In December of 2007, I offered readers insight into a predictive model for recessions. Shortly thereafter, in the first week of January 2008, Investor’s Business Daily highlighted my five-point model and its 80% probability of economic contraction.

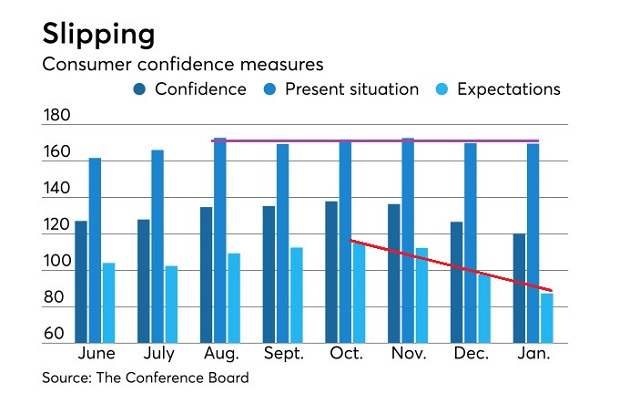

One of the key components of the model is whether or not the future expectations of consumers are falling faster than how they feel about the present economic circumstances. The Conference Board’s Present Situation Index – an assessment of current business and labor market conditions – dipped slightly, from 169.9 in December 2018 to 169.6 in January 2019. Generally speaking, however, the indicator remains stable and strong.

In contrast, the Future Expectations Index has been journeying southward. Consumers’ outlook for businesses, personal income and labor market conditions fell 10.6% from last month and 23.8% from an exuberant peak in October.

Most analysts have decided that the recent loss of consumer faith is little more than a temporary reaction to financial market volatility. Few seem to think that the decline in confidence might be foreshadowing a meaningful slowdown in economic activity.

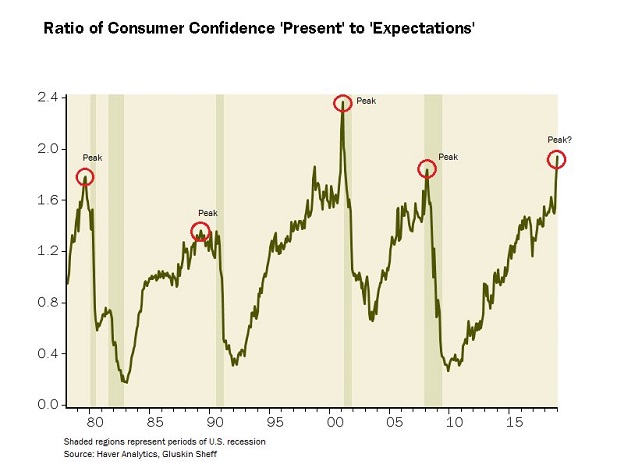

Still, one should be mindful of the historical relationship between the Conference Board’s “Present Situation Index” and the “Future Expectations Index.” In particular, peaks for the ratio between the ‘Present’ and the ‘Future’ have occurred shortly before the previous three recessions.

Perhaps the consumer trend is a minor bump in the road. On the other hand, credit spreads also provide reasons for concern.

For instance, my model suggests that 10-Year Treasuries should compensate investors by 2.5% over 3-month T-Bills. Yet the difference at this particular moment is a trifling 0.26%.

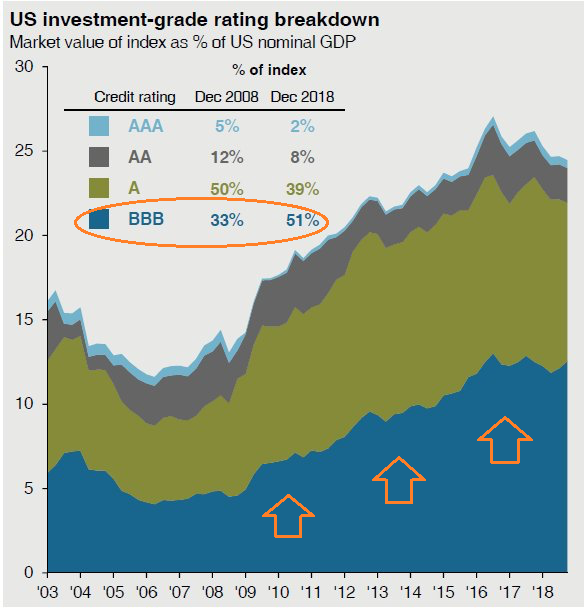

Similarly, a third feature of my model looks at whether or not the spread between corporate bonds and comparable Treasury bonds are widening over a recent period. The spread with BBBs widened modestly throughout last year, before spiking in the 4th quarter.

