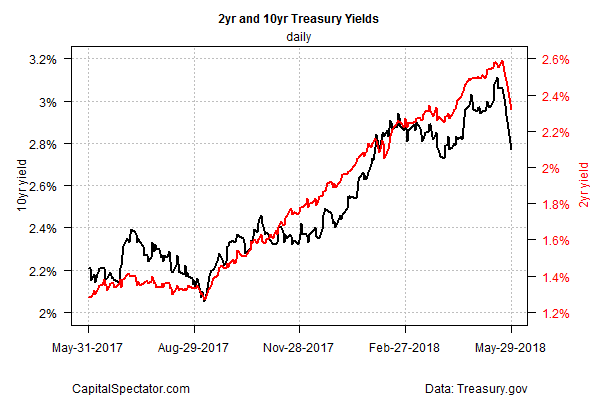

Italy’s political crisis triggered a risk-off event yesterday that sharply cut US Treasury yields. The 2-year rate fell to 2.32%, the lowest in more than a month as the benchmark 10-year yield fell to a two-month low of 2.77%.

The turmoil in Italy will probably be contained, but the potential for a wider European crisis can’t be dismissed entirely just yet. New elections in the country are likely later this year and the results will likely to resolve an impasse between anti-Eurozone populists and moderates who favor keeping Italy in the European Union. But for the near term, the Federal Reserve’s monetary tightening plans could be delayed or even derailed, depending on what happens next.

Some analysts think that the odds are low for the worst-case scenario – Italy leaves the European Union and exits the euro, a scenario that would unleash economic and political chaos in Europe and send shockwaves around the world. But that’s considered unlikely at this point.

Megan Greene, global economist at Manulife Asset Management, tells The New York Times that “I think investors are correctly looking at this as an Italy-specific risk for now.” Meanwhile, Cornerstone Macro’s Roberto Perli advised clients in a research note that the odds of Italy pulling out of the euro are no more than 15%.

A degree of calm has returned to markets in early trading New York time today. A rebound in Italian bond prices on Wednesday is an encouraging sign.

“Ultimately we think Italy stays in the club,” predicts Gordon Brown, the co-head of global portfolios at Western Asset Management in London. “Yields will settle down at a more reasonable level, but one that reflects ongoing political risk premium.”

The question is how or if the latest tumble in Treasury yields alters the Federal Reserve’s plans for staying on track with gradual but consistent interest-rate hikes? The recent slide in yields could be noise, of course, although it will be several days at the earliest for deciding if that’s a reasonable assessment.

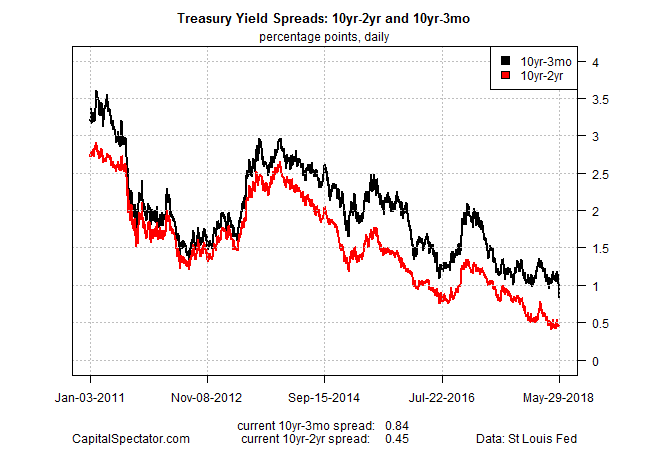

Meantime, the latest jump in demand for safe-haven Treasuries has narrowed the yield curve. Notably, the 10-year/3-month spread fell to 84 basis points on Tuesday (May 31), the lowest in more than a decade. The historical record suggests that a narrower spread reflects a rising risk of economic weakness in the near term; an inverted curve (short rates above long rates) is widely considered a forecast that a recession is near.

But several Fed officials, including Chairman Jerome Powell, have recently questioned the reliability of the Treasury yield curve as a predictor of economic weakness. The skepticism resonates, largely because the case is still weak for seeing a US recession in the immediate future.

Nonetheless, if global demand for Treasuries continues to put downward pressure on medium and long rates, the central bank may be reluctant to lift short rates and thereby create a recession warning via an inverted curve. Dismissing the yield curve’s value as a macro signal in the abstract is one thing; actively participating in a curve inversion is something else if you’re running the world’s most powerful central bank.

For now, the crowd is still pricing in high odds that the Fed will again lift rates at next month’s policy meeting. Fed funds futures this morning are pricing in an 84% probability that the target rate will increase 25-basis points to a 1.75%-to-2.0% range, based on CME data.

But as the political turmoil in Italy suggests, the Fed may not be in total control of monetary policy in globalized economy that’s still struggling to overcome the economic and financial blowback from the 2008-2009 financial crisis.

What is clear is that Europe’s political consensus on integration is a fragile beast. A new round of elections in Italy to break the current impasse will be a stress test for the European Union, with repercussions, for good or ill, that will cross the Atlantic.

US Treasury Secretery Steven Mnuchin yesterday said the US was monitoring the situation in Italy, but for now there are no signs of “any systemic impact” on US markets. But the Treasury chief’s preferences for the road ahead in Europe are firmly supportive of the status quo. “It would be better if they were to work things out within the Eurozone without making significant changes there, and certainly the Italians have the opportunity to do that.”

Meantime, investors the world over will be closely watching how the Italians choose to define that opportunity in the months ahead.