"If you repeat a falsehood long enough, it will eventually be accepted as fact."

In the financial markets and economics it is a common occurrence that the media and commentators will latch on to a statement that supports a cognitive bias and then repeat that statement until it is a universally accepted truth.

When such a statement becomes universally accepted and unquestioned, well, that is when I begin to question it.

One of those statements has been in regards to plunging oil prices. The majority of analysts and economists have been ratcheting up expectations for the economy and the markets on the back of lower energy costs. The argument is that lower oil prices lead to lower gasoline prices that give consumers more money to spend. The argument seems to be entirely logical since we know that roughly 80% of households in America effectively live paycheck-to-paycheck meaning they will spend, rather than save, any extra disposable income.

As an example, Steve LeVine recently wrote:

"US gasoline prices have dropped for more than 90 straight days. They now average $2.28 a gallon, which is remarkable considering that just a few months ago, some of us were routinely paying $4 and sometimes close to $5. Not so coincidentally, the US economy surged by 5% last quarter, and does not appear to be slowing down. "

If you read the statement, how could one possibly disagree with such a premise? If I spend less money at the gas pump, I obviously have more money to spend elsewhere. Right?

The problem is that the economy is a ZERO-SUM game and gasoline prices are an excellent example of the mainstream fallacy of lower oil prices.

Example:

- Gasoline Prices Fall By $1.00 Per Gallon

- Consumer Fills Up A 16 Gallon Tank Saving $16 (+16)

- Gas Station Revenue Falls By $16 For The Transaction (-16)

- End Economic Result = $0

Now, the argument is that the $16 saved by the consumer will be spent elsewhere. This is the equivalent of "rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic."

Increased consumer spending is a function of increases in INCOME, not SAVINGS. Consumers only have a finite amount of money to spend. Let's use another example:

Example:

Big John Has $100 To Spend Each Week On Retail Related Purchases

- Big John Fills Up His Truck For $60 (Used To Cost $80) (+$20)

- Big John Spends His Normal $20 Per Week On His Favorite Craft Beer

- Big John Then Spends His Additional $20 Savings On Roses For His Wife (He Makes A Smart Investment)

-------------------------------------------------

Total Spending For The Week = $100

Now, economists quickly jump on the idea that because he spent $20 on roses, there has been an additional boost to the economy. However, this is false. John may have spent his money differently this past week but here is the net effect on the economy.

Gasoline Station Revenue = (-$20)

Flower Show Revenue = +$20

----------------------------------------------------

Net Effect To Economy = $0

Graphically, we can show this by analyzing real (inflation adjusted) gasoline prices compared to retail "control purchases." I am using "control purchases" as it removes retail gasoline sales, automobiles, and building materials from the retail sales number to focus more on what consumers are buying on a regular basis.

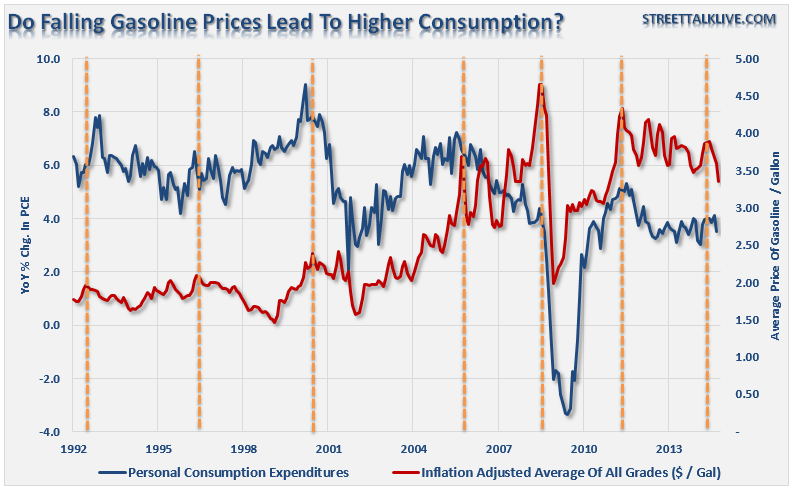

The vertical orange line shows peaks in gasoline prices that should correspond (according to mainstream consensus) to a subsequent increase in retail sales.

