Stock markets initially plummeted on the notion that the Federal Reserve would print less money, buy less government debt and stand by as interest rates soared into the stratosphere. Very quickly, however, Fed officials extinguished fears of skyrocketing borrowing costs by simultaneously announcing that its policy of zero-percent overnight lending would continue “well beyond” the point at which unemployment reached 6.5%. In other words, the U.S. central bank “taketh” away a bit of its electronic dollar creation, yet “giveth” enormous assurances that it remains dedicated to suppressing interest rates — by one method or another — well into the future.

In Chairman Bernanke’s news conference, he once again emphasized that tapering currency creation does not constitute tightening. In the past, I have found this idea comical if not downright ludicrous. On the other hand, if one sets out on a course of slowly exiting from a controversial easing program that involves generating more of a currency that had not previously existed, but also guarantees that other easy money policies will remain intact for much longer than anyone would have surmised, the net result constitutes an equivalent level of accommodation. Indeed, the outgoing chairman stated that “The Federal Reserve means to keep the level of stimulus more or less the same.”

Equity enthusiasts obviously agreed. The Dow surged 292 points and the S&P 500 closed at a record high on Wednesday (12/18). Equally compelling, many of the premier performers in the Fed-fueled rally came from rate-sensitive sectors like iShares DJ Home Construction (ITB); the exchange-traded fund pole vaulted 3.7% in the single session.

Perhaps ironically, the modest tapering from $85 billion per month to $75 billion per month might even be deemed looser monetary policy. How? The Fed now promises to give greater weight to a wider variety of data in its assessment of employment well-being — things like labor force participation and wage growth. Since these indicators are a long way from looking as rosy as the Bureau of Labor Statistics “7% unemployment” data point, one should recognize that the Fed is determined to keep the cost of borrowing in check for many years to come.

Not sure about the analysis? Consider the possibility that the Fed actually tapers another $10 billion at every committee meeting throughout 2014. The quantitative easing (”QE3″) that would still occur would be as large as the previous round of easing (”QE2″); in fact, another $600 billion would still be added to the Fed’s balance sheet, bringing the amount of new dollars into existence closer to $5 trillion. Meanwhile, any hiccups in gross domestic product, real estate or joblessness could result in Fed meetings where they skip a $10 billion reduction and/or announce thresholds that give zero-interest-rate-policy an aura of total permanence.

Is anyone really shocked that trillions of new greenbacks alongside exceptionally low interest rates enticed borrowing activity? Are we surprised that consumers, businesses and investors have been clamoring to gain access? Unfortunately, few seem concerned that 2013 debt levels and other debt measures are now greater than they were in 2007; we’ve worked our way back into the same dangerous thought process that leverage can only be positive. In truth, I am not sure why so many economic experts are forecasting an endless economic expansion in the wake of developed-world government debt that is twice as large as it was five years earlier.

Theoretically, the next stage of expansion would come when banks begin lending significantly more of the money that they borrowed for a song. They have been relatively stingy up until now, though many folks are optimistic that — alongside repaired balance sheets — banks will loosen up their own reins. I’m not so sure. Perhaps if the White House and Congress pressure the banks to lend to less qualified applicants, bank profits will grow and consumers will be giddy with the extra dough. Of course, these are the same types of “community reinvestment” issues that occurred leading up to the financial collapse circa 2007-2009.

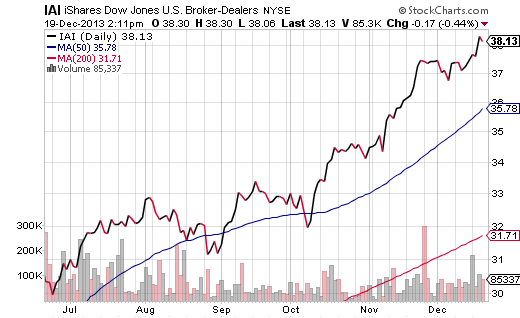

As I wrote in a a previous column, I would be more comfortable with regional banks than the big boys. Primarily, they understand that they are not too big too fail, so they tend to be smarter about the quality of the loans that they add to their books. Investors might be wiser to pursue SPDR S&P Regional Banking (KRE) over SPDR S&P Bank (KBE) or SPDR Sector Financials (XLF). Moreover, with or without a 2014 correction, I expect brokerages to reap the rewards of stock and stock ETF inflows. iShares U.S. Broker-Dealers (IAI) could be a venerable pick-up on a pull-back to its 50-day trendline.

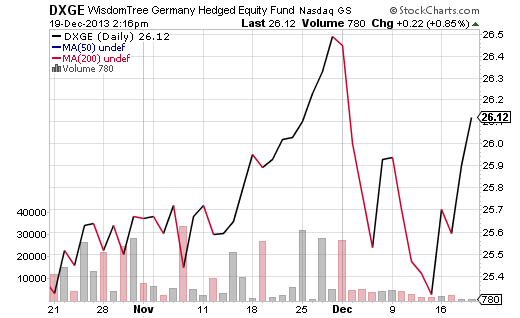

The Fed’s determination to keep rates relatively subdued, even as it is curbing dollar creation, may be more beneficial to dollar-hedged foreign equity funds. In particular, funds like WisdomTree Hedged Japan Equity (DXJ) and WisdomTree Hedged Germany Equity (DXGE) are attractive from a valuation basis as well as a currency basis; expect the yen and the euro to depreciate against the dollar.