Opinion has been extremely divided about the recent Fed rate cut. Some say it was necessary and prudent, others say it wasn't needed, and there are even those who say they're doing too little to late and rates are on their way to zero.

The bigger issue arguably is what it means for markets and the outlook. And in that arena there are likewise multiple opposing views facing off. Some might say it's a red herring, others a sign of a bear market, and others yet that it's going to extend the bull market.

In the following I attempt to address and add clarity to these issues with the cold truth of charts and indicators. I'll certainly let you know what I think, but in the end the charts will to a certain extent speak for themselves...

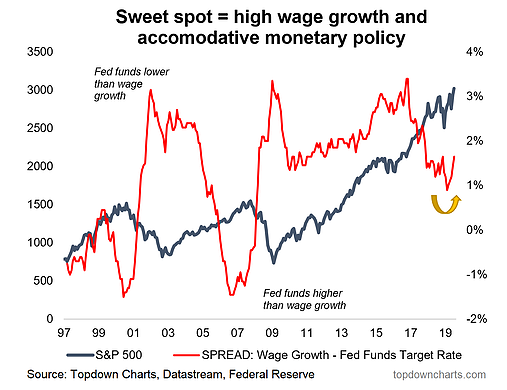

The "Sweet Spot Indicator" and the S&P 500: this weird indicator is one of my own - it takes the Fed funds rate and uses wage growth to basically contextualize it. It allows a simple model whereby we can form a judgement as to whether the current interest rate level is "good for stocks" or not.

Why though? First the rule of thumb is: the greater the spread between wage growth and the Fed funds rate, the better it is for equities (and the lower the spread, particularly when it goes negative, the worse it is for equities).

The economic logic is: higher wage growth is good for stocks because it means greater discretionary income and savings (funds that can be invested) and greater confidence (and thus willingness to take risks and deploy optimism). Meanwhile lower interest rates tend to be stimulatory for the economy (make borrowing and capex cheaper/more attractive), and tend to increase the opportunity cost of holding cash vs riskier yet higher expected return assets like stocks. So the indicator captures the signal from both of those angles, and it stands to reason that a higher rate of wage growth relative to the Fed funds rate reflects more of that good stuff in action.

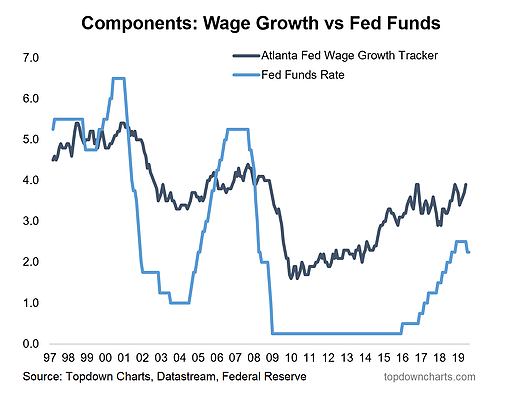

The components: specifically, what I have used is the Fed funds target rate and the Atlanta Fed wage growth tracker. The chart below shows the evolution of the two series. Most readers by now will probably realize that for rate cuts to be bullish for stocks, wage growth will need to hold up and/or accelerate (i.e. *not collapse*).

In fairness, that is an area of fundamental uncertainty. But I will say that my indicators show the U.S. labor market is still running with very tight capacity, so while wage growth is obviously going to slow down if the economy rolls over, it's fair to say there is upside risk to wage growth if a positive or even benign economic growth environment prevails.

What were you expecting?

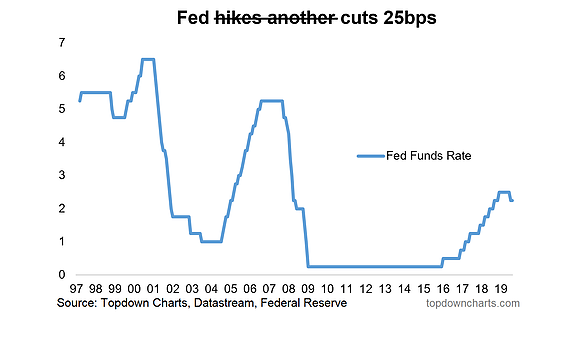

So what's up with the rate cut anyway? Here is where we start looking at the controversy and combat around the reasons and sensibility of the rate cut. It was a clear and distinct pivot from the path they were on and the path most people thought they were on. But I have a couple of charts which I think will add some robust fodder for thought.

Why did the Fed cut rates anyway?

As I mentioned, there are still plenty of signs the U.S. economy is doing alright, and indeed, the second chart in this article shows plainly that wage growth looks solid. I'm going to mostly leave the politics out of this (but then in this environment we can't completely ignore them either!).

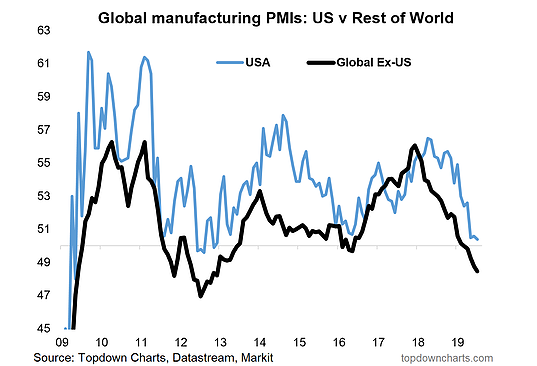

To me this chart says it all. The global manufacturing PMI *excluding the U.S.* has fallen -7.5pts since the peak in December last year; well into contractionary territory. And while the U.S. PMI has not quite crossed over to contraction, it has clearly been caught in the global economic downdrafts.

