I have, on more than one occasion, discussed the surging levels of margin debt (see here and here) in the U.S. markets. These discussions were met by opposing points of view suggesting that margin debt doesn't matter.

Jesse Felder noted the same recently in his post "Why Record-High Margin Debt Should Make You More Cautious." To wit:

It's recently become popular to dismiss the record level of margin debt in the market as meaningless. Notable bloggers like Josh Brown, Barry Ritholtz and Chris Kimble have all written some sort of 'it just doesn't matter' commentary recently. Barry went so far as to call it, 'statistically bogus.' To me, this sounds like just another version of, 'it's different this time.

The problem is that margin debt DOES matter, and it potentially matters a lot. As I stated previously:

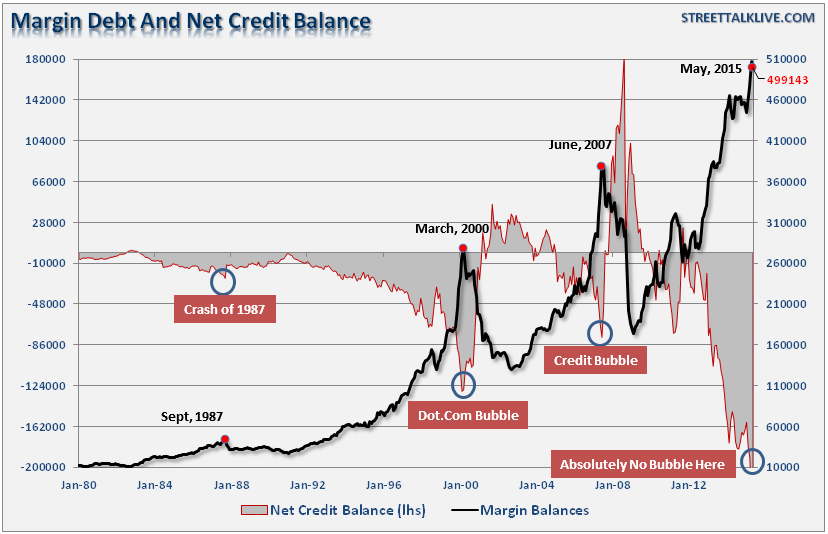

It is worth noting that when net credit balances have plunged very negative levels it has been coincident with major mean reverting events in the market.

While 'this time could certainly be different,' the reality is that leverage of this magnitude is 'gasoline waiting on a match.' When an event eventually occurs, that creates a rush to sell in the markets, the decline in prices will reach a point that triggers an initial round of margin calls. Since margin debt is a function of the value of the underlying "collateral," the forced sale of assets will reduce the value of the collateral further triggering further margin calls. Those margin calls will trigger more selling forcing more margin calls, so forth and so on.

Notice in the chart that margin debt reductions begins innocently enough before accelerating sharply to the downside.

Let me restate the obvious. Margin debt, by itself, it is inert and poses no real danger to the market. However, when combined with the correct catalyst, it will act as an accelerant to a market correction when forced liquidations fuel additional selling.

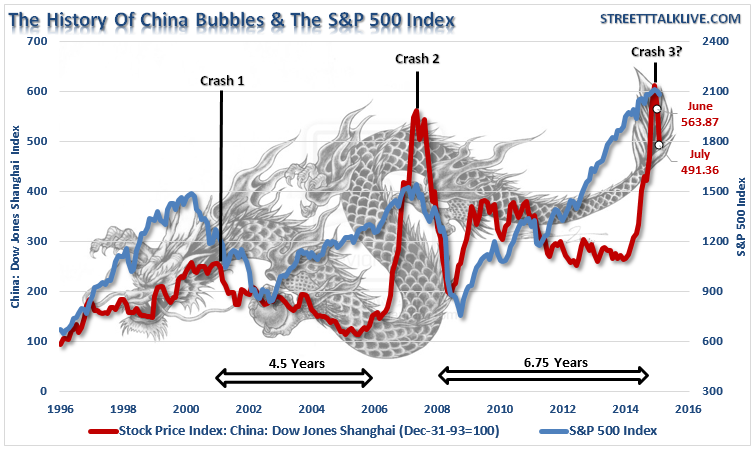

The perils of margin debt should not be readily dismissed. For a real time example of financial market leverage and consequences, one needs to look no further than the Shanghai index in China. That market is in a complete collapse as plunging prices are forcing investors to sell shares. While the Chinese government has injected liquidity, suspended trading in almost half of the listed equities and encouraged pension funds to buy securities, these actions have done little to stem the decline as investors "panic sell" in a rush to safety. That collapse, if history is any guide, is likely not done as shown in the chart below.

