Rember Abeconomics and the BOE buying lots of stocks and other assets? One analyst has states that it’s an official monetary policy failure

During September last year, the decision by the Bank of Japan to overhaul its monetary policy lead analysts at Citigroup to declare an end to the era of quantitative easing. Citi analyst Willem Buiter wrote in a research note at the time:

“The BoJ’s September 21 decision to move to a framework of 10-year yield targeting marks the beginning of the end of QE (the focus on asset purchase size and balance sheet size as primary instruments of monetary policy), with notable read-through to other central banks.”

However, by the first quarter of 2017, analysts had changed their view and, after a bout of poor inflation figures, proclaimed that the BoJ “shouldn’t be in a hurry to exit QE”:

“The lingering of deflation risks, together with the exports-dependent economic recovery, should prompt the BOJ to adopt a cautious attitude on monetary policy. While the BOJ will conduct monthly bond purchases in a flexible manner in response to the development in market conditions, it shouldn’t be in a hurry to exit QE or to raise the yield target. No policy change is anticipated at April’s BOJ meeting.”

Japan: Monetary Policy Failure says CLSa – what is next

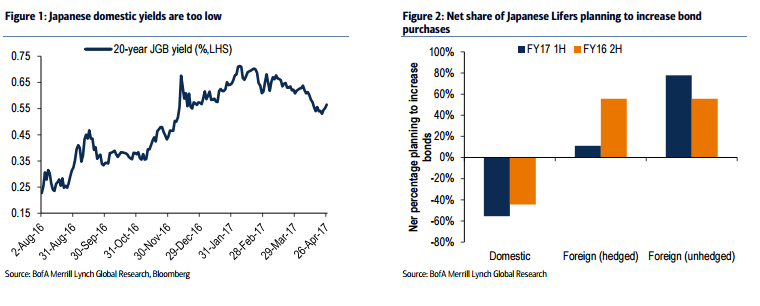

According to CLSA Benthos, the problem Japan’s policymakers now face is that rather than stimulating demand, all QE has done is to depress bank earnings and increase savings rates.

According to the report, when central bank governor Kuroda arrived, interest rates on new loans were just 96 basis points, and have since declined to 18 basis points and to a certain extent, this has increased the demand for borrowing. When Kuroda arrived, only 70.9% of banks’ deposits were being lent out, and since then loans have risen by 9.4%. At the same time, deposits have risen 16.6% meaning that the loan/deposit ratio has declined by 4.4 points to 66.5.

At the city banks, the loan/deposits ratio has fallen as much as 10.5 points, to 53.8% meaning that around half of the banks’ deposits are not being lent – these figures are despite the fact that Japanese lending standards are some of the easiest on record.

And it’s not just banks that are struggling with too much cash. According to the CLSA report, 56% of TOPIX non-financials are net cash and households have 52% of their assets in cash. Money is just not making its way into the economy. M3 is at 3.4%, zig-zagging between 2.4% and 3.4% since April 2013, only Switzerland is slower.

Rather than continuing to depress rates, it seems policymakers need to cook up new ways to get consumers and firms spending again. Efforts to convince businesses to pay more to staff have, so far, fallen flat. Although there could be green shoots on the horizon, according to the Nikkei Asian review, Japan’s government is seeing signs of a consumer uptick, “a sign that a virtuous cycle starting with an improved employment environment is taking hold.”

An increase in domestic demand is also noted with recent statistics showing “sales turning around to growth for retailers including department stores and supermarkets, and automobile sales are rising on the year.” Domestic demand has outstripped supply for two straight quarters, starting with October to December. So maybe things are looking up for Japan but it’s clear that QE has not achieved the desired impact policymakers believed it would do.