I recently discussed the valuation report issued by the Office of Financial Research, which contained several important statements about the risk to investors in overvalued markets. To wit:

"Markets can change rapidly and unpredictably. When these changes occur, they are sharpest and most damaging when asset valuations are at extreme highs. High valuations have important implications for expected investment returns and, potentially, for financial stability."

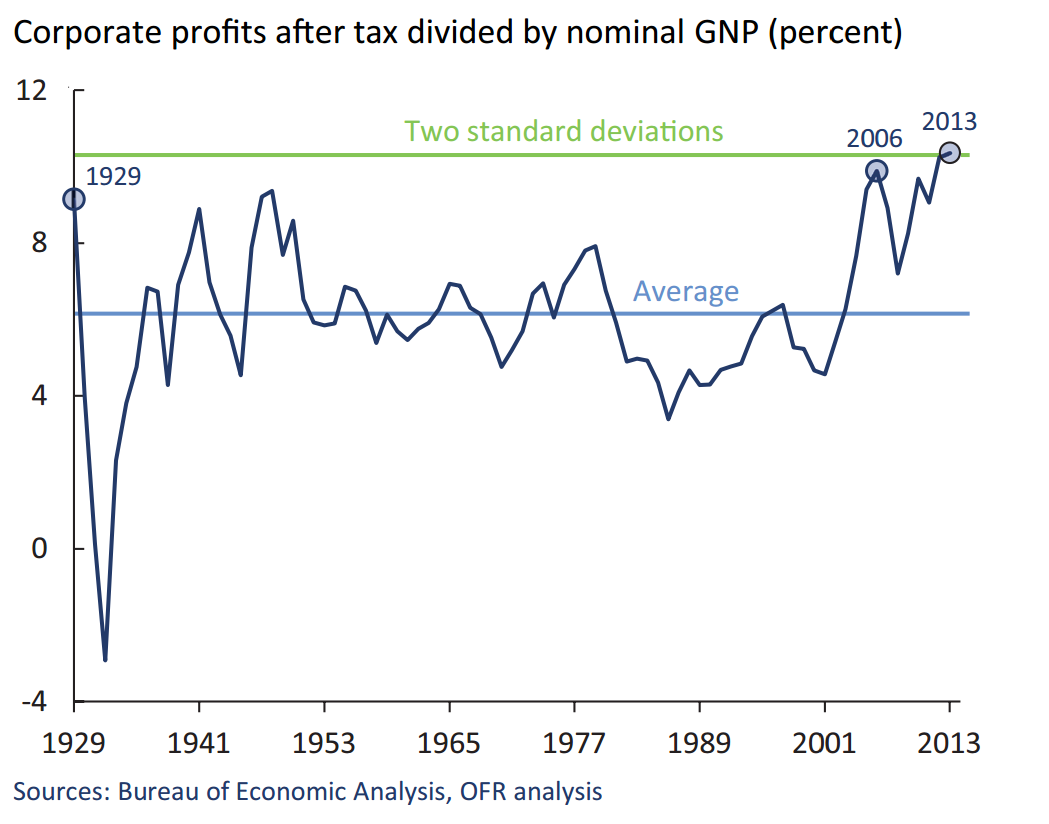

There was one particular chart that really grabbed my attention, which was the ratio of corporate profits to GDP.

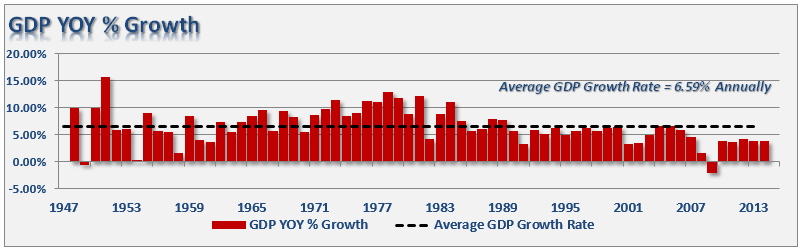

There are a couple of important points, in particular, to take away from the chart above. First, historically corporate profits floated around the long term mean of about 6%. This makes complete sense as corporate profitability is a reflection of actual economic growth which has grown by roughly the same amount as shown in the chart below.

Secondly, at two standard deviations from the long-term mean, it is clear that corporate profitability has reached historical extremes, which suggests a reversion is likely closer than not.

