In this past weekend’s missive, I said:

Following the election, the market has surged around the theme of ‘Trumponomics’ as a ‘New Hope’ as tax cuts and infrastructure spending (read massive deficit increase) will fuel earnings growth for companies, stronger economic growth, and higher asset prices. It is a tall order given the already lengthy economic recovery at hand, but like I said, it is ‘hope’ fueling the markets currently.

As you can imagine, I received quite a few comments from readers suggesting that each percentage of tax cuts will lead to surging corporate earnings and economic growth. This was a point made by Bob Pisani recently on CNBC:

The current 2017 estimate for the entire S&P 500 is roughly $131 per share. Thompson estimates that every 1 percentage point reduction in the corporate tax rate could ‘hypothetically’ add $1.31 to 2017 earnings.

So do the math: If there is a full 20 percentage point reduction in the tax rate (from 35 percent to 15 percent), that’s $1.31 x 20 = $26.20.

That implies an increase in earnings of close to 20 percent, or $157.

Fair enough.

I don’t entirely disagree considering my recent prognostication of the S&P 500 melting up to 2400 in the next few months.

However, I also want to take a step back for a moment and look at the reality of corporate tax cuts and their potential impact on the economy, and ultimately, corporate earnings.

First, of all, since estimates historically are on average 33% overestimated, such would suggest that future earnings per share will be closer to $106/share which suggest an S&P price of 2438 at 23x earnings. In line with my current estimates.

Secondly, and most importantly, changes to corporate earnings will come primarily from share buybacks and lower effective tax rates. This point should not be overlooked as long-term earnings growth, and a healthy market, is driven by changes in actual top-line revenue driven by a stronger economy and higher levels of consumption.

This is the focus of today’s analysis.

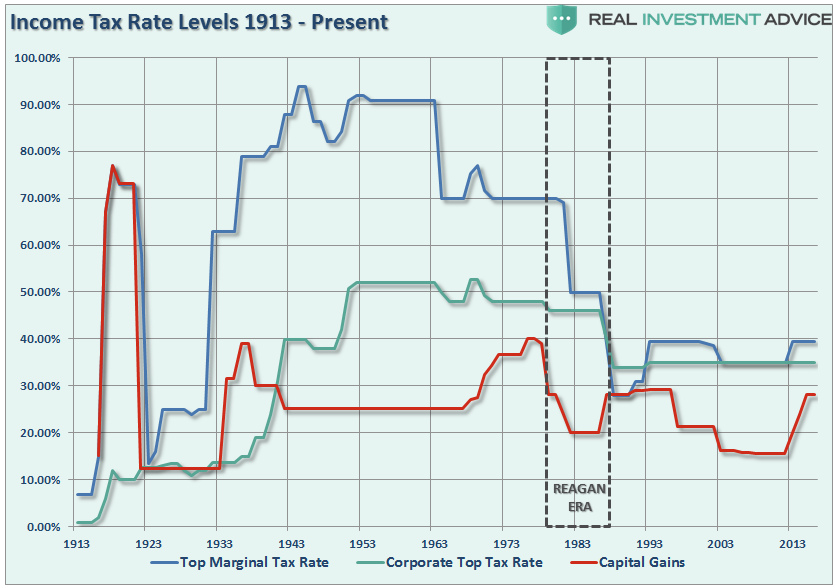

During the Reagan administration tax rates were cut in order to boost economic growth and activity along with a surge in deficit spending. The chart below shows the top tax brackets from 1913-Present.

Importantly, as has been stated, the proposed tax cut by President-elect Trump will be the largest since Ronald Reagan. However, in order to make valid assumptions on the potential impact of the tax cut on the economy, earnings and the markets, we need to review the differences between the Reagan and Trump eras. My colleague, Michael Lebowitz, recently penned the following on this exact issue.

