While it is true that prices are still rising at above-average rates in some parts of the US economy, this should be expected. In some parts of the economy, it takes longer than in others for demand and supply to respond to changing monetary conditions. That central bankers choose to focus on these slower-to-respond sectors is a problem we’ve addressed many times in the past. Our purpose today is to highlight some signs that monetary tightness is taking a substantial toll.

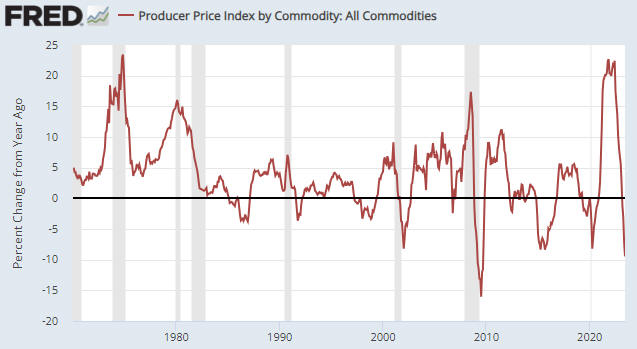

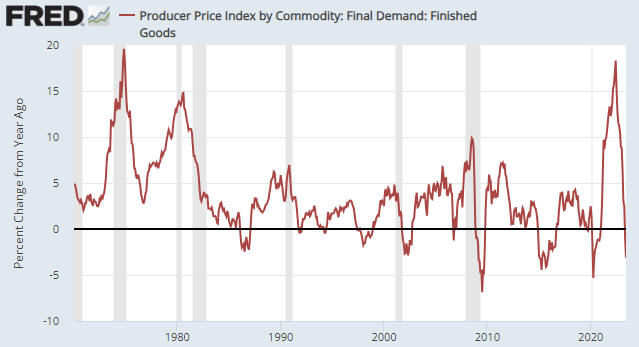

Commodity prices tend to lead producer prices for finished goods, and producer prices for finished goods tend to lead consumer prices both up and down. Therefore, the cyclical “inflation” up-swings and down-swings should become evident in commodity prices first and consumer prices last. In this respect, the Producer Price Index (PPI) charts displayed below and the CPI chart included in last week’s Interim Update show that the current situation is not out of the ordinary, despite the extraordinary monetary machinations of the past few years.

The following monthly chart shows that over the past 12 months, the year-over-year percentage change in the PPI for commodities has collapsed from near a 50-year high to near a 50-year low. We now see a level of ‘commodity price deflation’ since 1970 was only exceeded near the end of the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-2009.

The next chart shows the year-over-year percentage change in the Finished Goods Final Demand PPI. We also see a collapse over the past 12 months from high ‘price inflation to price deflation.’

Likely, the year-over-year rate of change in producer prices has just bottomed because an intermediate-term downward trend in the oil price kicked off in June of last year. To be clear, we doubt that prices have bottomed, but over the months ahead, they probably will decline at a slower year-over-year pace. However, the declines in producer prices that have happened to date suggest that the growth rate of the headline US CPI, which was 3.0% last month, will drop to 1% or lower within the next few months.

As an aside, there is nothing inherently wrong with falling prices, as lower prices for producers and consumers result from economic growth. The current problem is that prices are being driven all over the place by central bankers.

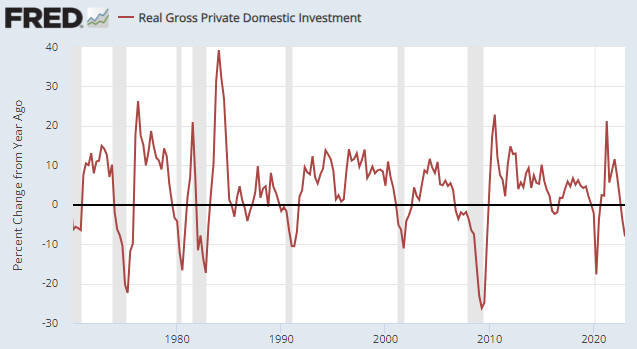

Historic ‘deflation’ in producer prices is one sign that monetary tightness is taking a substantial toll. While this price deflation could be viewed as a positive by those, not within the ranks of the directly affected producers, other signs are definitively negative. For example, the following chart shows that the year-over-year percentage change in Real Gross Private Domestic Investment (RGPDI) has plunged to a level that, since 1970, has always been associated with an economy in recession.

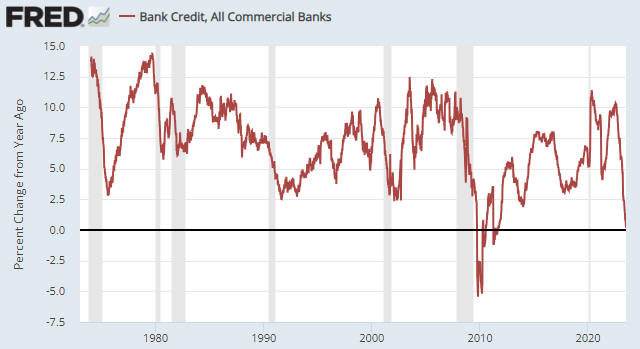

For another example, the year-over-year rate of commercial bank credit expansion has dropped to zero. As illustrated by the following chart, this is very unusual. The chart shows that in data from 1974, the annual rate of commercial bank credit growth was below 2.5% except during the 2-year aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis.

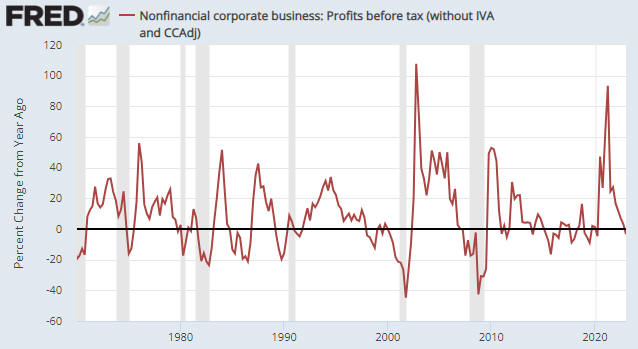

For a third example, the following chart shows that US corporate profits' annual rate of change has crashed from a stimulus-induced high during the first half of 2021 to below zero. Moreover, this chart's line will probably be much below zero after the latest quarterly earnings are reported over the next several weeks.

The above charts point to economic contraction, but the performances over the past four months of high-profile stock indices such as the S&P500 and Nasdaq 100 dominate the attention of many observers of the financial world and at present these indexes are painting a different picture. They suggest that monetary conditions are not genuinely tight and that the economy is in good shape. How is this possible?

It is partly possible because ‘liquidity’ has been injected into the financial markets despite the shrinkage in the economy-wide money supply. We note, in particular, that $514B has exited the Fed’s Reverse Repo (RRP) Facility over the past six weeks, including about $300B over just the past two weeks.

Another part of the reason is that the stock market keeps attempting to discount an about-face by the Fed. A third reason is that the senior stock averages do not represent what happened to the average stock. Related to this third reason is that money flows into index-tracking funds every month to boost the relative valuations of the stocks with the largest market capitalizations.

We end by cautioning that just because something hasn’t happened yet doesn’t mean it will happen. It’s likely that, eventually, the monetary tightening will reduce the prices of almost everything.