Some might say who cares? Isn't the U.S. economy dominated by consumer/services anyway? But the thing is the U.S. is not an island, and is still clearly and distinctly exposed to both the risks/shocks as well as the more mundane ebb and flow of economic activity around the world.

Indeed, recall back at the start of the hiking cycle, there was a long pause after the first hike as the global economy nearly fell off the rails (the strong dollar, weak commodities, and slowing China precipitated a near-miss global recession which in the end was only avoided due to simultaneous significant stimulus by Europe/Japan/China).

But whether you agree or not, the chart by itself provides fairly compelling evidence.

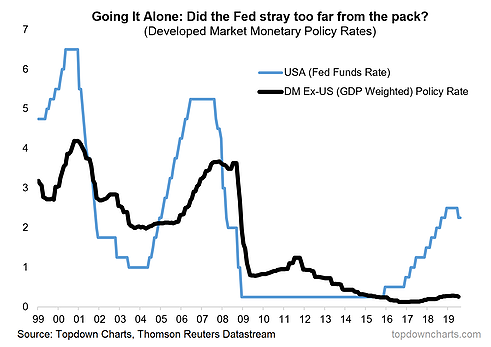

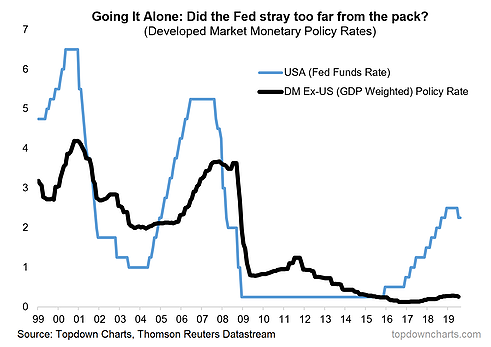

The Fed also strayed far from the pack...

In a globally integrated financial system with, for the most part, free flow of funds, the big question is how far and how long can one central bank stray from the pack? i.e. with the rest of developed markets still hugging zero, can the Fed really even get away with such substantial monetary policy tightening?

History seems to say no, and intuitively there would seem to be limits. So maybe this is just the inevitable clawing of the crab back down into the bucket.

Global monetary policy path pivoting - was 2018 a policy mistake?

It shouldn't be lost that 2018 saw one of the most substantial and simultaneous tightenings of monetary policy in almost a decade. Indeed, the extent to which central banks around the world rushed to the easing exits is relatively rare.

When you add that to the "trade policy tightening" that has gone on over the last couple of years and even heated up again recently, it's little wonder that the global growth pulse has been wavering. In effect an artificially induced, yet real, slowdown is the key driver of the global (let alone U.S.) policy pivot.

The chart below shows the net-number of central banks cutting vs hiking interest rates. The global policy pivot is on clear display here.

Going back to the first chart and the title of this piece, it would seem that such a pivot should be good for global equities, and all else equal I would say it is. For the most part global equities are trading on fair/cheap valuations (with some notable exceptions), and typically a combination of cheap valuations and easier monetary policy is a recipe for stock market success.

The missing monetary link...

If there was one thing going against that rosy prognosis, it would be this final chart. In aggregate, the Big 3 QE central banks' balance sheets are still contracting on an annual basis. The big enabler of the big bull runs of the past decade was basically in both cases (2012 and 2016) a substantial and simultaneous global policy pivot.

It's untested as to whether an interest rate policy pivot can do the trick without a balance sheet policy pivot (where basically one foot is on the brakes and another on the accelerator), so in terms of the global equity vs monetary policy puzzle, I would be watching this last piece closely.

In the end the truth will soon be revealed, and the division of opinion will be put to rest by the cold hard hand of the market. For what it's worth I've been bullish global equities since the start of the year, and I remain that way. There seem to be more moving parts lately, but I think I know what parts are the main things and I'll continue to watch them closely because market/business cycles don't last forever (even though sometimes they can be extended...).

It shouldn't be lost that 2018 saw one of the most substantial and simultaneous tightenings of monetary policy in almost a decade. Indeed, the extent to which central banks around the world rushed to the easing exits is relatively rare.

It shouldn't be lost that 2018 saw one of the most substantial and simultaneous tightenings of monetary policy in almost a decade. Indeed, the extent to which central banks around the world rushed to the easing exits is relatively rare.

It shouldn't be lost that 2018 saw one of the most substantial and simultaneous tightenings of monetary policy in almost a decade. Indeed, the extent to which central banks around the world rushed to the easing exits is relatively rare.

It shouldn't be lost that 2018 saw one of the most substantial and simultaneous tightenings of monetary policy in almost a decade. Indeed, the extent to which central banks around the world rushed to the easing exits is relatively rare.

It shouldn't be lost that 2018 saw one of the most substantial and simultaneous tightenings of monetary policy in almost a decade. Indeed, the extent to which central banks around the world rushed to the easing exits is relatively rare.