There’s no doubt that stocks have recovered handsomely from their January lows. And there has been precious little stress on the road to stock asset recovery since the start of 2016. Nevertheless, the fact that equities have toiled for the better part of two years…that’s not something that the media talk about in the papers or on TV.

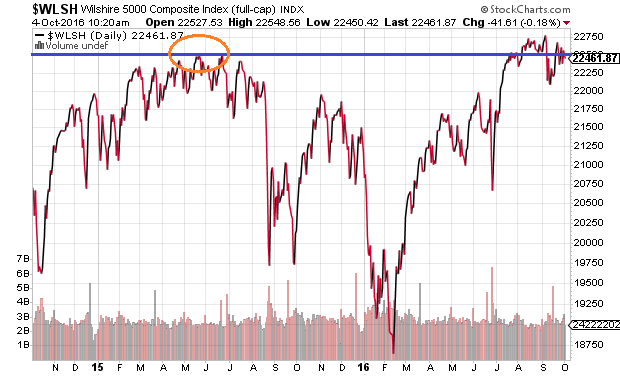

Let’s take a look at a chart of the Wilshire 5000 – an index that accounts for listings of all U.S. equities across all of the major exchanges (e.g., NYSE, NASDAQ, AMEX etc.). The Wilshire 5000 weighs larger companies more heavily. It also incorporates “FANG” stocks (i.e., Facebook (NASDAQ:FB), Amazon (NASDAQ:AMZN), Netflix (NASDAQ:NFLX), Google (NASDAQ:GOOGL)) that have largely carried market-cap weighted indices to new heights.

Indeed, the Wilshire 5000 has powered ahead by more than 8% over the last two years. That’s not too shabby. Yet the highs from May of 2015 still loom very large. Specifically, stocks may be sitting near a pinnacle, but they have not moved meaningfully forward in roughly 17 months.

There’s more. It would take little more than a garden variety 10% correction – the kind of pullback that we have seen twice in the last 17 months – to wipe out all of the unrealized growth in the last two years. With rate hike angst, the possibility of European bank contagion, U.S. election uncertainty and a sixth consecutive decline for corporate earnings on the table, does a 10% sell-off really seem far-fetched?

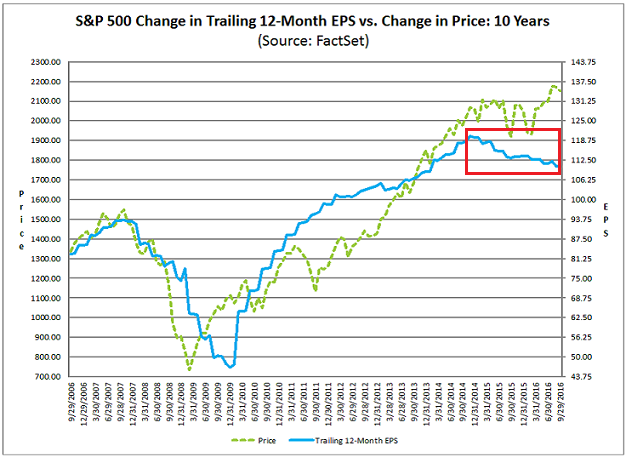

Indeed, the S&P 500 has been mighty resilient, remaining a stone’s throw from an all-time record. On the other hand, history has rarely been kind to stock assets when earnings per share (EPS) descend for as long as they already have.

There has been a straightforward explanation for the reason that stocks have held up as well as they have in spite of declining revenue and disappearing profits: central bank manipulation of rates around the globe. Yet the continuation, even the expansion, of these policies may be bumping into the law of diminishing returns.

Let us recall many of the primary reasons why central banks the world over (e.g., Federal Reserve, Bank of Japan, European Central Bank, Bank of England, etc.) have forced rates to obscenely low levels.

First, low rates theoretically stimulate debt-financed consumption, leading to significant gains in economic growth.

