Next Tuesday will mark four weeks since Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi made his surprise demonetization announcement that has sent shockwaves throughout the South Asian country’s economy. In an effort to combat corruption, tax evasion and counterfeiting, all 500 and 1,000 rupee banknotes are no longer recognized as legal tender.

I've previously written about the possible ramifications of the “war on cash,” which is strengthening all over the globe, even here in the U.S. Many policymakers, including former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers, are in favor of axing the $100 bill. In May, the European Central Bank (ECB) said it would stop printing the 500 euro note, though it will still be recognized as legal currency. The decision to scrap the “Bin Laden” banknote, as it’s sometimes called, hinged on its association with money laundering and terror financing.

Electronic payment systems are convenient, fast and easy, but when a government imposes this decision on you, your economic liberty is debased. In a purely electronic system, every financial transaction is not only charged a fee but can also be tracked and monitored. Taxes can’t be levied on emergency cash that’s buried in the backyard. Central banks could drop rates below zero, essentially forcing you to spend your money or else watch it rapidly lose value.

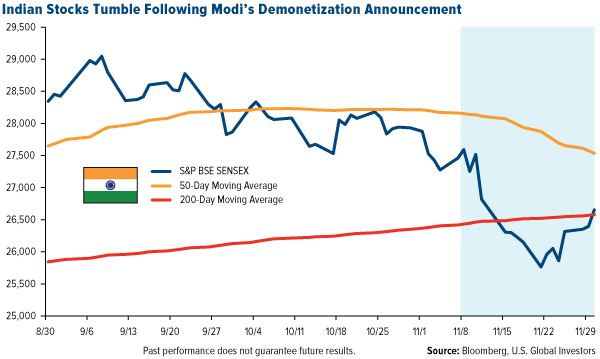

Inevitably, low-income and rural households have been hardest hit by Modi’s currency reform. Barter economies have reportedly sprung up in many towns and villages. Banks have limited the amount that can be withdrawn. Scores of weddings have been called off. Indian stocks plunged below their 200-day moving average.

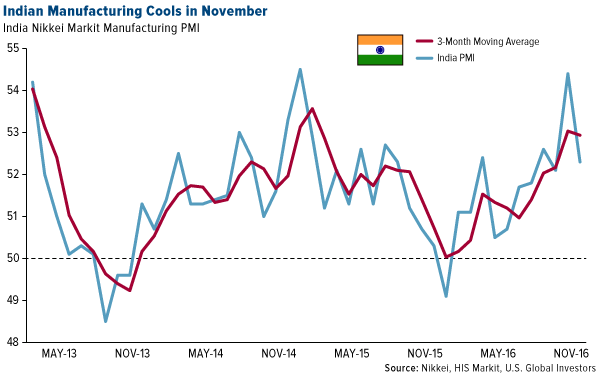

Demonetization has also weighed heavily on the country’s manufacturing sector. The Nikkei India Manufacturing PMI fell to 52.3 in November from October’s 54.4. Although still in expansion mode, manufacturing production growth slowed, possibly signaling further erosion in the coming months.

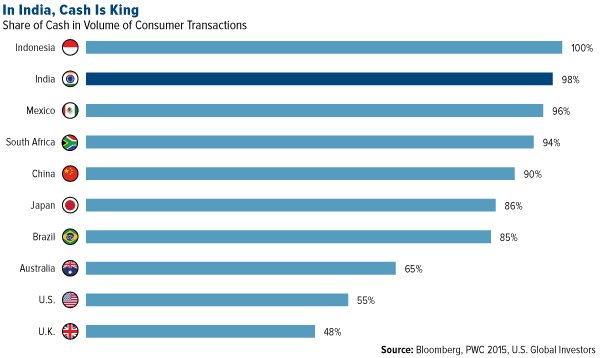

India Runs on Cash

The two Indian bills in question, worth $7.50 and $15, represented an estimated 86 percent of all cash in circulation by value. No two bills in the U.S. so dominate transactions quite like the Rs500 and Rs1,000 notes, but imagine if tomorrow the Treasury Department killed everything north of the $20 bill. Despite the widespread availability and acceptability of electronic payment systems, this would be devastating to many American consumers who prefer cash or who are underbanked.