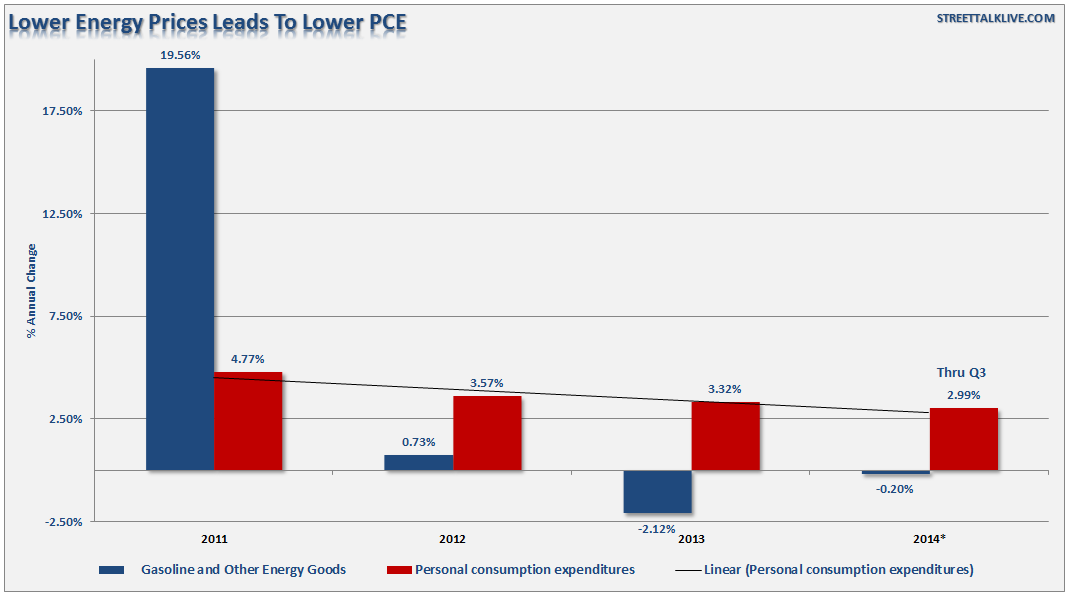

Another way to show this graphically is to look at the annual changes in Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) in aggregate as compared to the subsection of PCE spent on energy and related products. This is shown in the chart below.

While the argument that declines in energy and gasoline prices should lead to stronger consumption sounds logical, the data suggests that this is not the case.

The reason is that falling oil prices are a bigger drag on economic growth than the incremental "savings" received by the consumer.

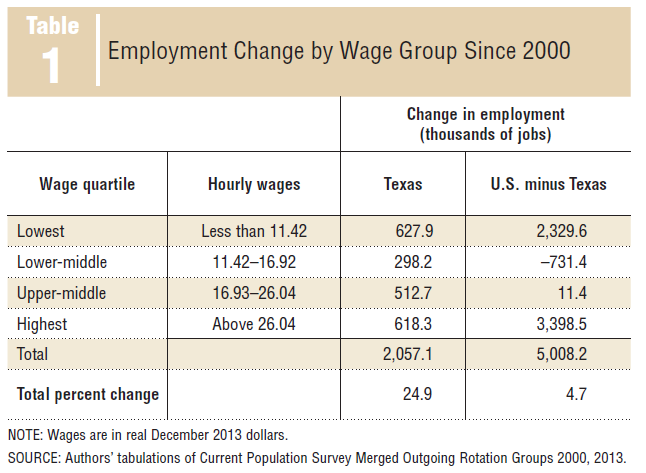

Oil and gas production make up a hefty chunk of the "mining and manufacturing" component of the employment rolls. Since 2000, when the oil price boom gained traction, Texas has comprised more than 40% of all jobs in the country according to first quarter data from the Dallas Federal Reserve.

The obvious ramification of the plunge in oil prices is that eventually the loss of revenue will lead to cuts in production, declines in capital expenditure plans (which comprises almost 1/4th of all capex expenditures in the S&P 500), freezes and/or reductions in employment, and declines in revenue and profitability.

The majority of the jobs "created" since the financial crisis have been lower wage paying jobs in retail, healthcare and other service sectors of the economy. Conversely, the jobs created within the energy space are some of the highest wage paying opportunities available in engineering, technology, accounting, legal, etc. In fact, each job created in energy related areas has had a "ripple effect" of creating 2.8 jobs elsewhere in the economy from piping to coatings, trucking and transportation, restaurants and retail.

Simply put, lower oil and gasoline prices may have a bigger detraction on the economy that the "savings" provided to consumers.

Newton's third law of motion states:

"For every action there is an equal and opposite reaction."

In any economy, nothing works in isolation. For every dollar increase that occurs in one part of the economy, there is a dollars' worth of reduction somewhere else.

I live in Houston, and the face of fear in 2015 is that oil prices remain low.