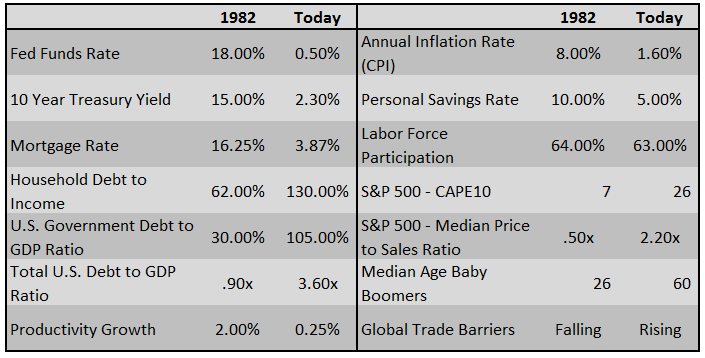

Many investors are suddenly comparing Trump’s economic policy proposals to those of Ronald Reagan. For those that deem that bullish, we remind you that the economic environment and potential growth of 1982 was vastly different than it is today. Consider the following table:

The differences between today’s economic and market environment could not be starker. The tailwinds provided by initial deregulation, consumer leveraging and declining interest rates and inflation provided huge tailwinds for corporate profitability growth.

As Michael points out, those tailwinds are now headwinds.

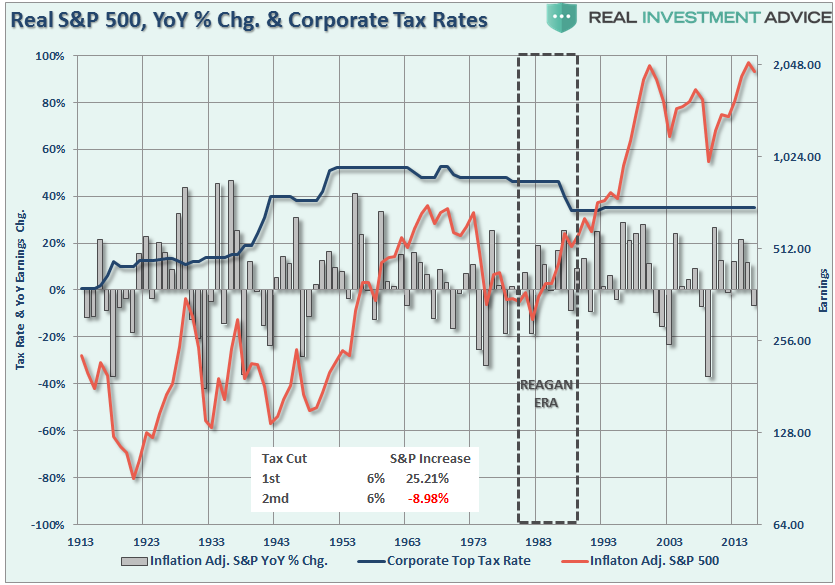

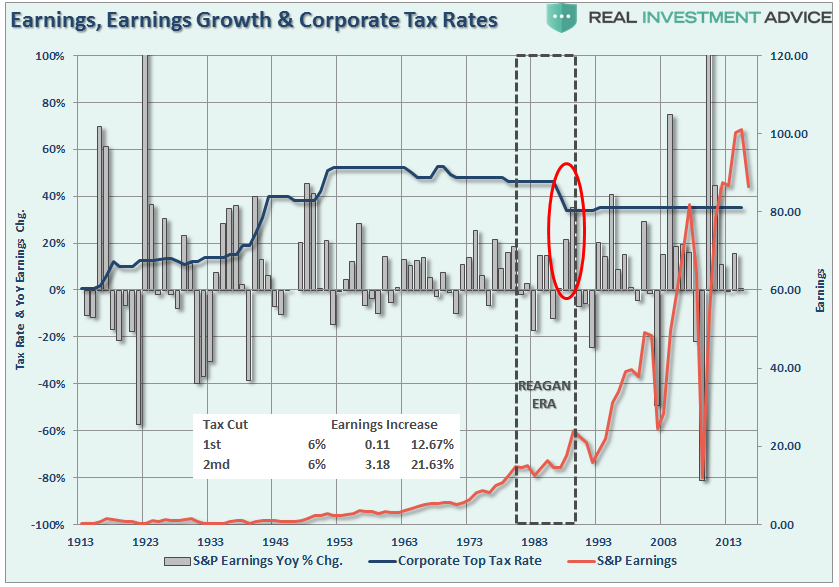

However, while Thompson’s have pulled a rather exuberant level of impact ($1.31 in earnings per 1% of tax rate reduction) a look back at the Reagan era suggests a different outcome.