Also, notice the correlation between peaks in the Shanghai Index and the S&P 500. According to a recent Bloomberg article, margin debt in China reached $264 Billion in April of this year. After adjusting for the size of the two markets, is about double that of the roughly $500 billion in margin debt in the U.S.

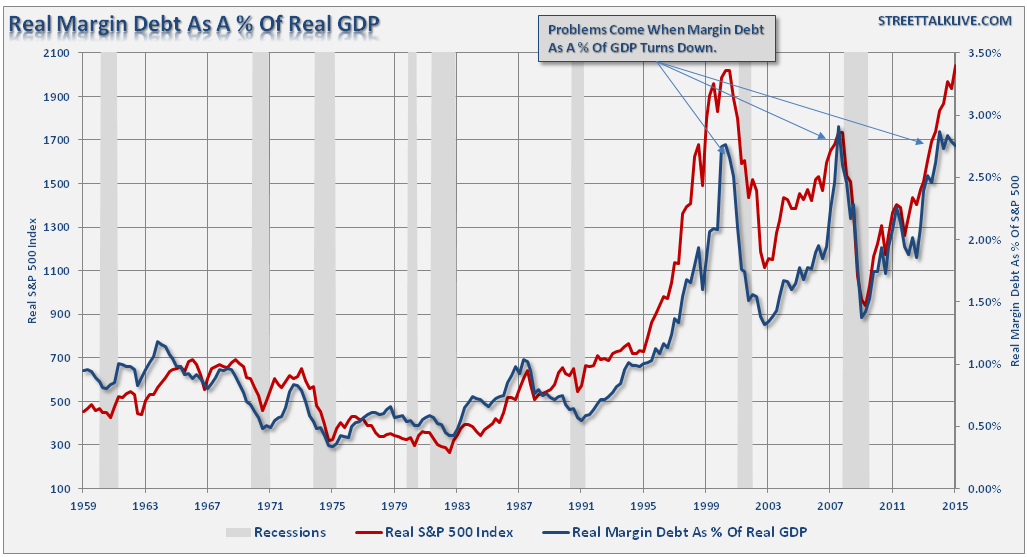

This difference in relative size was given as a prime example about how margin debt is not a problem for the U.S. However, the relative size of margin debt in the past has not been a "safety net" that investors should rely on. As shown, the level of real (inflation adjusted) margin debt as a percentage of real GDP has reached levels only witnessed at the peaks of the last two financial bubble peaks in the U.S.

While no single indicator should be relied upon as a measure to manage a portfolio, it should be well understood by now that leverage is a "double-edged sword." While rising margin debt levels provide the additional liquidity to drive stock prices higher on the way up, it also cuts deeply as prices fall.

China is clearly showing the consequences of the unwinding of leverage. Despite government actions to stem the decline, investors are finding ways to extract their capital back out of the market in fears of a repeat of the 2008 crash. It is a lesson that should be studied and learned by investors today.

Just as the Federal Reserve encouraged investors to jump into the financial markets by providing liquidity and suppressing interest rates, China also encouraged their population to do the same. Instead of taking actions to control the rise, they encouraged it. The problem is that when the "bubble" pops -- it becomes uncontrollable.

It is also worth noting that NO ONE talked of a bubble in China. Just yesterday Goldman Sachs (NYSE:GS) stated:

It's not in a bubble yet. China's government has a lot of tools to support the market.

This has been the same in the U.S. as the mainstream meme continues to be that there is "NO bubble." The problem, of course, is that bubbles have only been acknowledged in retrospect.

As investors, it is our job to analyze the data and understand the inter-relationships between various data points and our portfolios. While margin debt is but only one "bread crumb" on the trail, when combined with declining momentum, excessive deviations from long-term means, and weak economic growth, a larger picture of overall "risk" begins to emerge.

Does this mean that investors should "panic sell" immediately and run into the safety of cash? No. However, it does suggest that investors should be much more cautious about portfolio allocations and the degree of risk being undertaken as it relates to long-term investors objectives.

Jesse noted this point as well stating:

"In my view, margin debt is a very good way to 'take the market's temperature.' The extreme level of margin debt-to-GDP clearly shows investors have become 'recklessly confident.' Prudent investors should react by becoming more cautious. And, from a contrarian standpoint, the fact that popular bloggers are dismissing this idea despite its mathematical validity adds an exclamation point to that idea."

In my opinion, what is happening in China is more important to U.S. investors than the daily distractions Greece. If the Chinese government fails to stem the bursting of their bubble, it should be a lesson learned about the potential fate for U.S. markets.