During the late 1990s tech boom, investors fell in love with the remarkable price appreciation of four mega-cap public corporations: Microsoft (NASDAQ:MSFT), Intel (NASDAQ:INTC), Cisco (NASDAQ:CSCO) and Dell (NYSE:DVMT). They became known as the ‘four horsemen’ for their unparalleled influence. In fact, at points in 1999 and 2000, the group accounted for as much as 55%-60% of the NASDAQ’s price movement.

Perhaps ironically, some of these hold-forever stocks began losing a bit of their appeal as dot-com mania kicked into gear. Investors began believing that the 21st century had ushered in an entirely different paradigm on how and what to invest in. Regardless of traditional metrics like profits or sales or book value, ‘New Economy’ standouts like Sun Microsystems, JDS Uniphase and EMC (NYSE:EMC) were capturing investor imagination as well as market share.

As a national talk radio personality in the late 1990s and early 2000, I cautioned listeners about the sustainability of the gains that they had come to expect. Naysayers insisted I was too bearish. Of course, most of those naysayers had never witnessed what a bear market could do. Indeed, near the very top in March of 2000, a prominent writer at the Motley Fool castigated my guidance to have a plan for getting off the surfboard when the wave ceased to be worthy of the risky ride.

Never raise cash… that was what the financial community advised the public. It did not matter that investors had been staring at the most extreme overvaluation in stock market history. It did not matter that the Oracle (NYSE:ORCL) Of Omaha, Warren Buffett, had been laughed into obscurity for his obstinate opposition to the pricing for revolutionary technologies. And it sure as heck did not matter that a young buck on terrestrial radio, yours truly, chose not to give an “all systems go” approval.

In reality, I had been defensive, downshifting form 70% stock to 50% stock. The fundamental overvaluation required me to be less aggressive. Yet I did not make a tactical shift to a genuinely bearish 33% highest quality stock allocation until key technicals broke down.

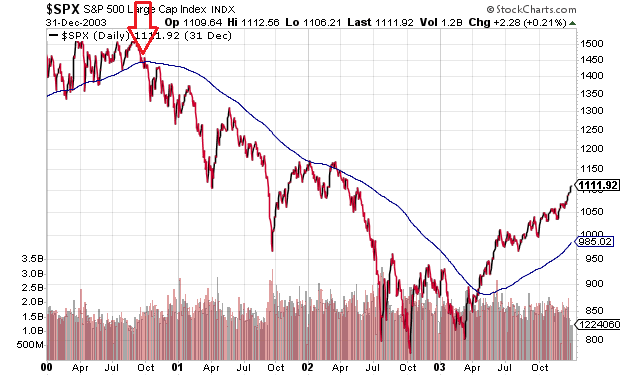

For example, when the S&P 500’s month-end closing price had finished below its 200-day moving average on September 30 (2000), the technical evidence was clearly indicating a marketplace shift toward risk aversion. I lowered my stock allocation and raised my cash allocation. Moreover, I let tens of thousands of folks know about what I was doing, helping many of them to sidestep the bulk of the tech bubble’s implosion.

Although I may have been learning to tie my own snow boots in Kindergarten during the early 1970s, I am keenly aware of the crazy love investors gave to the ‘Nifty Fifty’ stocks. As always, mainstream financial advice told investors to hold all of those stalwarts throughout their lifetimes. Even if those companies were selling at outrageous multiples of 40x, why would you sell them? General Electric (NYSE:GE), Xerox (NYSE:XRX), Sears (NASDAQ:SHLD), Polaroid, Coca-Cola (NYSE:KO) – no reason to ever sell those legends of industry.

Unfortunately, there were a few flaws with the idea of holding the ‘Nifty Fifty’ to infinity and beyond. First, even when a business appears viable for decades into the future, like a Coca-Cola or a GE, an individual stock itself is not guaranteed to remain “nifty.” Innovative new companies supplant the supposed untouchables. Second, similar to the four horsemen’s predominance in the NASDAQ’s price movement, the Nifty Fifty had been responsible for most of the price gains of the S&P 500 and most of the losses in the S&P 500’s decade-long struggles to recover capital.

It’s not that nominal dollar amounts would not still be accumulated via dividends in this period had an investor held on for 10 years. Yet why must one ignore the risk of losing so much in the first place, as though the 1973-1974 bear couldn’t have been deeper? The Nasdaq managed to lose 80% of its value this century. The Dow managed to lose 90% the previous century. Isn’t Japan still down some 50% after 28 years? Why should investors wait 17-plus years to recover purchasing power via inflation-adjusted returns, when less volatile assets show potential to outperform head-to-head and on a risk-adjusted basis?