The chart below shows the impact of the two rate reductions on the S&P 500 (real price) and the annualized rate of change in asset prices.

The next chart shows the actual impact to corporate earnings on an annualized basis.

In both cases, the effect was far more muted than what is currently being estimated by Wall Street analysts currently.

Furthermore, as I noted last weekend, given the primary expansion of the financial markets has been driven by monetary policy and artificially low interest rates, any benefit provided to earnings growth from lower taxes will be mitigated by reductions from changes in monetary policy.

It’s A Consumer Problem

It is also important to remember that “Revenue” is a function of consumption. Therefore, while lowering taxes is certainly beneficial to the bottom line of corporations, it is ultimately what happens at the “top line” where decisions are made to increase employment, increase production and make investments.

In other words, it remains a spending and debt problem.

Given the lack of income growth and rising costs of living, it is unlikely that Americans are actually saving more. The reality is consumers are likely saving less and may even be pushing a negative savings rate.

I know suggesting such a thing is ridiculous. However, the BEA calculates the saving rate as the difference between incomes and outlays as measured by their own assumptions for interest rates on debt, inflationary pressures on a presumed basket of goods and services and taxes. What it does not measure is what individuals are actually putting into a bank saving or investment account. In other words, the savings rate is an estimate of what is ‘likely’ to be saved each month.

However, as we can surmise, the reality for the majority of American’s is quite the opposite as the daily costs of maintaining the current standard of living absorbs any excess cash flow. This is why I repeatedly wrote early on that falling oil prices would not boost consumption and it didn’t.

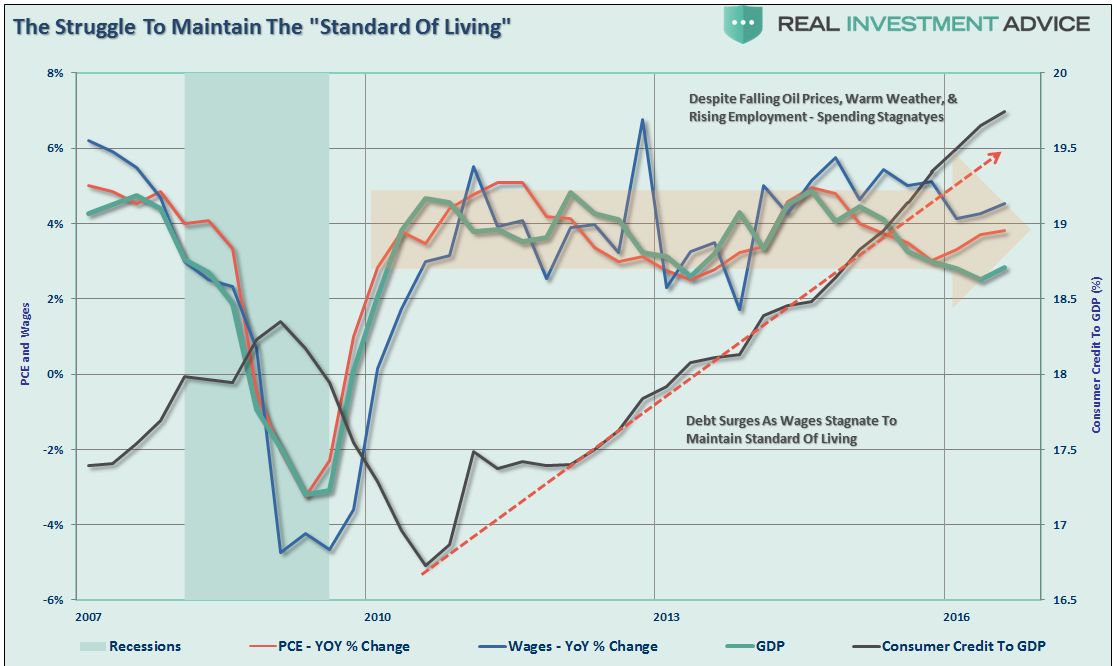

As shown in the chart below, consumer credit has surged in recent months.

