The Federal Reserve reported this week that consumer credit increased by $24.5 billion in November, the largest expansion since August and one of the biggest monthly changes in the data series. Non-revolving credit was actually subdued at least as compared to what has become typical. Revolving credit, on the other hand, surged by $11 billion. That was nearly as much as the increase in March 2016, which was the third highest on record. Overall, US consumers have been using credit cards again in a way that they haven’t since the pre-crisis era.

That might propose a level of risk-taking and therefore optimism that has been missing all throughout the aftermath of the Great “Recession.” In prior cycles, rising consumer credit particularly on the revolving side has been associated with solid economic growth as recovery transitions to steadier times.

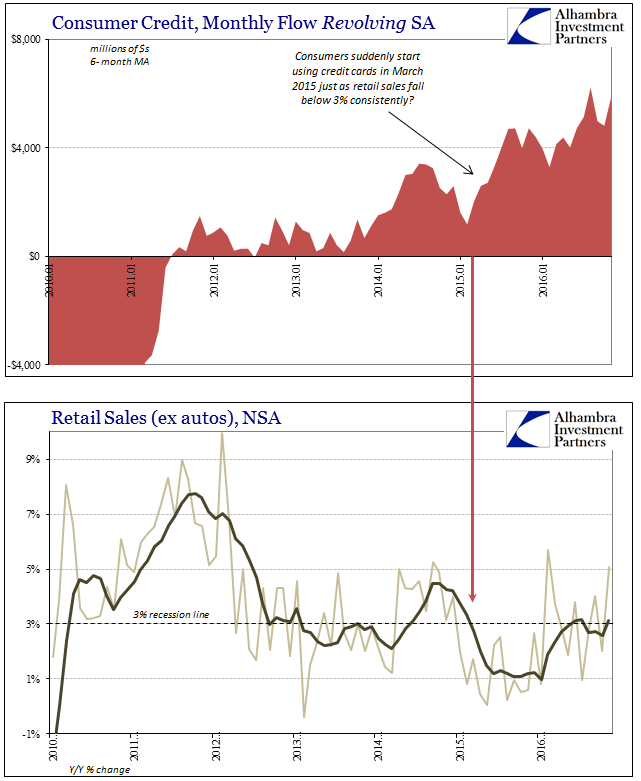

The current period is, however, nothing like prior economic cycles. Instead, there is every reason to believe that rather than risk-taking, the sustained increase in revolving credit that started in March 2015 is signal of distress. The first indication to lean in that direction is the timing itself, given that early 2015 was a period of great caution and uncertainty even though surveyed consumer confidence had risen as economists claimed recovery at every opportunity.

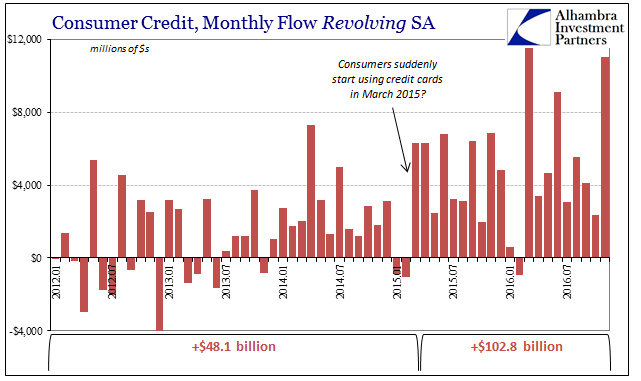

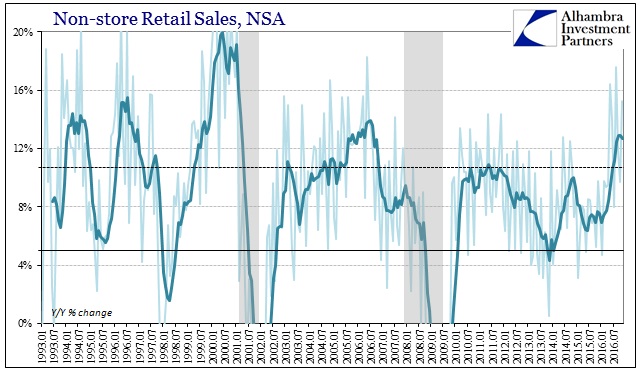

The numbers are staggering; in the 38 months from the start of 2012 (and the arrival of the slowdown) thru February 2015, consumers added just over $48 billion to their debt balances. In just the 21 months March 2015 thru November 2016, balances ballooned by an astounding $103 billion. During that time, retail sales decelerated toward some of the worst growth rates in the entire data series. Though retail sales in 2016 were better than in 2015, that really isn’t much of a comparison or change.

