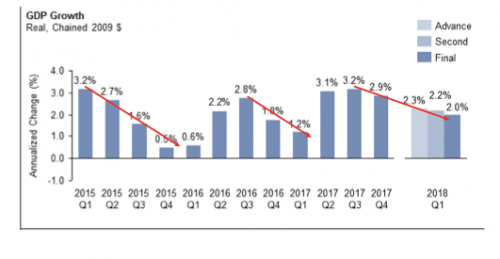

The economy, as measured by gross domestic product (GDP), grew at 4.2% in the second quarter. It slowed to 3.5% in the third quarter. Meanwhile, Q4 projections have been coming in closer to 2.9%.

An optimistic “take” would be to exclaim that the 2% pace that has been the hallmark of the current expansion is now in the rear-view mirror. For 2018 and beyond, we have kicked it into a higher gear (3%) due to tax cuts and regulation curtailment.

A less rosy perspective? Economic growth has peaked.

Keep in mind, the U.S. economy required $3.5 trillion in Federal Reserve bond-buying stimulus and $9.8 trillion in new government debt to maintain the “New Normal” (2%) from 2009-2017. Tax cuts financed by $1 trillion plus in new debt in 2018, coupled with a Fed that has yet to reduce its balance sheet meaningfully ($4.1 trillion), has taken us to a 3% annual average temporarily. Going forward? Federal Reserve balance sheet reduction combined with tighter rate policy will slow the economic growth train.

In the recent past, economic contraction around the globe (Q3 2015 – Q1 2016) nearly brought the U.S. to its knees. The Bank of Japan and the European Central Bank provided shock-n-awe levels of bond buying with electronic currency credits. The U.S. Fed slashed plans for four rate hikes down to a token hike slated for the end of 2016. And the U.S. economy averted recessionary pressure.

In a similar vein, the economy began slowing once again as the presidential election year wore on. Then, the game-changing promise of less regulation and lower taxes gave a jolt to business confidence. Asset prices that had been laboring for nearly 22 months also moved skyward.

More recently, financial markets have been signalling a slowdown — one that is largely associated with higher borrowing costs. Is it any wonder that two stock market corrections in 2018 came about when the 10-year yield catapulted 50 basis points in a span of 4-6 weeks?

There’s an ironic “stat” when it comes to experiencing two 10%-plus corrections in a single year. According to Gluskin Sheff’s David Rosenberg, when all three major stock averages averages (Dow, S&P 500, Nasdaq) dropped 10%-plus twice in a single year, bearish stock depreciation ambushed unwary participants.

The years? 1973, 1974, 1987, 2000, 2001, 2002 and 2008.

To be fair, the Nasdaq only goes back to 1971. The data are limited. Nevertheless, 50%-like maulings occurred in three instances — 1973-1974, 2000-2002 and 2008-09. The lone exception (1987) featured the single worst percentage drop in history. (Note: The Dow dropped 22.6% on 10/19/87.)

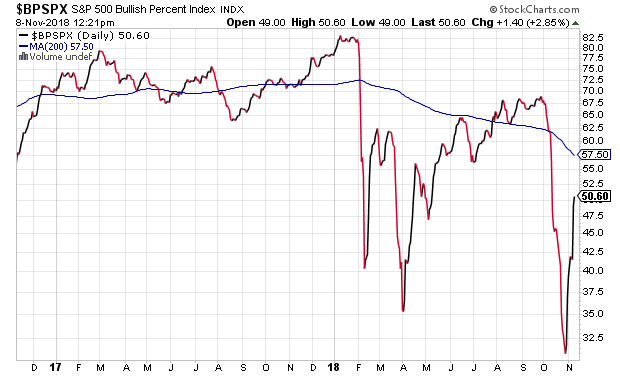

Setting aside previous bears, the current technical picture is uninspiring. The new September stock highs for the S&P 500 came on less than 70% participation. (The January peak occurred at 82%.) Half of S&P 500 stocks are struggling in a downtrend even after the post-election bounce. And the slope of the 200-day moving average for bullish percentage is accelerating to the downside.

