% to 25% in just two years.

I do not think that many investors recognize the extent of the insanity taking place. I genuinely believe that many market participants are foolishly dismissing a market-based environment that has gone haywire.

For one thing, lower and lower yields do not perpetually propel equity prices forward. For that matter, lower interest rates do not terminate the high probability of bear market wealth destruction. One can look at the four bear markets that occurred during the ultra-low interest rate period between 1936-1955 to increase his/her understanding of stocks and Treasury bond yields.

More recently, government bonds on the Swiss yield curve began turning negative two years ago. Yields all along the Swiss yield curve have been trending lower ever since. Today, virtually all government bonds on the Swiss yield curve have gone “sub-zero.” It follows that if lower yields for longer are all the rage, wouldn’t the exceptionally low Swiss bond yields be a boon to Swiss stocks? The iShares Switzerland Capped ETF (NYSE:EWL) has produced a return of approximately -10% over the last two years.

The third largest economy in the world, Japan, may be the poster child for incredibly low (below zero) interest rates. The Bank of Japan is so “off the rails” that it owns nearly all of the country’s government obligations. (Who else besides central banks would continue buying sub-zero promises from Japan? Who else would pay the Japanese government money to receive less money back at maturity?)

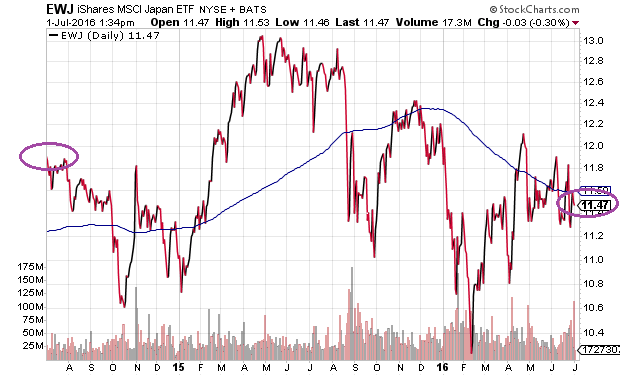

Silliness notwithstanding, if the cost to borrow is so incredibly beneficial for Japanese consumers and businesses, why aren’t we seeing it translate to a booming Japanese stock market? The iShares MSCI Japan ETF (NYSE:EWJ) logged roughly -3% over the last two years.

Okay, then. Over the last two years, lower and lower interest rates have not been able to send European or Japanese stocks skyrocketing. On the flip side, one might argue that lower and lower interest rates HAVE supported stock wealth; that is, in the absence of central bank actions across the globe, perhaps equities would be free-falling right now. Nobody knows for sure, but it remains a possibility.

Another possibility is a bit more nuanced. Specifically, there are those that believe negative interest rate policy (NIRP) might be counter-productive for the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan. Perhaps a world where 25% of the sovereign debt in existence with a yield below 0% – a world where lenders compensate borrowers for the privilege of lending – is detrimental. So these stock markets are suffering the depreciation in price. In contrast, lower and lower yields in the U.S. are still wonderful because U.S. corporations can keep borrowing dollars on the ultra-cheap and plow the proceeds back into shares of their respective company stock.

Sorry, folks. I am not buying it. U.S. corporate profits peaked in September of 2014. U.S. Total Business Sales crested in August of 2014. And Vanguard Total U.S. Stock Market (NYSE:VTI) is only up about 5% over the last two years (most of which came in the last 5 days) versus a 25% surge for the much-maligned iShares 20+ Year Treasury Bond Fund (NYSE:TLT).

Can we really evaluate the trend over the last two years – deteriorating sales, disintegrating profits, plummeting global bond yields – and say that the central banks around the world are strengthening economies? Perhaps record low yields on 10-year and 30-year Treasury bonds prevent a bearish bloodbath for stocks; perchance the Federal Reserve has succeeded at keeping the wealth effect from falling apart. Yet many are taking extraordinary risks for paltry rewards.

It gets worse. In the absence of a renaissance for global economic output, faith in central-bank decision making may erode. And that it includes faith in the U.S. Fed. Let’s hope that it does not happen so rapidly that it catches unprepared market participants fighting to get out a very narrow exit door.