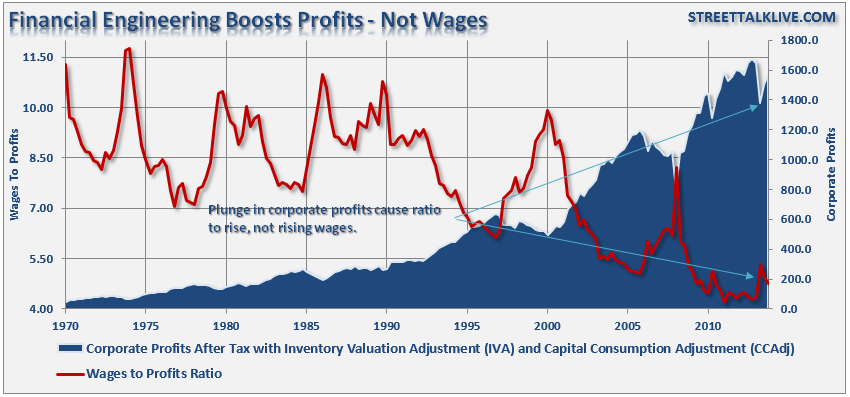

Importantly, the surge in corporate profitability has not been a function of equivalent increases in revenue growth but rather through increases in "financial engineering" from changes in accounting rules to massive share repurchases. However, profitability generated through "financial engineering" is illusory, which is why despite the surge in corporate profits, employee compensation has declined. The chart below is the ratio of wages to corporate profits.

What is important to note is that the acceleration in corporate profits has come through two primary factors; deregulation and expansive monetary policy. As noted Monday:

"Broadly speaking, systemic crises tend to be preceded by bubbles in one asset class or another. Brunnermeier and Schnabel identified four factors that accelerate the emergence of asset bubbles: expansive monetary policy, lending booms, foreign capital inflows, and financial deregulation.

They concluded that the financing of bubbles is much more relevant than the type of asset bubble, noting that 'bubbles in stocks may be just as dangerous as bubbles in real estate if financing runs through the financial system.' They also noted that the spillover effects of bubbles bursting are most severe when accompanied by a lending boom, high leverage, and liquidity mismatch of market players."

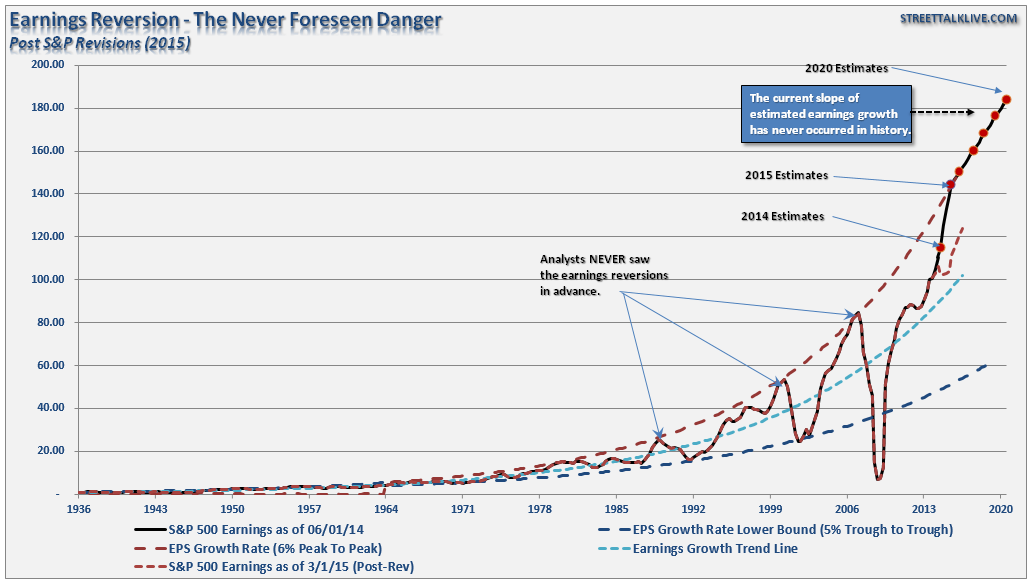

I discussed previously the growing detachment between the stock market and the "real" underlying economy. One of the areas I touched on was corporate earnings that have been elevated by an immense amount of accounting gimmickry, cost cutting, and productivity increases. The problem, as I stated, is that historically earnings have grown 6% peak-to-peak before a reversion. Notice, I said peak-to-peak. The issue is that the majority of analysts now estimate that earnings will rise unabated for the next five years.

As shown in the chart below, the dashed red line shows where earnings are currently as compared to what expectations were. Secondly, earnings have never attained the currently expected growth rate...ever.

As Jeremy Grantham once stated:

"Profit margins are probably the most mean-reverting series in finance, and if profit margins do not mean-revert, then something has gone badly wrong with capitalism. If high profits do not attract competition, there is something wrong with the system, and it is not functioning properly."

