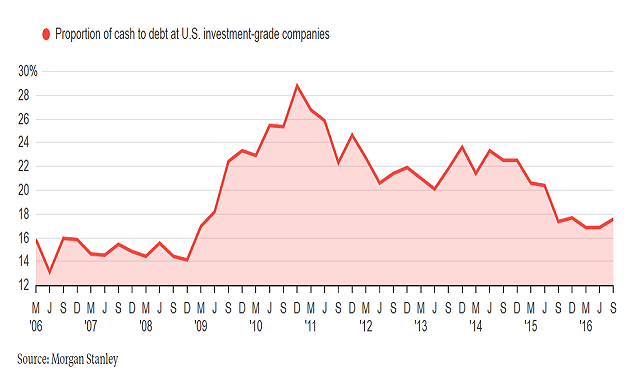

Corporations have more than doubled their debt levels since 2008’s financial crisis, from $3.5 trillion to $8.1 trillion. They are carrying more leverage (e.g., debt-to-revenue, debt-to-EBITDA, etc.) than at any point since the 2000-2002 tech wreck. And the cash relative to the debt on corporate books has been dropping precipitously.

Granted, one can choose to emphasize the inexpensive nature of the credit. Why shouldn’t companies borrow by the boatload as long as interest rates remain relatively contained?

For one thing, corporate borrowing costs may not always remain as friendly as they are today. At least $1 trillion of the debt will come due within the next five years and the debt will need to be refinanced (a.k.a. “rolled over”) in the future when the borrowing may be more expensive. It follows that a much larger percentage of corporate revenue may wind up going toward interest payments.

Equally troubling, the Federal Reserve demonstrated a determination to raise borrowing costs with a 0.25% hike at Wednesday's March 15 meeting. Fed Chair Janet Yellen explained that removing ultra-accommodating rate policy “reflects the economy’s continued progress.” However, over the last few years, job growth has slowed from 2.5% to 1.4%. Gross domestic product (GDP) has been decelerating, with the Atlanta Fed’s model predicting expansion of just 0.9% in Q1. And retail sales in February haven’t been this dismal since last August.

Indeed, stocks rallied on Yellen’s portrayal of economic acceleration. But the bond market? Instead of yields climbing as many would have anticipated in a tightening phase, yields declined across the curve. Both the 5-year Treasury yield and the 10-year Treasury yield dropped nearly 10 basis points from 2.1% to 2.0% and from 2.6% to 2.5% respectively. Perhaps the bond market is not “buying” the Fed’s economic cheerfulness.

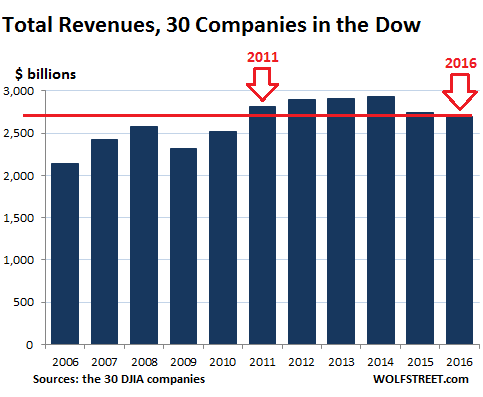

Third, if an economy is humming, shouldn’t corporate borrowers be increasing their income hand over fist? Instead, S&P 500 companies are growing debt at a double-digit clip (10%-plus), while struggling to produce significant revenue growth (4.2% year-over-year). Dow components have toiled to grow their sales over the last five years.

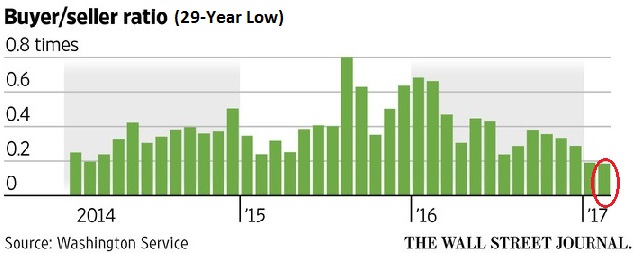

Perhaps it would be easier to dismiss concerns if executives of major corporations were buying stock for their personal portfolios. On the contrary. The ratio of insider buyers-to-sellers sits at a 29-year low.

