Friday, January 26, stocks hit their last record highs. Buoyed by supposedly strong earnings along with near euphoria about tax reform anecdotes, all three major US indices were sitting at their respective tops after another big week. Everything was apparently going in the right direction:

All the three key U.S. indexes closed at record levels on Friday following better-than-expected earnings from Intel (NASDAQ:INTC), AbbVie Inc (NYSE:ABBV) and Honeywell International Inc (NYSE:HON). Additionally, continued economic growth and optimism over a weaker dollar had a positive impact on investor sentiment. The S&P 500 has finished at a record level for 14 trading days so far this month, its best such feat in a month since June 1955. The index also posted its best one-day rise since March 1, 2017.

Over the next few weeks, however, stocks across the world were slammed by a wave of liquidations. Confused and disoriented, mainstream commentary began to zero in on first VIX (and its inverse XIV) and then inflation hysteria. According to the latter, the economy globally was about to become so good it was bad. Central banks, they said, will have to act faster than expected to restrain the boom.

Almost two months later, however, VIX is long forgotten and inflation is heading that way, too. Yet, a lot more than stock market indices remain on the downside of January 26.

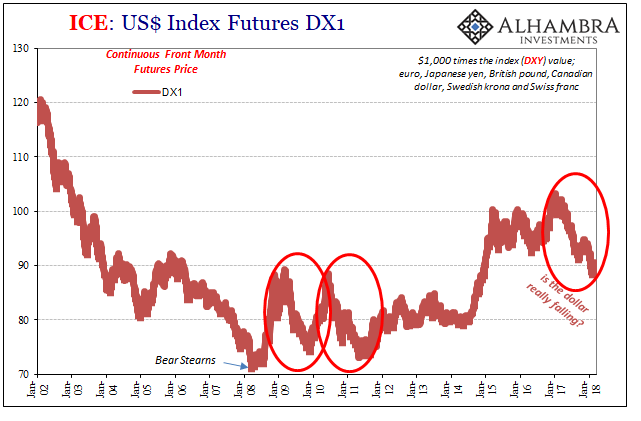

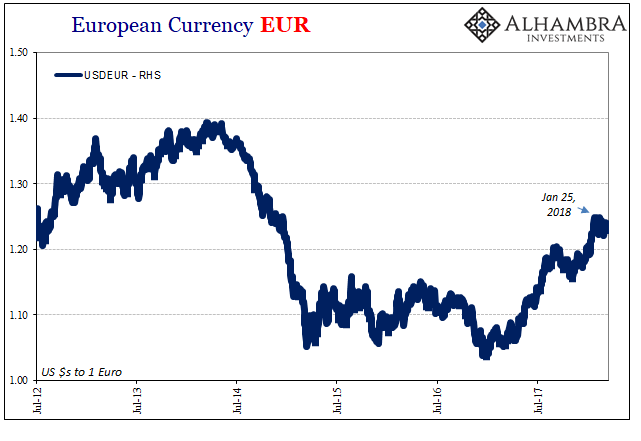

First on that list is the euro. Nothing was more emblematic of last year’s weak dollar than Europe’s currency. First, it ran contrary to the established conventional wisdom where the Fed raising rates should be dollar rather than euro positive. In other words, it was global “reflation” in the same sort of way as 2011.

The euro hasn’t gone any farther than it did at the end of January. The exchange rate hasn’t tumbled, either, but its sideways action proposes a lot of other similar action, from oil to UST nominal yields. The dollar is in the middle of everything, just not in that conventional sense.

The exchange value is in many ways pretty simple economics (small “e”). It moves on supply and demand, where during 2014-16 the “rising dollar” was both a surge in short-term demand for offshore “dollar” funding but also a parallel reluctance on the part of global banks to supply it. That’s why it moved so far and so fast during that time and was so destructive as it jumped.

