Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell, at his first press conference as the head of the central bank, announced a hike in interest rates. Tighter monetary policy was widely expected. What was surprising was Powell’s comments on the value of the Treasury yield curve as a tool for predicting the next US recession.

Responding to the last question at the press event, Powell said that “it’s true that yield curves have tended to predict recessions if you look back over many cycles.” But the near-flawless record of using an inverted curve – short rates above long rates – no longer applies in the current economic climate, he explained. History, in short, is misleading.

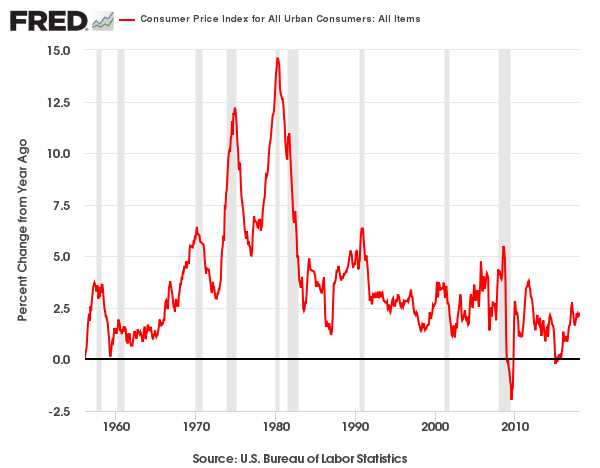

A lot of that was just situations in which inflation was allowed to get out of control and the Fed had to tighten and that put the economy into recession. That’s really not the situation we’re in now.

Powell believes that with inflation holding at relatively low levels, the Treasury yield curve is no longer a reliable signal as an early warning that a new recession is near. Many analysts are sure to disagree. Nonetheless, it’s surprising to hear a sitting Fed chair speak so clearly about a business-cycle indicator that’s been widely studied and embraced for years in the dark art/science estimating recession risk in real time.

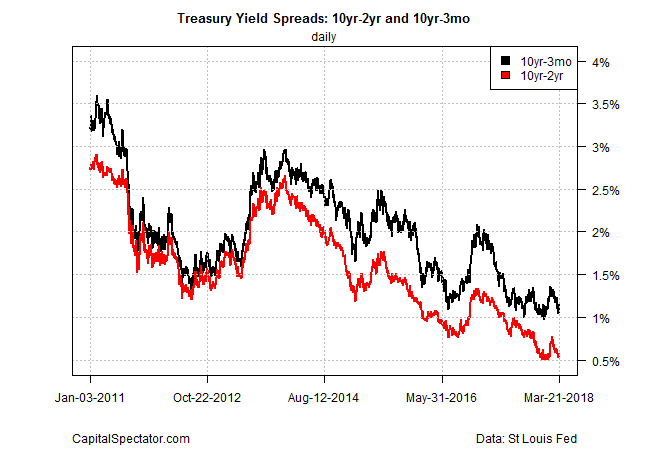

Whether you agree with Powell or not, his dismissal of the yield curve deserves attention, in part because the spread is close to the lowest level since the last recession ended. For example, difference between the 10-year rate less the 2-year rate is just 58 basis points (as of March 21), which is just slightly above the 51-basis-point mark in January, the lowest since 2007.

Economists point out that the rate spread has dipped into negative terrain just ahead of NBER-defined recessions for decades. By some, perhaps most accounts, the yield curve remains a critical indicator for deciding if a new downturn is a high-probability risk. Based on Powell’s comments, however, it’s reasonable to count the Fed chairman as a skeptic.

Powell didn’t offer any details, but his reasoning appears to be based on the idea that accelerating inflation combined with a negative yield curve is a warning sign for the economy. The implication: if inflation is relatively low and stable, a low or negative interest-rate spread doesn’t predict a recession. That scenario for inflation seems to apply to current conditions. Consumer inflation in February, for example, increased at a 2.2% year-over-year rate, or just slightly above the Fed’s 2.0% target.

Pricing pressure is still low by historical standards, but minds will differ on whether inflation is heating up by more than a trivial degree. Note that the current 2.2% annual rate of headline consumer inflation is well up from a brief run at zero and mild deflation two years ago.

The key question: if the yield curve does invert at some point in the near future, would that constitute a robust recession forecast? Using Powell’s comments as a guide, a genuine warning signal would have to be accompanied by a significant acceleration in inflation.

History certainly tells us that past recessions since the 1960s have been associated with sharply higher levels of inflation, as the chart below shows.

Does the recent jump in headline consumer inflation to just above 2% from a flat reading two years ago meet Powell’s standard? The Fed chairman doesn’t think so, or so his comments suggest. The larger question is whether the financial markets and investors agree?

For the moment, the Powell doctrine, if we can call it that, is an academic topic. The yield curve is still positive, if only modestly, inflation remains relatively tame, and the economy is growing.

If and when those conditions change for the worse, a real-world test awaits for Powell’s theory about the value of the yield curve in a low-inflation environment. But with the 10-year/2-year spread less than 60 basis points from inversion, that test may be near.