Summary: The cumulative advance-decline (A-D) line for both the NYSE and SPX made a new all-time high (ATH) last week. That's good news for stocks, as they most often move higher in the following weeks/months, also to new highs.

This is probably the best way to use the A-D line in equity research. Other common uses of A-D line are fraught with issues.

For example, while it's true that the A-D line has often weakened before stocks have encountered a major decline, you'll need hindsight to make use of this information. For every time a weakening A-D line has signaled a major fall it has signaled nothing special at least twice as often. "Negative divergences" happen all the time. In real-time, it is impossible to know when a divergence is worth paying attention to.

* * *

Last week, the cumulative advance-decline (A-D) line for both the NYSE and SPX made a new all-time high (ATH). The A-D line sums the net number of stocks moving up on the day added to yesterday's total. The idea is that when the A-D line is rising, more stocks are moving higher and breadth is considered healthy. In other words, it's a bullish sign for stocks.

Let's start with the good news.

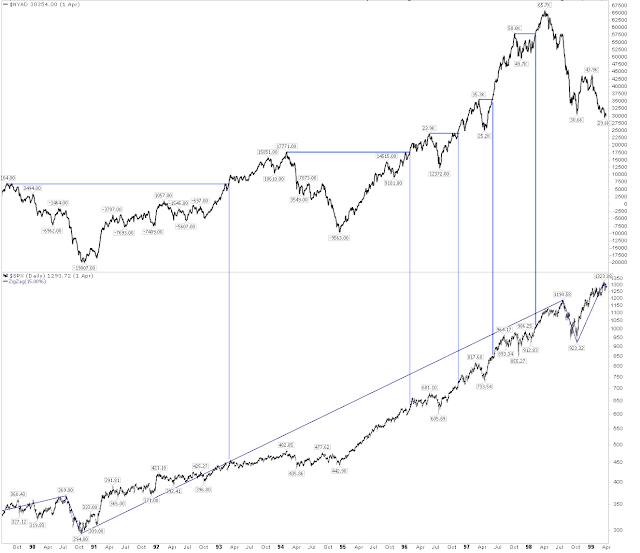

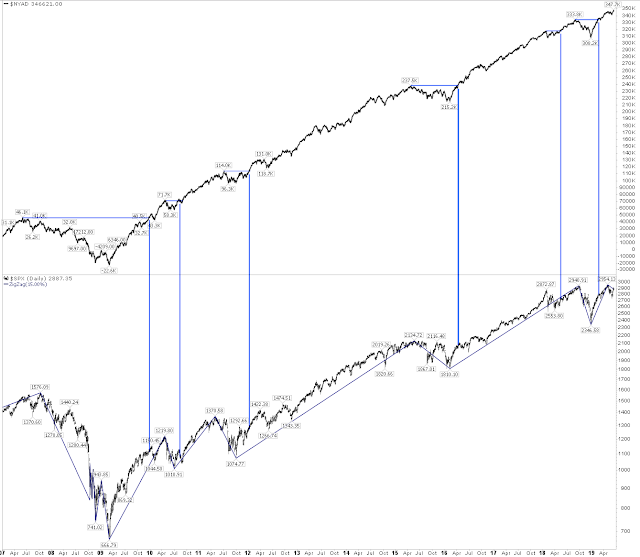

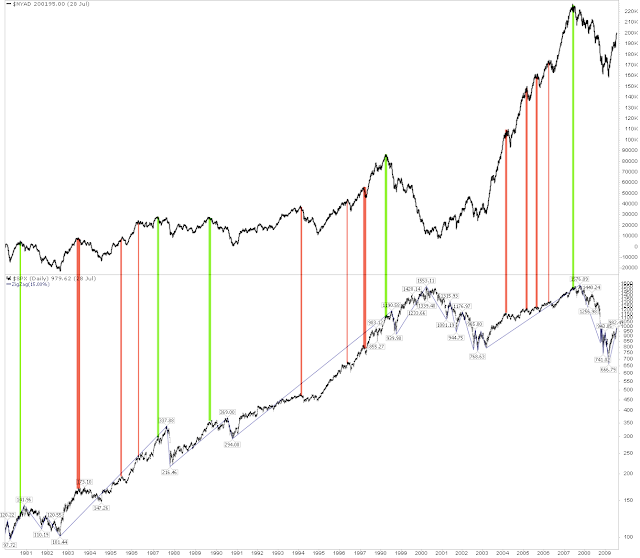

The charts below show every "breakout" in the NYSE A-D line to a new high (top panel) and what happened next to SPX (lower panel) in the past 30 years. What we find is that in every case, SPX has moved higher in the weeks/months ahead.