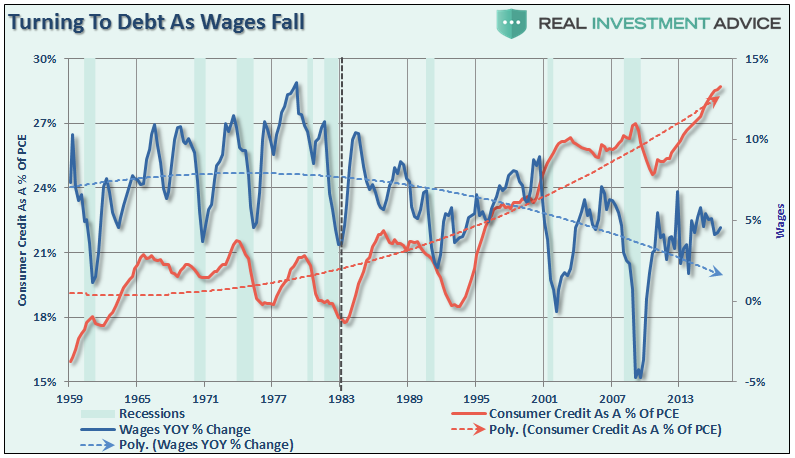

Here is another problem. While economists, media, and analysts wish to blame those “stingy consumers” for not buying more stuff, the reality is the majority of American consumers have likely reached the limits of their ability to consume. This decline in economic growth over the past 30 years has kept the average American struggling to maintain their standard of living.

As shown above, consumer credit as a percentage of total personal consumption expenditures has risen from an average of 20% prior to 1980 to almost 30% today. As wage growth continues to stagnate, the dependency on credit to foster further consumption will continue to rise. Unfortunately, as I discussed previously, this is not a good thing as it relates to economic growth in the future.

The massive indulgence in debt, what the Austrians refer to as a “credit induced boom,” has likely reached its inevitable conclusion. The unsustainable credit-sourced boom, which led to artificially stimulated borrowing, has continued to seek out ever diminishing investment opportunities.