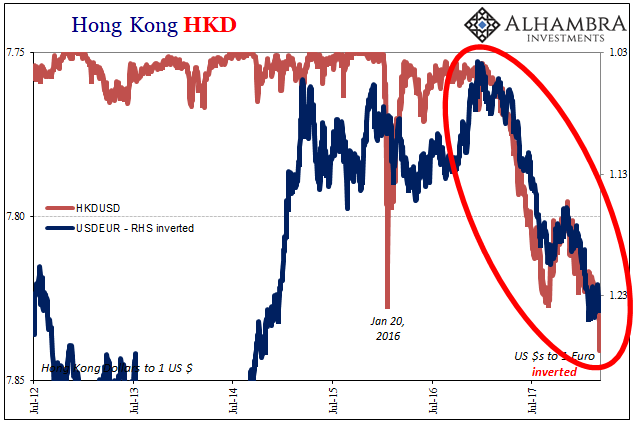

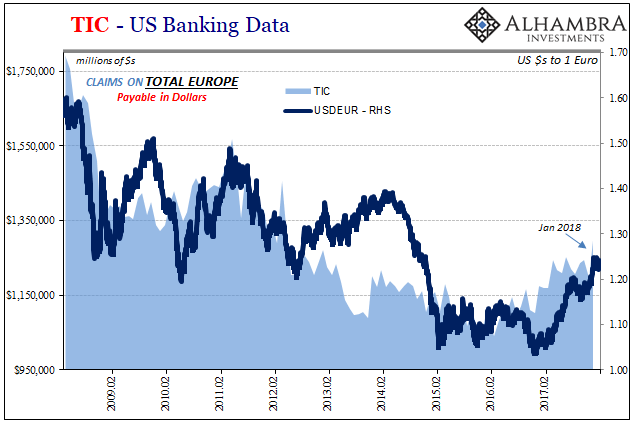

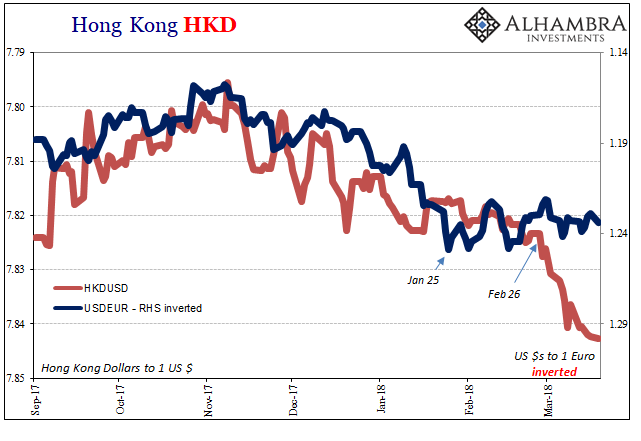

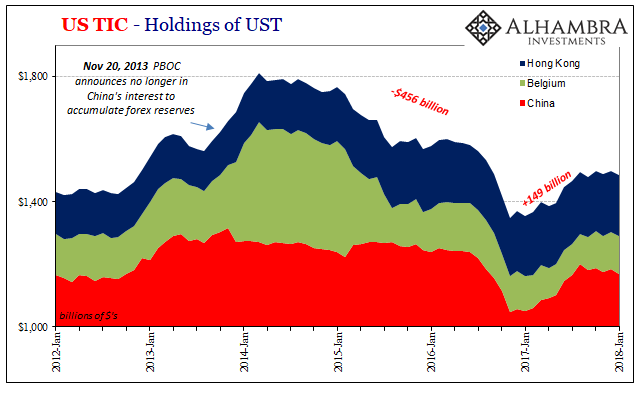

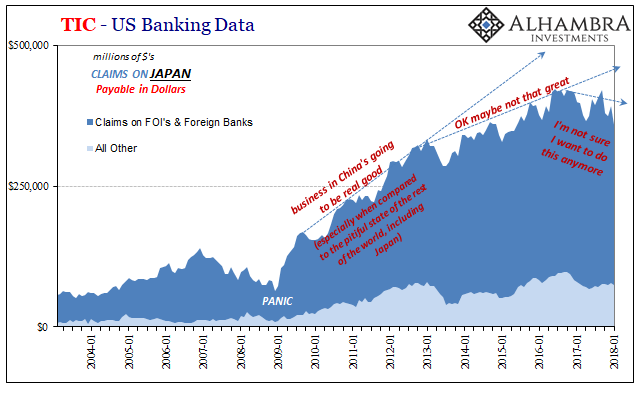

In 2017, by contrast, supply seemed at the very least somewhat better consistent with the textbook monetary case for reflation. The big change in CNY along with its inverse HKD suggested there were “dollars” being supplied to China via Hong Kong from somewhere else. That somewhere appeared to be European banks coming back into the dollar business for the first time in about seven years.

