Is shale production slowing? It’s a question worth asking as the U.S. rig count fell the most in nearly three years last week, and a fourth-quarter survey showed dramatic drops in oilfield equipment use and employment in Texas, southern New Mexico and North Louisiana.

Still, with U.S. crude futures trading near $55 per barrel—and projected to reach $60 and above in the near-term—there may be more incentives for domestic oil drillers to keep the spigots open, adding to OPEC’s challenges as the oil-producing cartel tries to drain an oversupplied global market.

Last week’s drop of 21 U.S. oil rigs cited by industry firm Baker Hughes justifiably jolted crude traders, accelerating gains in a market already trading in a heightened bullish mode from OPEC efforts to raise the visibility of its output cuts. The weekly rig drop was the sharpest since February 2016. Even so, what’s left—852 oil rigs—is still higher than the 747 level seen a year ago.

Lagging Indicator

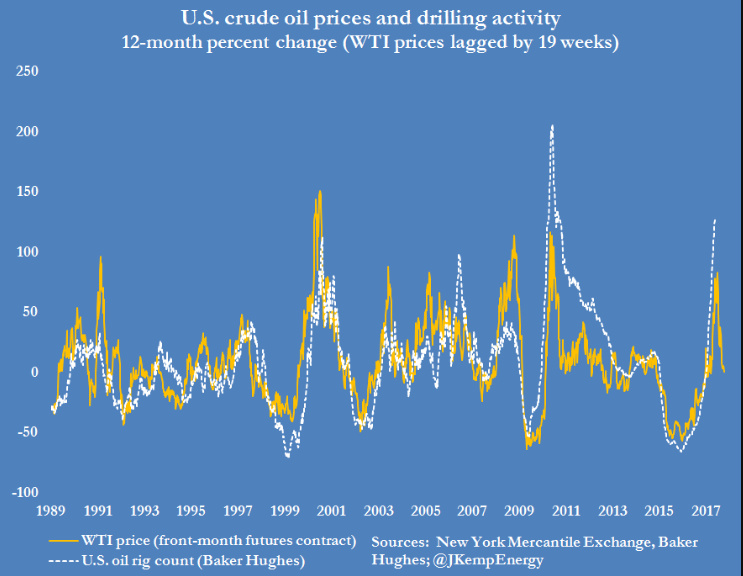

The golden rule to the oil rig count is that it’s a lagging indicator. Price changes typically lead variations in the number of rigs employed, with an average lag of between 16 and 22 weeks.

Drilling activity and futures of U.S. West Texas Intermediate are closely correlated and each exhibits a pronounced cycle.

Correlation data mined by Reuters shows that in 2014 WTI futures turned lower in the middle of June and the rig count started to fall 16 weeks later, in mid-October.

In 2016, WTI turned higher from the middle of January and the rig count began to recover 19 weeks later, from the end of May.

While each shale patch has different operating efficiencies, and there’s talk that some drillers can break even with oil as low as $30 per barrel, pricing at around $40 is generally deemed the point at which drillers may consider slowing production to await better prices.

Prices Have To Drop For Rig Declines To Trend

The current slide in the rig count comes just four weeks after WTI fell under $50 per barrel on December 17. In order for rig declines to trend, prices have to stay lower.

Since bottoming at around $42 on Christmas Eve, U.S. crude has, however, traded above $50 over the past two weeks and looks set to sustain its upward momentum toward $60.

And production is expected to grow by one million barrels this year, to reach 13 million barrels per day in 2020.

The question, therefore, is: when shale activity picks up, will U.S. drillers be able to neuter again the 1.2 million barrels or more that OPEC will be cutting in a day?

New York-based Energy Intelligence says it will be difficult to answer that question with certainty, even though firms such as Diamondback (NASDAQ:FANG), Parsley Energy (NYSE:PE) and Centennial Resource Development (NASDAQ:CDEV)—all established players in the flagship Permian shale basin—announced cuts to their 2019 capex last month.

Many Allowed Drilling Budgets To Rise Last Year

The consultancy said:

“The true test will come this year, should U.S. oil prices remain close to their current $50 level. Although publicly-traded U.S. producers routinely shelled out big sums to buy back shares rather than plow every extra dollar into higher growth, many still allowed their budgets to creep up during the year, and used the run-up in oil prices in the back half of 2018 to cover the difference.”

Asset sales could also bring cash boosts for shale companies beyond the sale of oil, allowing them to commit to spending even if oil prices don’t rise, Energy Intelligence said. The agency cited JP Morgan data showing some companies have hedged just 19 percent of their 2019 oil volumes—about 50 percent less than average. It added:

“Permian players like Halcon Resources (NYSE:HK) and Concho Resources (NYSE:CXO) have brought in millions in the past year from the sale of infrastructure to dispose of produced water, and others hold meaningful midstream assets that could rake in extra cash.”

Dallas Fed Warns Of Shale Slowdown; Goldman Says Not At Least From M&As

In a fourth-quarter survey of the Eleventh District covering Texas, southern New Mexico and North Louisiana, the Dallas Federal Reserve said the index for utilization of equipment by oilfield services firms dropped to just 1.6 points from 43 points in the fourth quarter, indicating virtually no growth at all.

The employment index in the survey, meanwhile, fell from a previous 31.7 points to 17.5, after a “moderating in both employment and work hours growth” that again suggested a slowing in shale activity, the Dallas Fed said.

But Goldman Sachs said discussions at its recent Global Energy Conference Overall showed there was “little confidence—from both investors and companies—that 2019 would be a year in which … corporate M&A would meaningfully reduce shale production in the medium term."