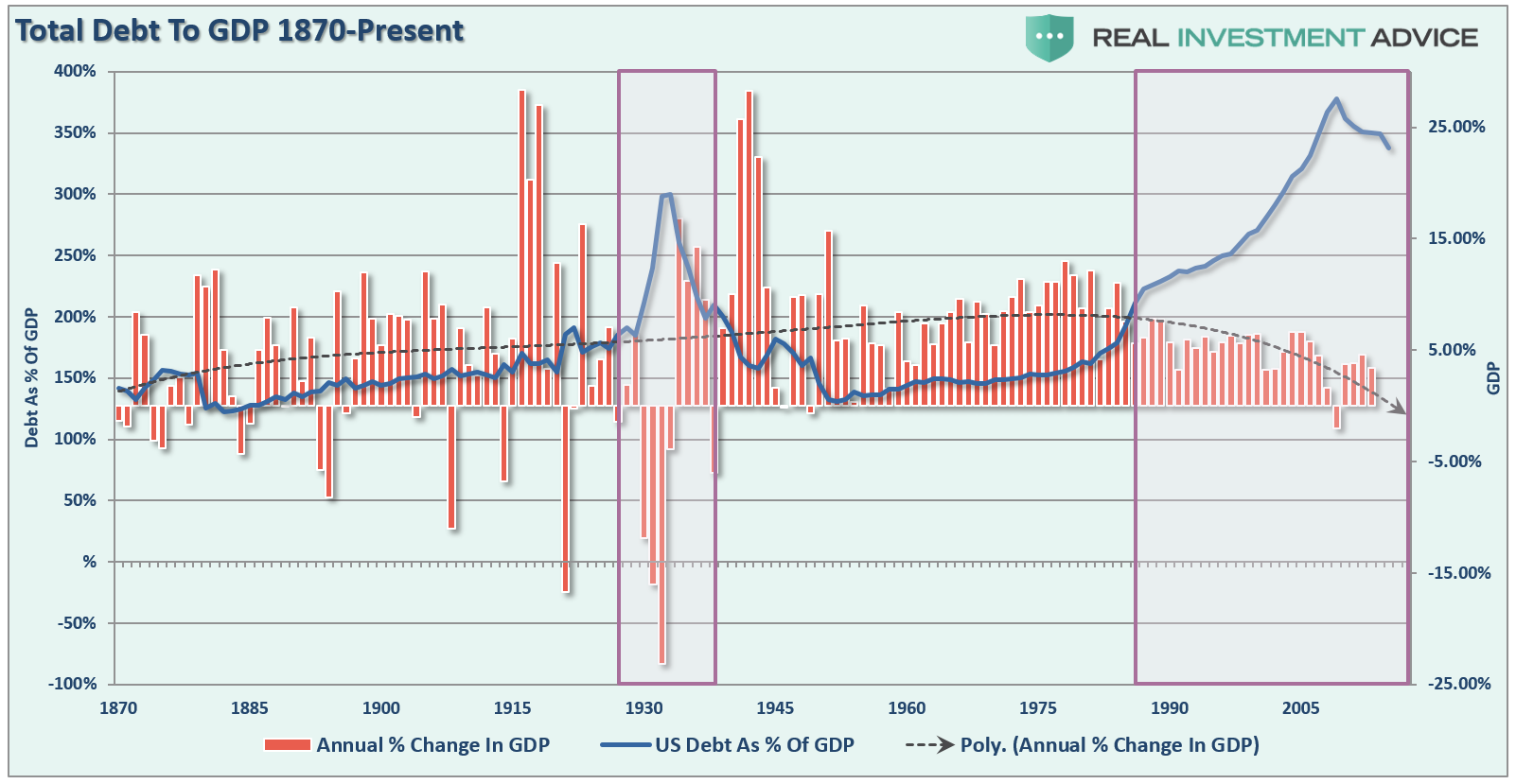

But it is not just the consumer that has leveraged itself to the point that debt service erodes economic viability, but the country as well. As shown below, there is a direct correlation between slower rates of economic growth and debt levels.

There is a logic to the Debt-to-GDP ratio increases within the historical context of two World Wars and the Great Depression. Likewise, the steadily decreasing ratio over the next 35 years enabled the tax cuts in 1964. In contrast, the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981 was followed by an 18-year secular bull market that began the following year and, paradoxically enough, by a reversal in the direction of the Debt-to-GDP ratio.

There were other epic factors that played roles in the reversal — among them the gradual transition from manufacturing to a service-based economy, the dawn of the Age of Information, and a gradual relaxation of both private and public concern about debt.

