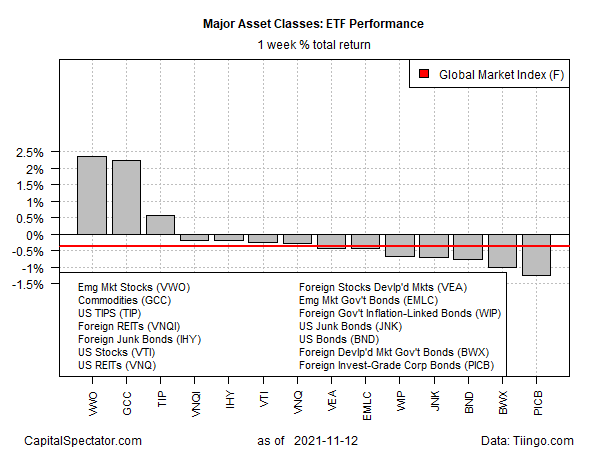

Shares in emerging markets topped returns for the major asset classes during the trading week through Nov. 15 12, based on a set of US-listed ETFs. But if interest rates are set to rise, triggered by higher inflation, the prospects for an extended rally could be short lived, or so market history suggests.

But hope springs eternal, at least for this month. Vanguard FTSE Emerging Markets Index Fund ETF Shares (NYSE:VWO) rose for a second week, gaining 2.3%—the fund’s biggest weekly jump since mid-September and the strongest gain for major asset classes.

Most markets, however, lost ground last week. The downside bias weighed on the Global Market Index (GMI.F)—an unmanaged benchmark (maintained by CapitalSpectator.com) that holds all the major asset classes (except cash) in market-value weights via ETF proxies. The benchmark fell 0.4%—the first weekly loss in six weeks.

Despite the latest rally in emerging markets shares, VWO continues to trade in a range that’s prevailed since the summer. Future gains may be limited if central banks lift interest rates to battle higher inflation.

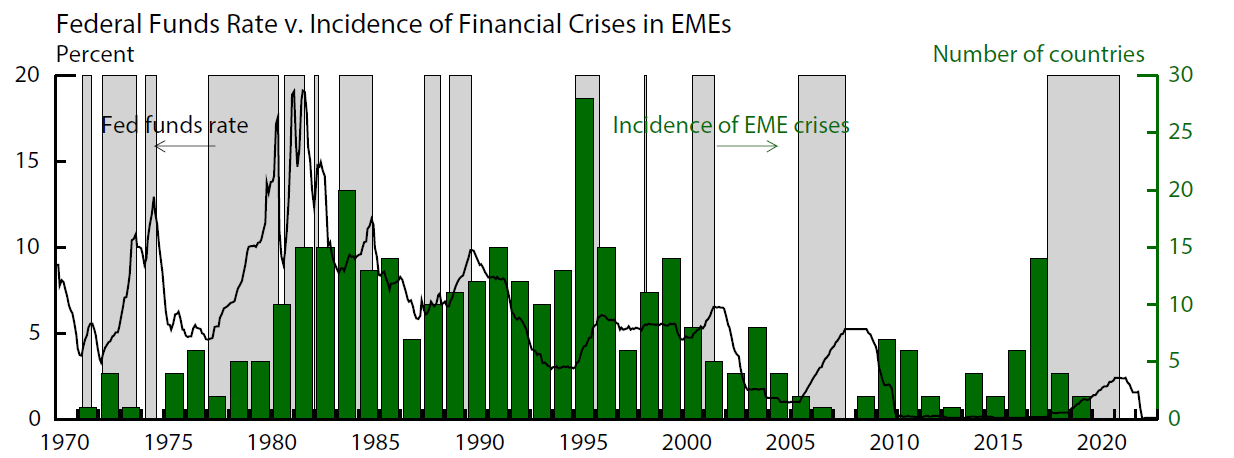

Higher rates are a headwind for stocks generally, but the risk is higher than average for emerging markets because “they increase debt burdens, trigger capital outflows, and generally cause a tightening of financial conditions that can lead to financial crises,” observes a recent Federal Reserve research note.

"As shown in Figure 1 below, the rise in the federal funds rate (the black line) during the Volcker disinflation of the early 1980s was associated with a sharp rise in the incidence of financial crises in [emerging markets economies] EMEs (the green bars). However, on other occasions, such as in the mid-2000s, EMEs weathered rising US rates with few difficulties."

The threat of higher rates should be weighed against relatively low valuations, writes Chris Dillow at Investors Chronicle:

“The ratio of MSCI’s emerging markets index to its developed world index is now at an 18-year low. You might reply that this tells us more about how expensive US equities are than about how cheap others are, but the fact is that this ratio has in the past helped to predict annual returns on emerging markets.”

He adds that “even if US interest rates do rise, they will stay very low by historic standards—low enough, perhaps, to support capital flows into emerging markets.”

The Fed paper recommends focusing on two areas to evaluate the risk of spillovers for emerging markets from US monetary policy. The first is understanding why US rates are rising:

"A rise in interest rates driven by favorable growth prospects is likely to have relatively benign effects on emerging financial markets, since the benefits of higher US GDP through increased import demand from its trading partners and increased investor confidence should mute the costs of higher rates."

By contrast, “if higher rates are driven mainly by worries about inflation or a hawkish turn in Fed policy, which we jointly describe as monetary news, this will likely be more disruptive for emerging markets.”

The second factor: local conditions in emerging markets.

“Financial conditions in economies with higher macroeconomic vulnerabilities tend to be more sensitive to a given rise in US interest rates.”

"Our findings help to explain why the rise in US Treasury yields in recent months has had fairly muted effects on financial conditions in EMEs. Despite some uptick in response to recent inflation readings, much of that rise likely owes to mounting expectations of a swift economic recovery in the United States, which should redound to the benefit of the global economy more generally.

"In addition, despite a notable rise in EME debt in recent years, which was accelerated by the pandemic, macroeconomic vulnerabilities are still generally lower than in the tumultuous years of the 1980s and 1990s: macroeconomic policies are more prudent, currencies are generally freer to respond to shocks, and financial sectors are more resilient.

Dillow notes that “if the Fed raises rates at a time when yields are rising because of increased optimism for the world economy, emerging markets will do well. But if on the other hand investors fear that higher short rates will weaken the economy and so bond yields fall, emerging markets will suffer badly.”

That leaves room for optimism these days, but he thinks its trumped by the slide in MSCI's emerging markets index (in US dollar terms) below its 10-month average. Although it’s not perfect, the indicator is good enough so that its current risk-off signal deserves attention, he concludes. Why?

“It protects us from the long and deep bear markets that really destroy our wealth. If your main objective is to avoid heavy losses you should stick with this rule even if doing so comes at the risk of missing out on gains. There is—as indeed there should be—a trade-off between capital preservation and profit.”