Because India’s economy relies predominantly on cash, the effects will be far greater. ATMs are scarce, and few rural Indians have a credit or debit card. An estimated 600 million Indians—nearly half the country’s population—are without a bank account. Three hundred million have no government identification, necessary to open an account. By comparison, about 7 percent of Americans are unbanked, with an additional 20 percent underbanked, according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC).

This is one of the main reasons why Indians have traditionally held gold in such high demand. Many have little faith in banks and other financial institutions, preferring instead to store their wealth in something more reliable and tangible. So great is Indians’ appetite for the yellow metal that prices have historically surged in September, following the end of the monsoon season and ahead of Diwali and the wedding season, when gifts of gold jewelry are typically given.

Suresh Jain, owner of India’s B.J. Jain Jewellers, as quoted in the Financial Times, said,

Gold is a need of the [Indian] people...It is not a luxury item. It is essential.

Ironically, though, Modi’s demonetization scheme will likely hurt gold demand in the long run, “by dramatically reducing the stock of black money hitherto used in a large chunk of purchases,” according to the Financial Times.

In the three days following the announcement, Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL) iPhone sales surged, equaling three quarters of the sales that typically happen in a month, as people tried to move their black money. Shopkeepers obliged by backdating receipts. Demand for other luxury items, such as Rolex watches, also surged.

Last year, our office was visited by the founders of MoneyOnMobile, which provides full point-of-sale services to Indians who don’t have ready access to ATMs. Think of it as the Indian version of Square. It’s likely that with demonetization wiping out so much paper currency, demand for services such as MoneyOnMobile’s will skyrocket.

Good Intentions, Bad Execution

Admittedly, high cash usage often comes with a cost. In 2013, research firm McKinsey found a strong correlation between high cash usage and the size of a country’s shadow economy. The size of India’s own shadow economy—which includes black market transactions and undeclared work—is roughly a quarter the size of gross domestic product (GDP).

Indeed, India suffers from a serious rash of corruption, which hurts honest, hard-working families. According to Transparency International, the South Asian country ranks 76 out of 168 countries in its 2015 Corruption Perceptions Index. In May, Indian government data showed that a scant 1 percent of Indians pay income taxes.

So yes, corruption is a problem. But in the case of ditching paper money altogether, the cure is worse than the disease.

In a New York Times op-ed, Indian economist and World Bank Vice-President Kaushik Basu strongly criticized the policy, rightly pointing out that it’s,

mostly hurting people who aren’t its intended targets...The government’s wish to tackle these problems is laudable...but demonetization is a ham-fisted move that will put only a temporary dent in corruption, if even that, and is likely to rock the entire economy.

I agree. Demonetization will hurt low-income and rural families the most, while those who’ve benefited from the country’s deep shadow economy will likely find other avenues to traffic in corruption.

Disclaimer: All opinions expressed and data provided are subject to change without notice. Some of these opinions may not be appropriate to every investor. By clicking the link(s) above, you will be directed to a third-party website(s). U.S. Global Investors does not endorse all information supplied by this/these website(s) and is not responsible for its/their content.

The S&P BSE SENSEX (S&P Bombay Stock Exchange Sensitive Index), also-called the BSE 30 or simply the SENSEX, is a free-float market-weighted stock market index of 30 well-established and financially sound companies listed on Bombay Stock Exchange.

The Nikkei India Manufacturing PMI is based on data compiled from monthly replied to questionnaires sent to purchasing executives in over 400 industrial companies. The panel is stratified by GDP and company workforce size. The manufacturing sector is divided into the following eight broad categories: Basic Metals, Chemicals & Plastics, Electrical & Optical, Food & Drink, Mechanical Engineering, Textiles & Clothing, Timber & Paper and Transport.

The Corruption Perception Index, developed in 1995 by Transparency International, ranks almost 200 countries on a scale of zero to 10, with zero indicating high levels of corruption and 10 indicating low levels. Developed countries typically rank higher than developing nations due to stronger regulations.

Holdings may change daily. Holdings are reported as of the most recent quarter-end. None of the securities mentioned in the article were held by any accounts managed by U.S. Global Investors as of 9/30/2016.

U.S. Global Investors, Inc. is an investment adviser registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission ("SEC"). This does not mean that we are sponsored, recommended, or approved by the SEC, or that our abilities or qualifications in any respect have been passed upon by the SEC or any officer of the SEC.

This commentary should not be considered a solicitation or offering of any investment product.

Certain materials in this commentary may contain dated information. The information provided was current at the time of publication.