The not so good news is that the gains haven't always been right away. In the chart above, note how SPX went nowhere for several months in 2016. That was also the case in 1993 and 1996, for example.

But, all things considered, the breakout to a new high in the A-D line while SPX is still below it's own ATH looks bullish. With SPX not even 2% from its April ATH, we should expect a new ATH in the weeks/months ahead.

Those results are confirmed by Sentimentrader: since 1950, a new high in the A-D line when SPX was less than 10% from a 52-week high has been followed by a new ATH within 3 months in 81% of instances. The median gain 3 months later was about 4%.

This is probably the best way to use the A-D line in equity research. Other common uses of A-D line are fraught with issues.

The most popular way to use the A-D line is to identify major stock market tops (defined as a fall greater than 15%). It's true that the A-D line has generally (but not always) peaked and started to decline before stocks have encountered a major decline, but you'll need hindsight to make use of this information.

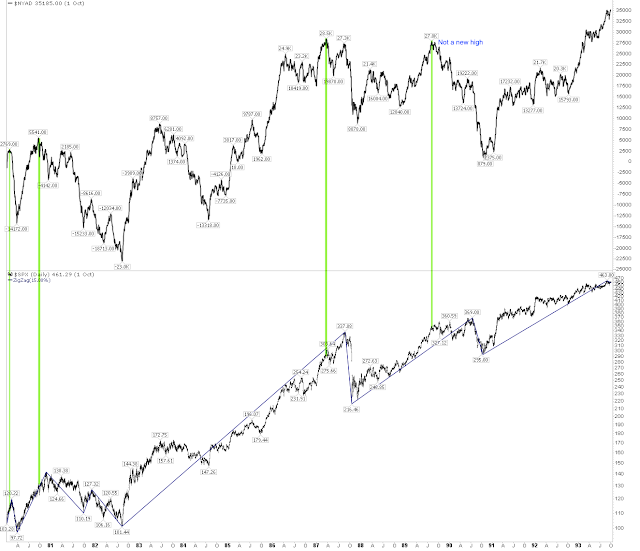

The charts below compare the NYSE A-D line (top panel) to SPX (bottom panel) since 1980. The green lines indicate periods before a larger than 15% fall in SPX that were preceded by new high and then decline in the A-D line. In the first chart, between 1980 and 1993, there were 4 major falls in SPX and the A-D line weakened from a peak before each one.

Likewise, between 1997 and 2008, the major declines, including both the 2000-02 and 2007-09 bear markets, were preceded by the A-D line weakening from a peak.