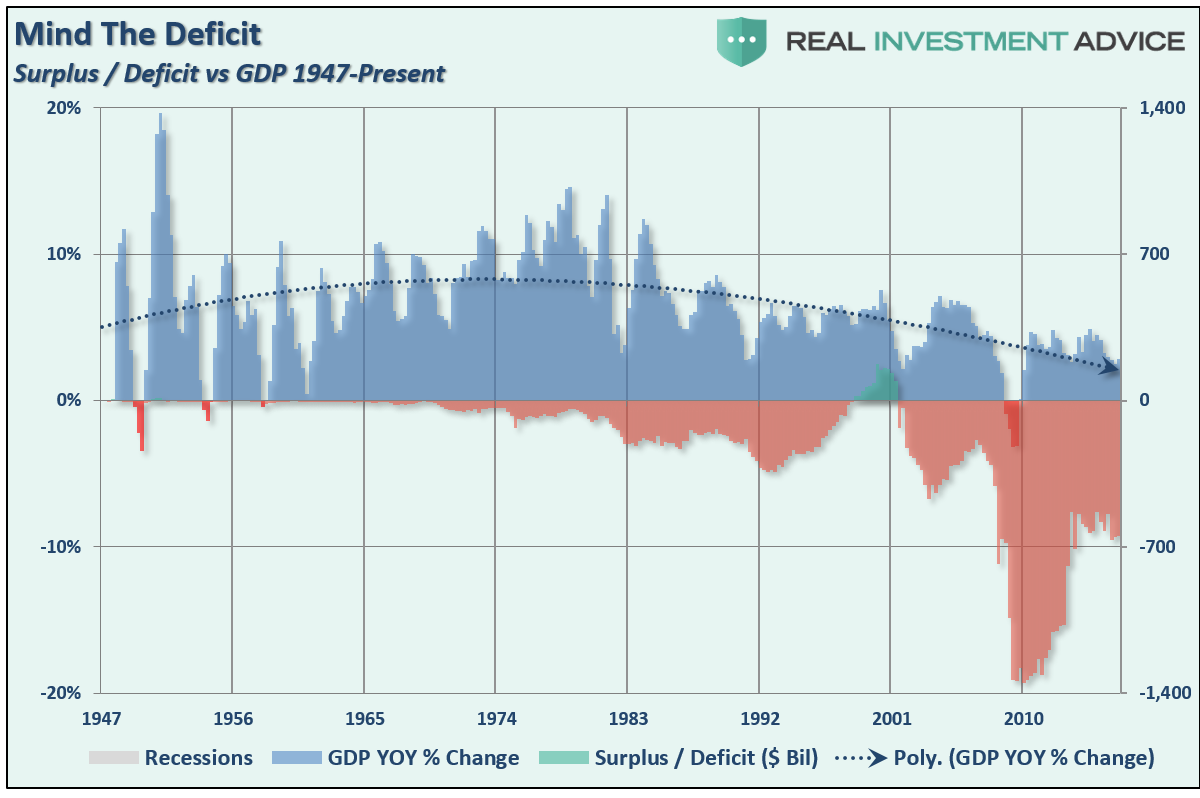

The increases in deficit spending to supplant weaker economic growth has been apparent.

While lower tax rates will certainly boost bottom line earnings, particularly as share buybacks increase from increased retention, as noted there are huge differences between the economic and debt related backdrops between today and the early 80s.

The true burden on taxpayers is government spending, because the debt requires future interest payments out of future taxes. As debt levels, and subsequently deficits, increase, economic growth is burdened by the diversion of revenue from productive investments into debt service.

This is the same problem that many households in America face today. Many families are struggling to meet the service requirements of the debt they have accumulated over the last couple of decades with the income that is available to them. They can only increase that income marginally by taking on second jobs. However, the biggest ability to service the debt at home is to reduce spending in other areas.

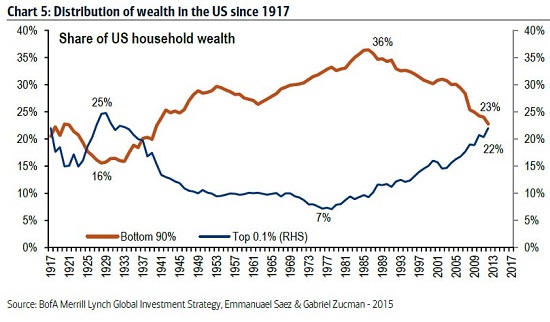

While lowering corporate tax rates will certainly help businesses potentially increase their bottom line earnings, there is a high probability that it will not “trickle down” to middle-class America.

While I am certainly hopeful for meaningful changes in tax reform, deregulation and a move back towards a middle-right political agenda, from an investment standpoint there are many economic challenges that are not policy driven.

- Demographics

- Structural employment shifts

- Technological innovations

- Globalization

- Financialization

- Global debt

These challenges will continue to weigh on economic growth, wages and standards of living into the foreseeable future. As a result, incremental tax and policy changes will have a more muted effect on the economy as well.

As Mike concluded in his missive:

As investors, we must understand the popular narrative and respect it as it is a formidable short-term force driving the market. That said, we also must understand whether there is logic and truth behind the narrative. In the late 1990’s, investors bought into the new economy narrative. By 2002, the market reminded them that the narrative was borne of greed not reality. Similarly, in the early to mid-2000’s real estate investors were lead to believe that real-estate prices never decline.

The bottom line is that one should respect the narrative and its ability to propel the market higher.

Will “Trumponomics” change the course of the U.S. economy? I certainly hope so. It will be better for us all.

However, as investors, we must understand the difference between a “narrative-driven” advance and one driven by strengthening fundamentals. The first is short-term and leads to bad outcomes. The other isn’t, and doesn’t.