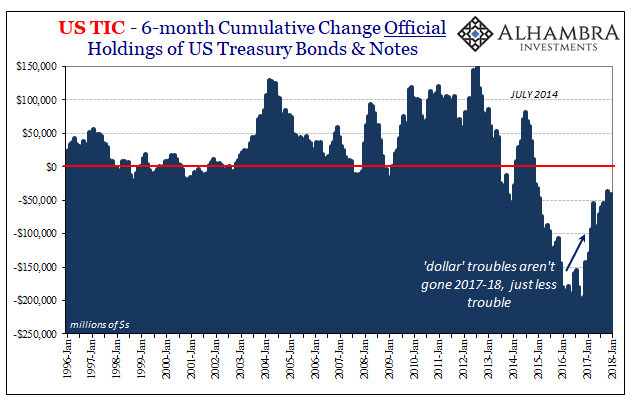

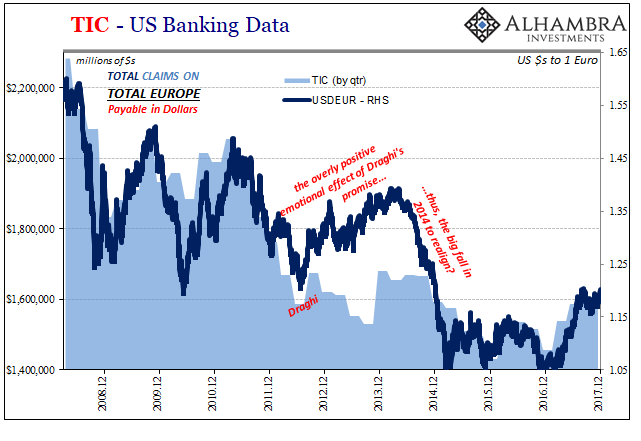

But it wasn’t a full-throated resurrection of the pre-crisis eurodollar, along with its European center of gravity. The reflation trend, as exhibited in both EUR as well as data proxies like TIC’s cross-border US banking statistics, suggested a great deal of caution in this shift toward optimism. As I wrote on January 26 (completely coincidental timing):

The response in Europe was somewhat favorable to the proposition, to pick up some of the slack in “dollars”, but only some. And it’s causing HKD distortions along the way (now a triumvirate of CNY/HKD/EUR, with HKD on the losing end). Furthermore, given when all this started, I have to believe that underpinning Europe’s apparent generosity are first a whole bunch of trading premiums we have no idea about (is someone, PBOC, subsidizing somewhere along the way?), but more so some further risk/return assumptions that may not last all that long. [emphasis added]

If European banks are behind China’s Hong Kong bypass to a substantial degree, that’s why HKD matters. As it falls it proposes risk even in what was supposed to be stable. Hong Kong’s banks were the perfect stand-in for Chinese counterparties when the latter had become avoidable due to perceptions about China and Chinese funding necessities (the “rising dollar”). HKD falling apart places HK banks into the same kind of risk regime.

Going back to January, then, US TIC data records a large increase in European dollar activities (showing up as US bank claims on European banks payable in dollars). That corresponds to the last run-up in the euro, or the last big weak dollar move that to this point ended back on January 26.

Since then, as noted above, USD/EUR has stopped rising as has “reflation” overall, proposing diminishing or at least more expensive dollar supply via Europe and into Asia. That may be why HKD has plummeted starting around early February when the global stock market liquidation really picked up. Such obvious levels of funding risk (on both sides) might have caused some considerable reluctance on the part of European banks to supply marginal funding in eurodollar markets to not just Hong Kong counterparties but also in broad(er) fashion.

Having become “hooked” on obtaining dollars for China, HK’s dubious entry into the global “dollar short”, any problem in funding those rollover liabilities shows up as falling local currency. The lack of rise in EUR at the same time suggests who it is that isn’t meeting the demand any longer.