Second, low rates theoretically encourage long-term investment by businesses in their futures.

Third, lower rates theoretically devalue a currency, helping a country’s exports be more competitive as well as sparking inflation to make the repayment of debts easier.

Here’s the dilemma: Ultra-low interest rates are not necessarily helping with any of the above-mentioned items.

Start with economic growth. Debt-financed consumption initially sparked auto purchases, home buying, travel, eating out at restaurants and a number of other American “needs.”

On the flip side, when we add up what everyone has spent – a way that economists calculate economic growth via gross domestic product (GDP) – the U.S. recovery appears dismal. 1.4% and 0.8% GDP expansion in the first half of the year? 2.2% estimated for the third quarter? Before the current recovery that has barely averaged 2.2% since mid-2009, the average U.S. expansion clocked in at 3.3% annually.

Okay. So debt-financed consumption is not the panacea many had hoped for. Surely it has done a better job with encouraging long-term capital investment by businesses, right? If only that had been the case.

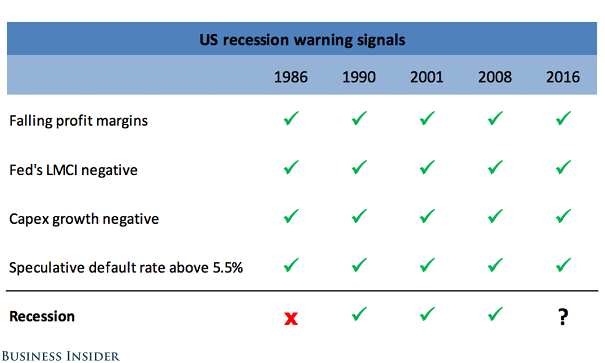

High quality businesses have doubled their total debt levels since the financial crisis, but very little of those borrowed dollars went toward R&D, marketing or new projects; very little went toward capital expenditures (CapEx). In fact, at present, investment in land, buildings, and equipment is actually contracting.

Okay. So economic growth has been less than inspirational. And corporate investment in respective long-term futures has been weak. Surely ultra-low rates have made American exports more competitive than ever. That might have been the case up until about two years ago.

Now that the Federal Reserve is only maintaining its balance sheet, as opposed to creating additional electronic dollar credits, PowerShares DB US Dollar Bullish (NYSE:UUP) trades near where it did at the start of quantitative easing (QE).

Is it any wonder, then, that corporate earnings have declined for six consecutive quarters? With the dollar’s elevated levels making exports more expensive? Is it any wonder that stocks have not been particularly impressive over the last two years, when currency devaluation has since shifted toward currency appreciation?

Granted, the Fed has barely moved its needle on rate hike ambitions; we still sit near the zero bound. Nevertheless, devaluation is difficult, if not impossible, when every other central bank in the world is pursuing a more aggressive rate lowering policy.

I contend that U.S. stocks will have trouble gaining significant traction when it is not easing as aggressively as other central banks; the Fed’s current level of accommodation may hinder businesses that generate up to half of revenue from overseas operations.

Bottom line? Ultra-low borrowing costs in the U.S. are not packing the kind of punch that they did between 2009 and mid-2014. With corporate capital expenditures contracting, with GDP slowing down on a calendar year basis, with the dollar settling in at elevated levels, ultra-low borrowing costs are not likely to boost stocks in the way that they have in previous years.

Disclosure: Gary Gordon, MS, CFP is the president of Pacific Park Financial, Inc., a Registered Investment Adviser with the SEC. Gary Gordon, Pacific Park Financial, Inc, and/or its clients June hold positions in the ETFs, mutual funds, and/or any investment asset mentioned above. The commentary does not constitute individualized investment advice. The opinions offered herein are not personalized recommendations to buy, sell or hold securities. At times, issuers of exchange-traded products compensate Pacific Park Financial, Inc. or its subsidiaries for advertising at the ETF Expert web site. ETF Expert content is created independently of any advertising relationships.