Granted, stocks could easily stage a year-end rally. Active mutual fund managers often feel compelled to catch up with their passive indexing counterparts in November and December. The overwhelming number of corporations will have exited their blackout periods for buying back shares. And dip buyers may continue to do what has worked so well for so long.

Still, many may be overlooking the economic weakness in key areas. With rates at 10-year highs and home prices sitting at all-time records, U.S. consumers are barely applying for mortgages anymore. For all intents and purposes, mortgage applications are as anemic as they were in the year 2000.

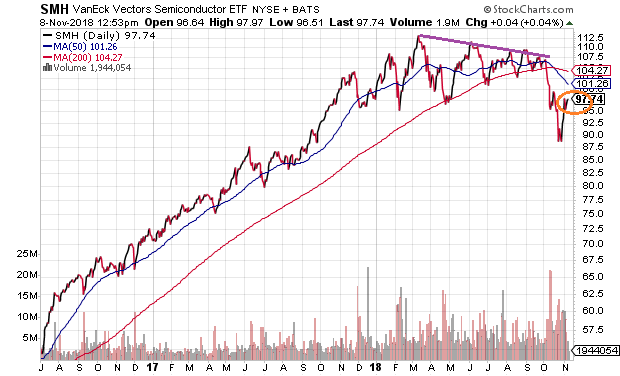

Perhaps more alarming? October was one of the worst months for semiconductors in the past decade. Having a longstanding reputation as a leading indicator for technology stocks, the sub-sector’s downtrend may be a cautionary sign.

Think of all the “chippies” that gave poor forward guidance on revenue and earnings. Micron (NASDAQ:MU), Advanced Micro Devices (NASDAQ:AMD), Cypress Semiconductor (NASDAQ:CY), Lattice Semiconductor (NASDAQ:LSCC) and Texas Instruments (NASDAQ:TXN) come to mind.

The evidence on semmiconductor stocks serving as a harbinger can be seen in the 2000-2002 tech wreck. Notice what transpired for semiconductor stocks after the 50-day moving average crossed below the 200-day moving average. In fact, the brutal bearish price decimation in “semis” eventually occurred across the entire technology landscape.

In spite of economic enthusiasm at present, there are significant challenges for real estate and tech in the near future. Toss in year-to-date losses for energy stocks and basic materials stocks and the notion that the U.S. economy will continue to fire on all cylinders becomes suspect.

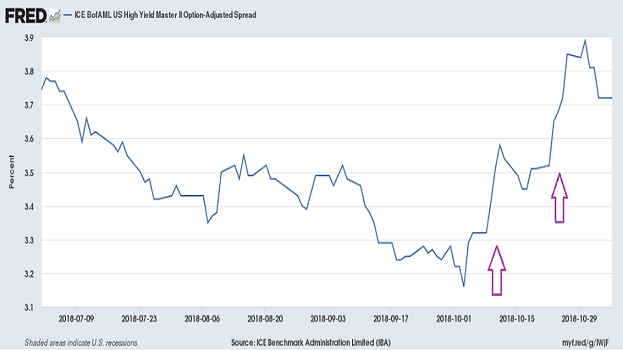

What am I watching closely? Corporate credit spreads. When the spread between junk bond borrowing and Treasury bond equivalents widens, a risk-off environment often materializes. Those concerns right now, however, appear contained.

On the flip side, the more expensive it becomes for low-rated companies to borrow money, the more likely they will lay off employees and/or end buyback programs. It would not take much for a few big-name defaulters to spark a wave of selling in junk bonds as well as equities.

Don’t think the scenario is in the cards? I think it depends entirely on the Fed.

The further the rate hikes go and the more the central bank lets bonds roll off its balance sheet, the greater the possibility over-leveraged corporate debtors will finally fail. Specifically, staying in business through the consistent refinancing of debt will cease to be an available option.