I have put this forward before, but it is worth repeating: the 10-month simple moving average has beaten buy-n-hold over the last 90 years. Do the homework on the Ivy Portfolio yourself. Examine taxable and tax-deferred accounts. The risk-adjusted performance (e.g., Sharpe, standard deviation, etc.) is undeniable. The head-to-head may be a close call. Nevertheless, if you never wish to find your nest egg falling from $1,400,000 to $700,000, and then deciding whether to stay the proverbial course because you’ve been assured that the U.S. stock market has always recovered before, perhaps Job #1 should be to protect capital from severe downtrends.

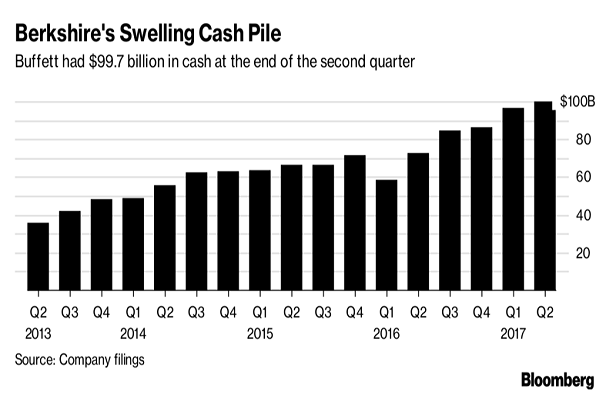

Consider Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway (NYSE:BRKa) (BRK.B). In 4 years, his cash war chest has bloated from $40 billion to $100 billion. In spite of the pile, Buffett’s team clearly does not see an opportunity to buy awesome corporations at a fair price. Additionally, he is keenly aware that the higher the price he pays, the lower the prospective future returns. Is it any surprise that the Oracle of Omaha finds the pickings rather slim?

Not only is Buffett willing to wait for attractive deals (since few exist), yet he is known for waiting patiently for sharp corrections and bears. Who would be better positioned to take advantage if stocks and/or the economy struggle mightily?

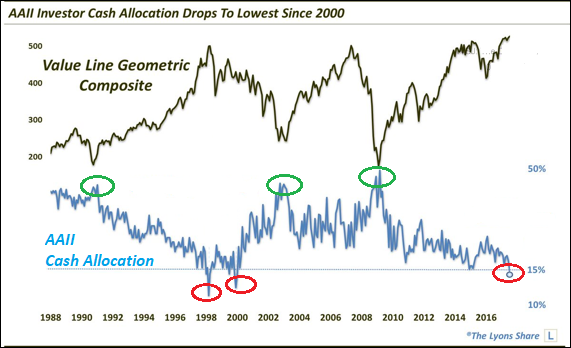

Signs of overextended bullishness may already be emerging. The American Association of Individual Investors (AAII) has not seen cash allocations as low as they are today since the Asia Currency Crisis in 1998 and the tech bubble of 2000.

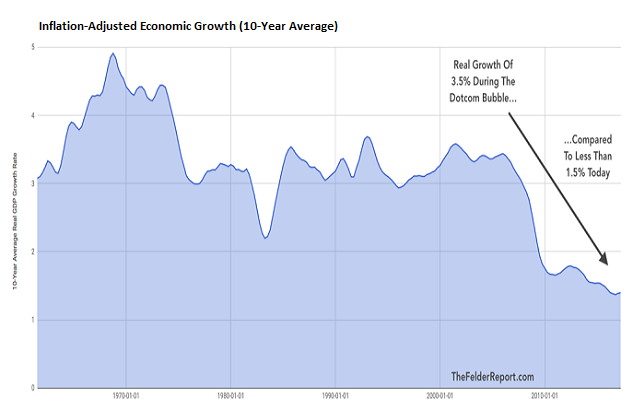

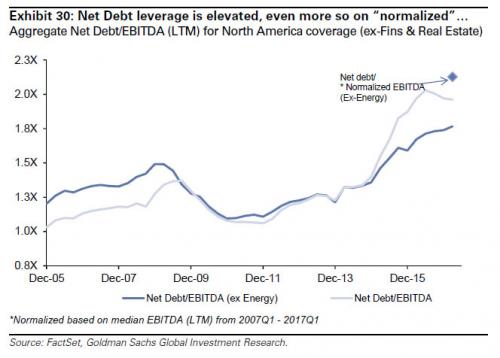

For those who may sheepishly accept the notion that the economy is humming along, they may want to get a gander at the leverage that households, government(s) and corporations have employed to achieve meager results. Consider real GDP using a 10-year average. Does anyone get the sense that our economic enhancements since the Great Recession is commensurate with taking federal government obligations from $10.5 trillion to nearly $20 trillion? Is that bang for the buck? And can we really accelerate from here?

I might have a little more confidence had corporations used the doubling of their debt levels for productive purposes. Sadly, due to interest obligations (now and in the future), coupled with the most leverage in corporate history, something may have to give. Earnings per share could suffer. Dividend growth could slow. And, in some instances, present promises abandoned.