BofAML US Corporate BBB Index and its spread with comparable Treasuries is particularly important. For one thing, 51% of all investment grade credit is currently rated a single notch above “junk” status. Meanwhile, AAA and AA are slowly disappearing altogether.

What’s more, highly leveraged corporations could struggle mightily to pay back debts in an economic downturn. Not only would more of the income from business operations need to be redirected toward interest payments, but realistic downgrades to “junk” could call repayment itself into question.

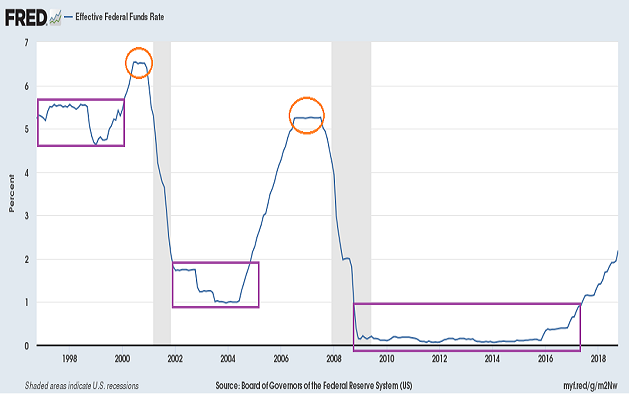

It is worth noting that the primary reason corporations have been able to manage current debt loads is ultra-low borrowing costs. If the Federal Reserve continues to exert upward pressure on interest rates – either by hiking the overnight lending rate or reducing its bloated balance sheet via quantitative tightening (QT) – companies would be forced to spend less on stock buybacks, less on capital expenditures and more on repayment of interest.

Less on stock buybacks? Couldn’t that leave more supply of stock in the marketplace at a time when price-to-earnings-per-share comparisons would appear less favorable? It sure could.

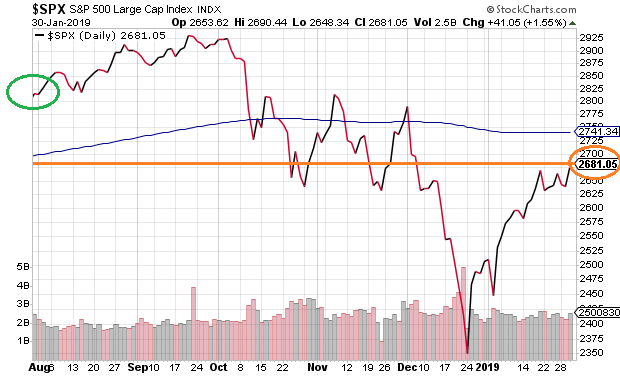

In addition to waning consumer expectations and unfavorable credit spread trends, my model looks at the S&P 500 itself. Where does it stand in comparison to six months earlier? In spite of an impressive rally since Christmas of 2018, the market is lower.

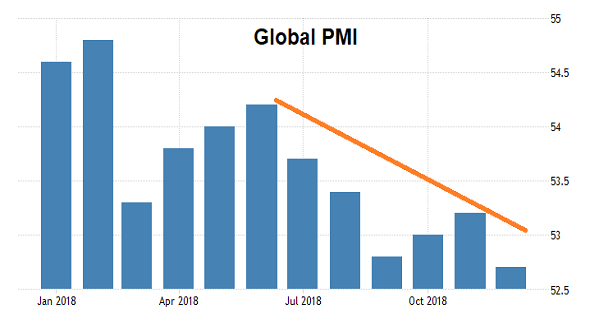

The final component of my five-point recession model (two involve different credit spreads) incorporates the Institute of Supply Management’s publication of its Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI). Why does it matter? It remains one of the Federal Reserve’s top gauges for business well-being.

The most recent “print” of 54.3 for December of 2018 is the lowest reading since December of 2016.

To be fair, anything north of 50 implies that an economy is expanding. Additionally, the sharp tick downward may be an outlier that reflected the uncertainty in government, trade and financial markets.

Still, it may be unwise to ignore the slowing that has occurred globally. The U.S. might be able to escape worldwide economic contraction, but it would be less likely to do so if foreign central banks balk at providing additional stimulus.