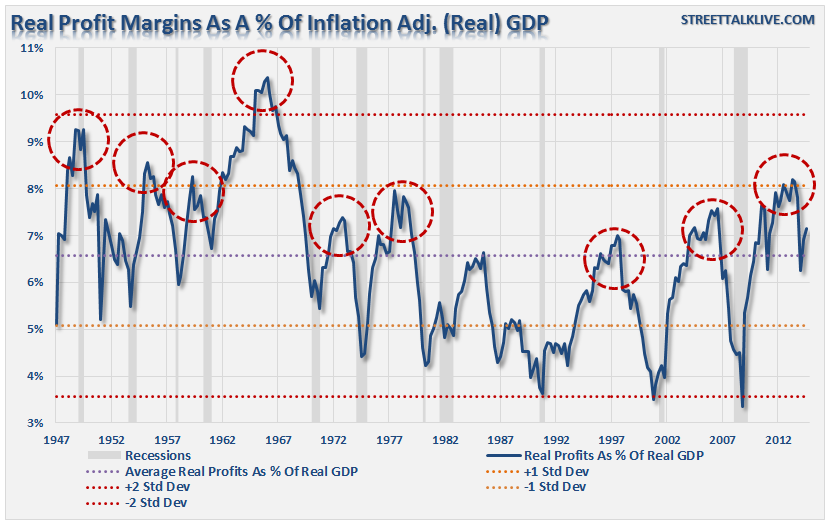

Grantham is correct. As shown, when we look at inflation-adjusted profit margins as a percentage of inflation-adjusted GDP we see a clear process of mean reverting activity over time.

Reversions occur both from peaks and troughs. Therefore, when profits-to-GDP have exceeded their long-term average to a significant degree (1 or 2 standard deviations) there has been a subsequent reversion. (Note: the chart above is real, inflation-inflation adjusted profits to real GDP as opposed to the chart by the OFR which was on a nominal basis.)

Corporate profit margins have physical constraints. Out of each dollar of revenue created there are costs such as infrastructure, R&D, wages, etc. Currently, one of the biggest beneficiaries to expanding profit margins has been the suppression of employment and wage growth and artificially suppressed interest rates that have significantly lowered borrowing costs. Should either of the issues change in the future, the impact to profit margins will likely be significant.

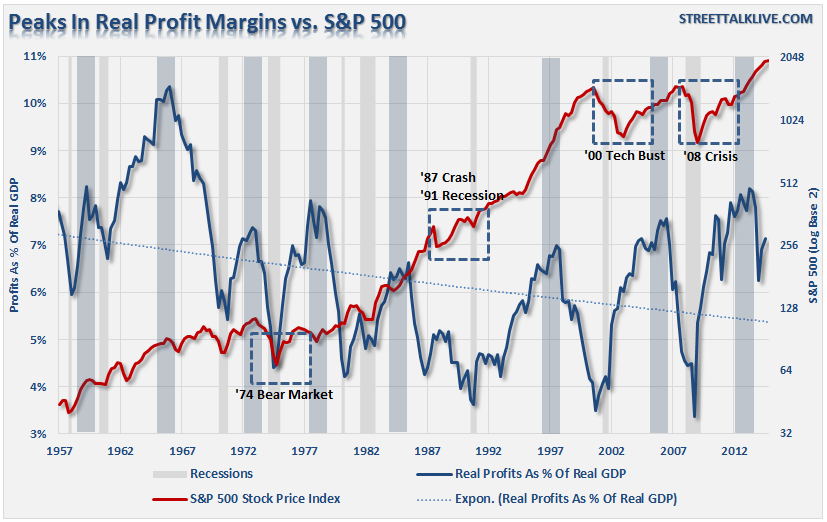

However, there is one more fascinating tale that the inflation-adjusted profits-to-GDP ratio tells us. The chart below shows the ratio overlaid against the S&P 500 index.

I have highlighted peaks in the profits-to-GDP ratio with the blue vertical bars. As you can see the peaks, and subsequent reversions, in the ratio have been a leading indicator or more severe reversions in investment markets over time. This should not be surprising as asset prices should eventually reflect the underlying reality of corporate profitability. However, since asset prices are driven by emotion, rather than logic, this accounts for the lag between the fundamentals and the realization by investors that "this time is NOT different."

As stated above, balance-sheet manipulations have been the primary factors in surging profitability. However, those actions are finite in nature and the process of manufacturing profits has cannibalized consumer incomes. Stagnant wage growth, combined with a rising cost of maintaining the current standard of living, has led to a diminishing ability to generate further sales gains in excess of population growth. This goes a long way to explain why falling gasoline prices, which does not increase real incomes, has not translated into higher retail sales.

For now, the bull market rages on as hopes of continued Central Bank stimulus dances playfully in investors heads. Eventually, the current disconnect between the economy and the markets will merge and as the OFR concluded in yesterday's report:

"Today, many market strategists see the bull market extending throughout 2015. However, Quicksilver markets can turn from tranquil to turbulent in short order. It is worth noting that in 2006 volatility was low, and companies were generating record profit margins, until the business cycle came to an abrupt halt due to events that many people had not anticipated. Although investor appetite for equities may remain robust in the near term, because of positive equity fundamentals and low yields in other asset classes, history shows high valuations carry inherent risk. Based on the preliminary analysis presented here, the financial stability implications of a market correction could be moderate due to limited liquidity transformation in the equity market. However, potential financial stability risks arising from leverage, compressed pricing of risk, interconnectedness, and complexity deserve further attention and analysis."