This is not to say that the stock market will cease to grind higher. Nor would I suggest that a 5% to 10% correction would fail to become the next dip buying opportunity.

What I will say, however, is that the ‘FAANG” phenomenon smells like rookie spirit. Facebook (NASDAQ:FB), Amazon (NASDAQ:AMZN), Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL), Netflix (NASDAQ:NFLX) and Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOGL) are hardly unbeatable. They’re actually vulnerable.

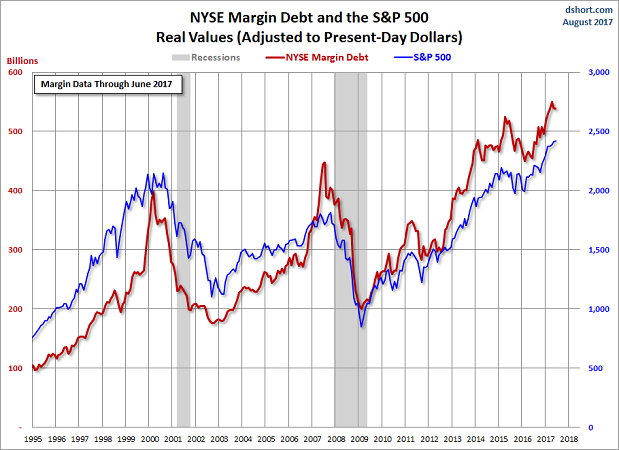

Not only did the overwhelming bulk of the Nifty Fifty reach their limits of growth, not only did three of the four horsemen hit theirs as well, but ‘FAANG’ exists at a time where leverage in the financial system has never been greater. It follows that when margin calls eventually occur, which leveraged stocks are likely to get slammed the hardest?

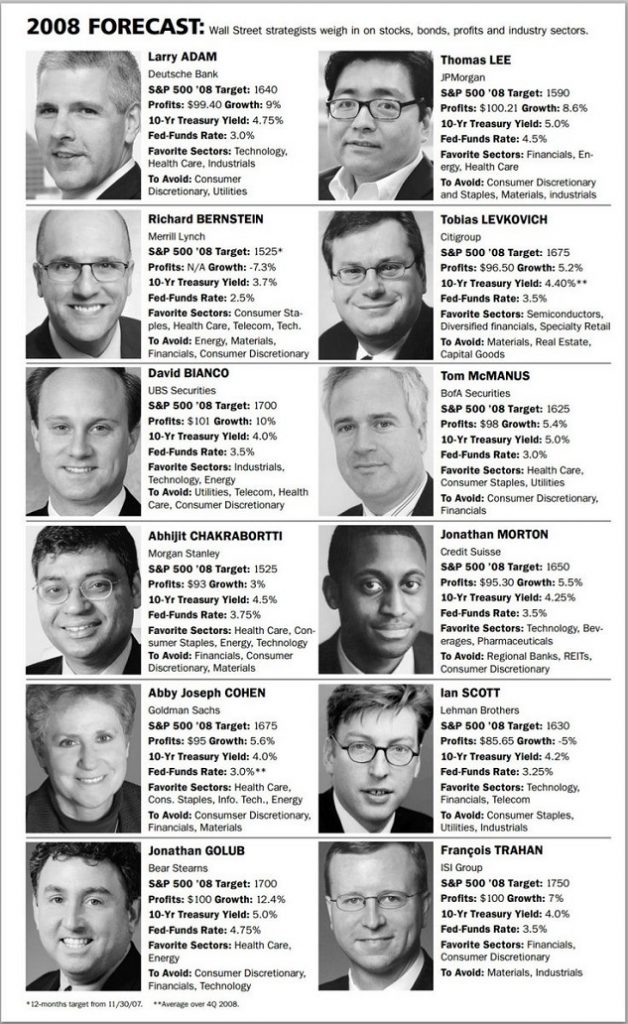

Let me close with a bit of media hype from the year of the financial crisis, 2008. There are those who will tell you that they could see the recession and the stock market sell-off coming. Some did. Investor’s Business Daily interviewed me at the very start of January in 2008, where I gave the odds of a recession at 80%. That didn’t mean I sold everything… I did not. I warned people to employ an exit strategy for reducing some exposure to the riskiest assets in their portfolios.

On the flip side, the biggest names at the biggest institutions on Wall Street had no intention (or no ability) to caution the investing public. On the contrary. Every single one of them believed that 2008 would be a banner year from earnings as well as stock prices in the S&P 500. They collectively projected stocks would finish the year in a range from 1525-1750, though it ended at 903!

In other words, do not expect Wall Street to help you with a plan to protect capital. Their job is to get you to “Buy, buy, buy!”