In other words, the heads of the largest companies in the U.S. have not been this eager to unload stock shares of their respective corporations in nearly three decades. Still, they’ve shown little desire to scale back on borrowing to finance the acquisition of those very same stock shares in what is commonly referred to as “buybacks.”

Not surprisingly, then, executives remain willing to transfer borrowed dollars from corporate debt holders to corporate stock shareholders as well as deplete cash. Capital expenditures to improve long-term prospects? Not so much. Executives appear to be acting on short-term stock performance hopes, though when it comes to personal wealth, those very same executives are reducing exposure.

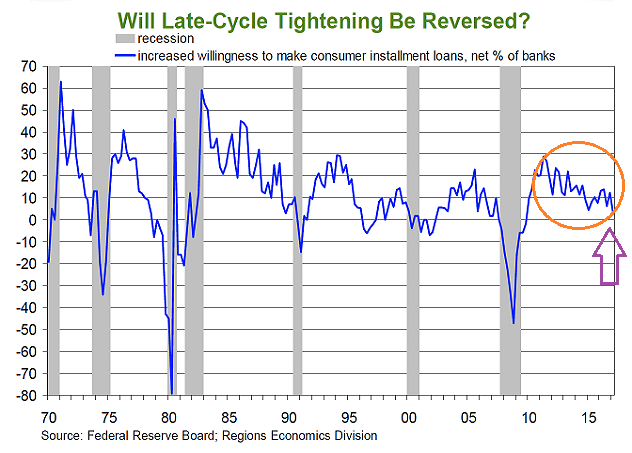

Keep in mind, not only is the Fed looking to “normalize” or “tighten,” making it a little less desirable to borrow for corporations, but banks themselves are showing a decreasing willingness to lend to consumers. That’s called access, and less people are going to get access to loans that they may covet.

Why are banks becoming more cautious with consumers? Most likely, lenders look out into the future and see repayment issues. In fact, in the Fed’s survey (courtesy of Regions Bank) of senior loan officers, lending standards are becoming more and more restrictive. Standards for credit card loans are tightening for the first time since 2010; auto loans became more restrictive by the greatest amount since 2011.

A winding down of the credit cycle would be serious. Where banks are becoming more restrictive, and where corporate revenue grows much slower than the growth of corporate debt, the Fed better be right about the economy accelerating.

From my vantage point, the economy may get a boost from fiscal stimulus, whether it be infrastructure spending, tax reform, deregulation or some combination. Yet it may not be enough. We are already sitting at some of the most elevated stock valuations in 150 years of data. The shorter-term price movement of the major benchmarks (e.g., S&P 500, Dow, etc.) might not even matter; that is, the longer-term anticipated returns for equities – 5 years, 7 years, 10 years – simply do not justify adding meaningfully to one’s risk profile. (Not if the credit cycle is abating.)

Bottom line? I am still sticking with 50% equity (down from 70%) for the bulk of my moderate clients. I am still sticking with 25% investment grade income (down from 30% widely diversified income assets). Exchange-traded trackers constitute most of the holdings, such as ishares S&P 500 (NYSE:IVV), Vanguard Mega Cap Growth (NYSE:MGK), iShares iBoxx $ Investment Grade Corporate Bond (NYSE:LQD) and iShares Intermediate Govt/Credit Bond (NYSE:GVI). Nevertheless, the 25% in cash equivalents with its negligible interest remains the prized position. You cannot buy assets lower — you cannot acquire bargains when people are fearful — unless you have the cash to do so.

Disclosure Statement: ETF Expert is a web log (“blog”) that makes the world of ETFs easier to understand. Gary Gordon, MS, CFP is the president of Pacific Park Financial, Inc., a Registered Investment Adviser with the SEC. Gary Gordon, Pacific Park Financial, Inc., and/or its clients may hold positions in the ETFs, mutual funds, and/or any investment asset mentioned above. The commentary does not constitute individualized investment advice. The opinions offered herein are not personalized recommendations to buy, sell or hold securities. At times, issuers of exchange-traded products compensate Pacific Park Financial, Inc. or its subsidiaries for advertising at the ETF Expert website. ETF Expert content is created independently of any advertising relationship.