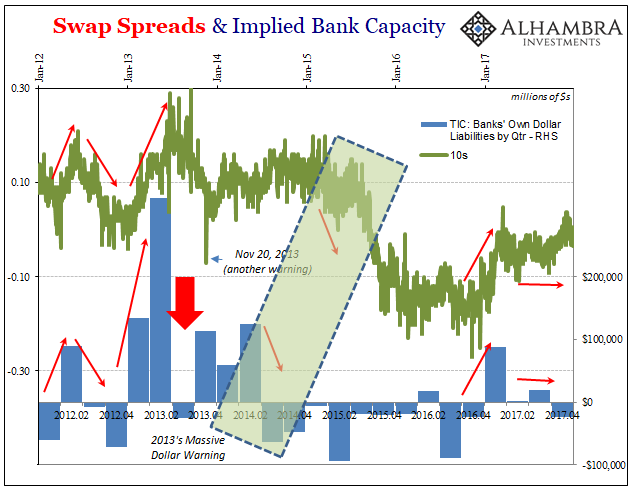

Thus opens a whole range of possibilities for perhaps a more complete systemic inflection in January and February (and likely into March). We knew at the end of 2017 that “dollar” markets were already far less than ideal, repo and the global basis, to put it mildly. What we may be witnessing January 2018 forward are the consequences.

These things are processes and so they don’t always happen on a one-to-one relationship. The big change in bank balance sheet capacity in the middle of 2014, for example (shown above), wasn’t fully processed until later in the beginning of 2015 as a more complete downside inflection.

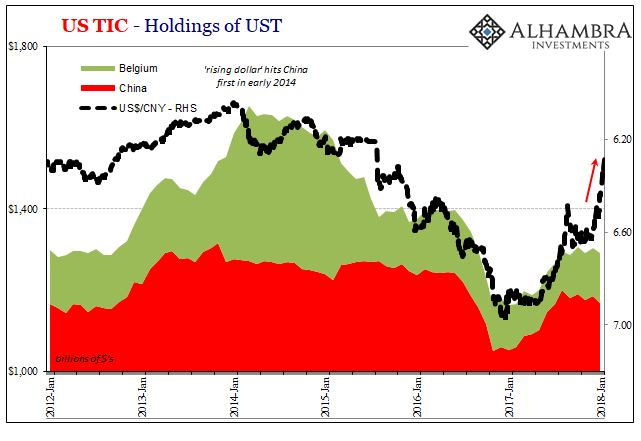

The latest update from TIC, for the month of January 2018, is full of such things. The most puzzling is the sudden divergence between CNY and the holdings of UST’s in Chinese hands. Throughout the “rising dollar” period as well as the following “reflation” out of it, the level of UST’s reported by China and Belgium combined was a near perfect match. Not so in January 2018.

Including Hong Kong along with those two countries, the combined balance was lower as it has been going back to September last year. Detaching CNY from that basis proposes quite a few possible problems and imbalances that might have global consequences.

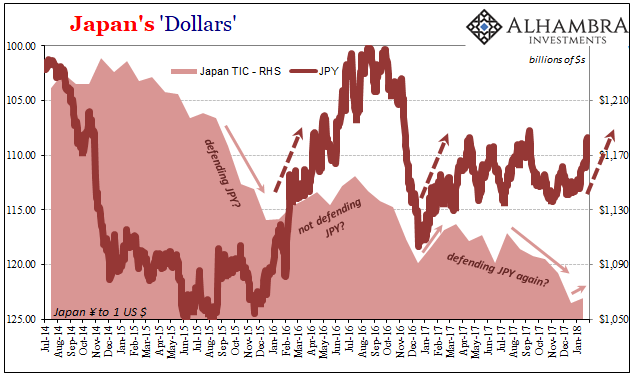

Not only that, as we noted for December’s TIC update, JPY was in danger of rising as a result of several related factors (related in the sense of being ahead of Europe in being removed from the dollar business). Unsurprisingly, Japan’s reported holdings of UST’s rose in January, suggesting again this difference in overall “dollar” orientation.

A week before the EUR reached its zenith, JPY was already moving sharply higher unsupported (as we know now) by official/unofficial actions in relation to Japan’s forex reserves and their availability (including UST/JGB swaps for US$ repo). JPY would reach almost 105 by early March, the highest it had been going back to late 2016.

That’s a lot of moving parts and missing pieces. In broader, more general terms, what it’s all getting at is a distinct change in January involving all the usual suspects – China, Japan, Hong Kong, and Europe. Where did inflation hysteria disappear to? The short answer cannot ever have been VIX. Instead, it’s suggested right in those same places, starting with European banks looking at Hong Kong and possibly regretting (and then rethinking) their primary role in 2017’s “reflation.”

The world really wants to love and embrace the weak dollar because that’s where all the bubbly fun comes in. Since Bear Stearns, however, the weak dollar is just those times when the system grows calm enough that worries and imbalances fall back into the shadows. They don’t disappear, but they recede far enough beneath the surface that it’s very tempting to think they do.