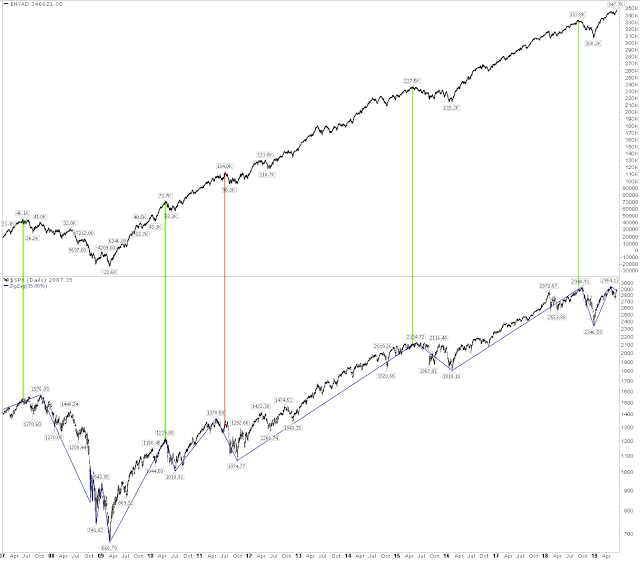

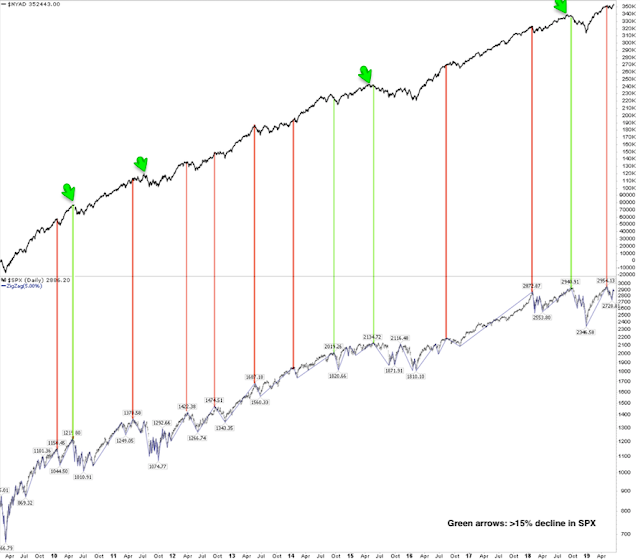

There have been 4 major declines in stocks since 2009. The A-D peaked before 3 of these (although the time lag was very short). The 2011 decline was an exception in that the A-D line peaked after SPX had already started to fall (red line).

So, out of 11 major declines in stocks since 1980, the A-D line has started to fall ahead of 10 of them. That looks pretty good. But can you use this in real-time?

Unfortunately, the answer is no. For every time the A-D line has signaled a major fall (green line) it has signaled nothing special at least twice as often (red lines). "Negative divergences" happen all the time. In real-time, it is impossible to know when a divergence is worth paying attention to.

Another problem in using the A-D line is this: the vast majority of declines in stocks of at least 5% are virtually coincident with a high in the A-D line. Just as stocks are peaking, so is the A-D line. In real time, this is often viewed as bullish, that "breadth is confirming price." It's not bullish.

The chart below shows just the last 10 years, with red lines indicating new highs in the A-D line coincident with an uptrend high in SPX. This is the majority of cases before a fall of 5% or more. The green lines show when the A-D line peaked and started to decline before stocks, which is the minority outcome.

So if you are expecting the A-D line to signal weakness in stocks ahead of a decline in stocks of 5-10%, you're in for a bad surprise.

Why is the utility of the A-D line so limited?

We have previously described the problems in using breadth for identifying market inflection points. In short, the conventional wisdom that new highs in the stock indices should be confirmed by an expansion in breadth is empirically false. Indices have typically been driven higher based on a small number of stocks contributing disproportionately large gains. Over the past 20 years, just 4% of stocks have accounted for an astounding 68% of the gains in the SPX (read further here).

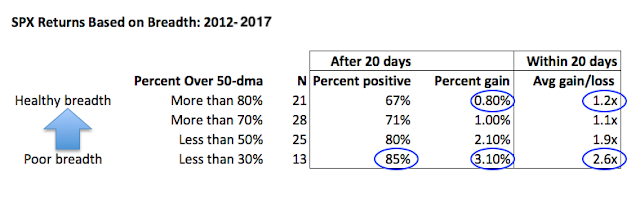

Moreover, stock market returns have typically been best when breadth is worst. From 2012 to 2017, the SPX has gained more than 3 times as much over the following month when breadth was weak compared to when breadth was "healthy." Risk/reward was more than twice as favorable when breadth has been weak as when it was healthy.

The A-D line has specific conceptual issues. Again, the A-D line sums the net number of stocks moving up on the day added to yesterday's total. But if a lot of small stocks move up by one penny on low volume but slightly fewer large companies move down a dollar on high volume, the cumulative advance-decline line still moves higher. Or, if a large number of defensive stocks move up while "risk-on" cyclical stocks move down, the cumulative advance-decline line moves higher. Neither of these is a sign of market health.

In summary, the new ATH in the A-D line for both the NYSE and SPX last week is good news for stocks, as they most often move higher in the following weeks/months. This is probably the best way to use the A-D line in equity research.