Fed watchers review each statement from the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) with a fine-tooth comb in order to suss out even the most miniscule changes. This time the policy fluctuations were easy to find—the biggest change jumps right out at you.

As always, the FOMC will continue to monitor incoming information on the economic outlook. But in Wednesday’s statement, the Fed cut the phrase “and will act as appropriate to sustain the expansion.”

No more. The committee is done acting. Now it will use all that incoming data to “assess the path of the target range for the Federal funds rate.” As far as the Fed is concerned, current monetary policy is “appropriate.”

Yesterday, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell made it clear in the press conference following the meeting that the central bank is now going back to the patient stance it had adopted at the beginning of the year, before it cut the benchmark rate by a quarter-point in three successive meetings, including the one Wednesday.

No amount of badgering from the press corps, which desperately wanted to pin down the chairman on what the future will bring, could budge him from his view that the best course of action right now was no action. Powell noted that some of the risks to the global economy have subsided.

There is now reason to hope China and the U.S. will come to some sort of accord that will ease trade tensions. Also, the risk of a no-deal Brexit seems to have been eliminated. “There’s plenty of risk left,” Powell acknowledged, but the economy has proven itself to be resilient.

So what kind of risks would prompt the Fed to reduce rates further? Or would continued growth inspire the Fed to reverse the rate cuts and start raising them again?

Tsk, tsk, Powell said in response to the questions. It’s not the economy that triggers rate moves, but inflation. “So I think we would need to see a really significant move up in inflation that’s persistent before we would consider raising rates to address inflation concerns,” he said.

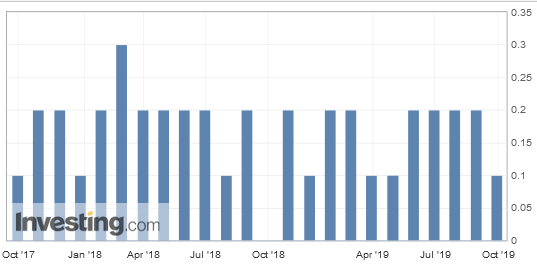

Given that inflation using the personal consumption expenditure measure preferred by the Fed was only 1.4% over the 12 months through August, it seems unlikely the “symmetric” 2% threshold—that is, 2% and then some months of overshooting before concern set it—would be crossed.

Fed policymakers, of course, are still hoping against hope that inflation really will head in that direction. But don’t hold your breath.

It was, in fact, a fairly dull press conference, with the main event a foregone conclusion telegraphed well in advance. Once the last shred of uncertainty about a third rate cut was removed and inflation was cited as the only possible reason to raise rates again, investors pushed up the S&P 500 to a new record high.

There were two dissents from FOMC voting members, as Eric Rosengren and Esther George, heads of the Boston and Kansas City regional banks respectively, didn’t like the rate cut in September and probably like this cut to 1.50-1.75 even less.

There is one more FOMC meeting this year, December 10-11, but barring dramatic economic developments there won’t be any changes in monetary policy. That meeting, however, will be accompanied by the economic projections on growth and interest rates from the 17 FOMC members and will be closely scrutinized for hints about what lies ahead in 2020.