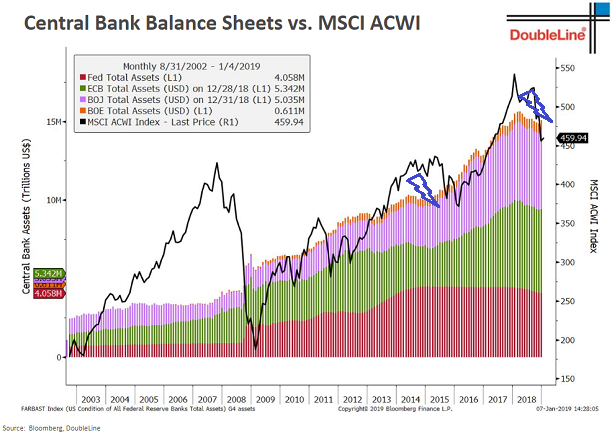

For better or worse, I believe financial markets will continue rising or falling based almost entirely on global central bank policy. Granted, the Fed left little doubt today about a shift to a neutral policy stance, capitulating from a tough-talking “we’re tightening” mode in December. Yet will enough influential players across the globe be accommodating enough to keep the stock bull alive?

When investigating the MSCI All-Country World Equity Index and ETFs like iShares MSCI ACWI (NASDAQ:ACWI), the influence of rising global central bank balance sheets in clear-cut. Specifically, since quantitative easing took off in earnest at the start of 2009, the aggregate of balance sheets as well stock prices rose through the better part of 2014. When the aggregate of balance sheets flattened in 2014-2015, the MSCI All-World Index faltered.

Once balance sheets began expanding at a rapid clip again (2015-2017), stocks around the world rocketed. And once balance sheets began to descend (2018), stocks around the globe weakened.

The Fed’s capitulation is intriguing in that it offered to be patient on what to do about interest rates as well as balance sheet reduction. Fed leadership seemed to suggest they’d even be willing to consider rate cuts and balance sheet expansion if necessary.

If the Fed and other influential central banks show an increasing willingness to expand or maintain a respective balance sheet, as oppose to taper it, risk assets like stocks could continue to reap rewards in the near-term. On the flip side, intermediate- and long-term time horizons may not be helped by central bank neutrality. (See the circles in the graphic below.)

Bottom line? The Fed better hope a recession doesn’t hit the U.S. shores. With a Fed Funds Rate at 2.25%-2.50%, and a balance sheet at roughly $4 trillion, the ammunition to fight economic contraction is extremely limited. The Fed will be forced to resort to zero percent rate policy, negative interest rate policy and trillions more in electronic dollar credit creation for asset purchases (a.k.a “QE”).

Yes, central banks can goose the markets higher. But how much higher? For how much longer?

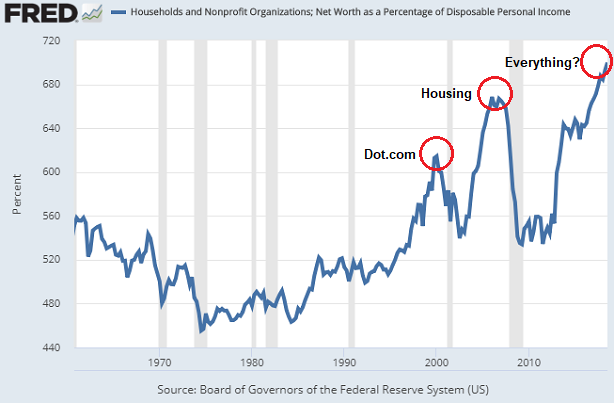

Valuation methodologies that have the strongest correlation with future returns (e.g., market-cap-to-GDP, Q Ratio, CAPE PE 10, trailing P/E, price-to-revenue P/S, etc.) place a bit of a cap on the upside. Stocks are not as insanely priced as they were in 2000, but the valuations are higher than they were in 1929 or 2007 on the above-mentioned measures.

(Note: “Forward PE guestimates” have exceptionally poor correlations with subsequent returns; they are notoriously weak valuation methods. Not sure? Revisit the “attractive” Forward PEs that led investors astray at the start of 2000 and the start of 2008.)

Similarly, homes may not be as richly valued as they were during the 2007 balloon. Yet they’re no bargain either. And that means, if you add up the big-time risk asset classes, you discover that net worth as a percentage of disposable income sits at a monstrous peak. Tread carefully.

Disclosure Statement: ETF Expert is a web log (“blog”) that makes the world of ETFs easier to understand. Gary Gordon, MS, CFP is the president of Pacific Park Financial, Inc., a Registered Investment Adviser with the SEC. Gary Gordon, Pacific Park Financial, Inc., and/or its clients may hold positions in the ETFs, mutual funds, and/or any investment asset mentioned above. The commentary does not constitute individualized investment advice. The opinions offered herein are not personalized recommendations to buy, sell or hold securities. At times, issuers of exchange-traded products compensate Pacific Park Financial, Inc. or its subsidiaries for advertising at the ETF Expert website. ETF Expert content is created independently of any advertising relationship.