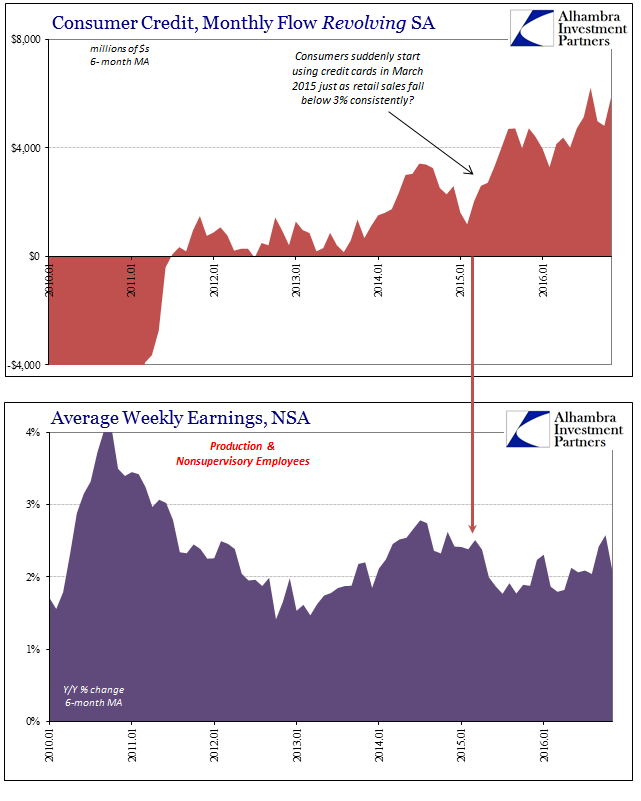

Perhaps more telling is the comparison of revolving consumer credit to the labor statistics, starting with average weekly earnings. Earnings had been accelerating, somewhat, in 2014 until abruptly decelerating right when revolving credit took off.

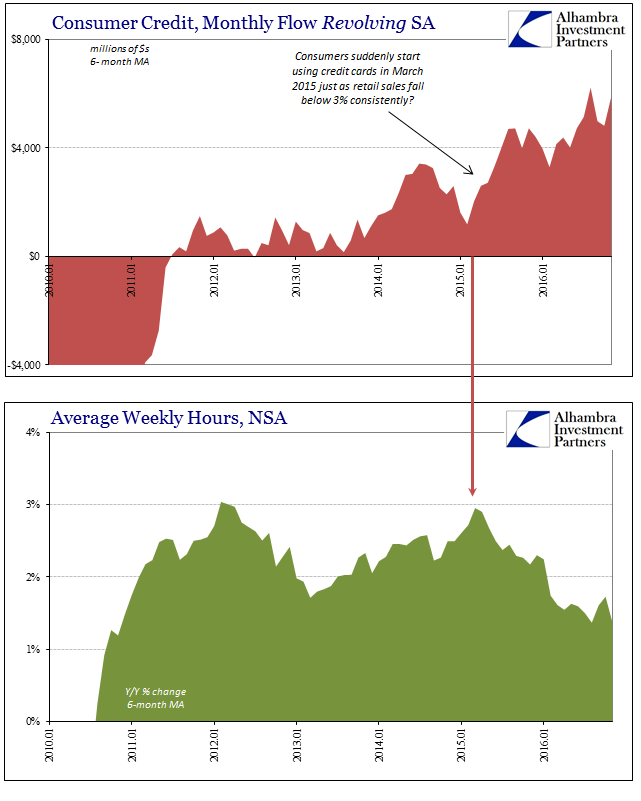

The reason for the shift in earnings was the sudden shift in labor utilization at the outset of the “rising dollar” period. Comparing the labor market as suggested by average hours worked, the almost perfectly inverse relationship is strongly persuasive.

The deceleration in hours, perhaps more so than in earnings, represented a destabilization in the labor market that isn’t very well represented in the headline Establishment Survey figures, and left completely out of the unemployment rate. If consumers were not just perceiving such a downshift and weakness but actually experiencing it, and therefore reacting to it, as would be suggested by lower growth in hours, it might make sense that they would turn to credit cards in increasing fashion as a subsidy, supplement, or likely in too many cases a last resort. We also have to consider the dramatic increase in online sales in 2016, which is itself very likely reflecting consumers’ necessary cost savings.

In that way, consumer credit continues to suggest and even confirm the labor market slowdown of the past few years. It is possible that card balances are entirely divorced from these economic stats, where consumers would be using them in a delayed recovery from limited deleveraging after 2008 anyway. The timing, however, would tend to suggest more than casual correlation. That would mean in yet another economic account the economy of 2016 was no better or different than 2015; and at the end of 2016 might even be somewhat worse.