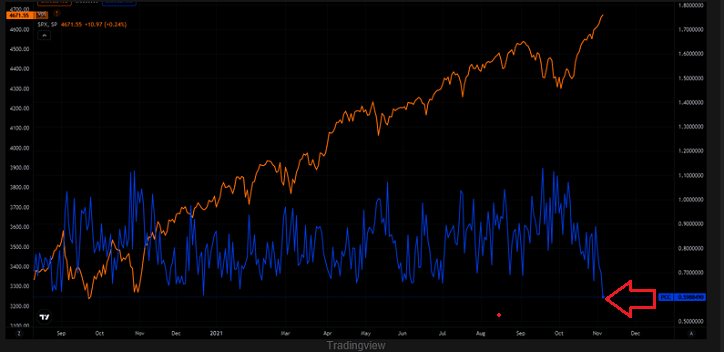

Stocks recently hit record highs here in November. Similarly, the volume associated with protecting one’s stock portfolio with “put options” has fallen to a new low.

What do these trends suggest? They imply that investors believe that things are different than when stocks collapsed in 2000; things are different than when stocks crashed in 2008.

In particular, the investment community is comfortable with the protection supplied by central banks like the Federal Reserve. Who needs to actively guard against stock loss when the almighty “Fed put” can prop up asset prices?

The “Fed put” references the notion that the Federal Reserve is not only capable of bailing out assets (e.g., stocks, bonds, real estate, etc.), but that it would not hesitate to do so if a corrective period turns bearish. To avoid 30%, 40%, or 50% losses, the Fed would deploy electronic money printing, asset purchasing, and rate manipulation to maintain a floor underneath asset prices.

However, there are problems with the “Fed put.” For example, it assumes that the central bank will let the cost of living rise dramatically and ignore its mandate to maintain the stability of people’s purchasing power.

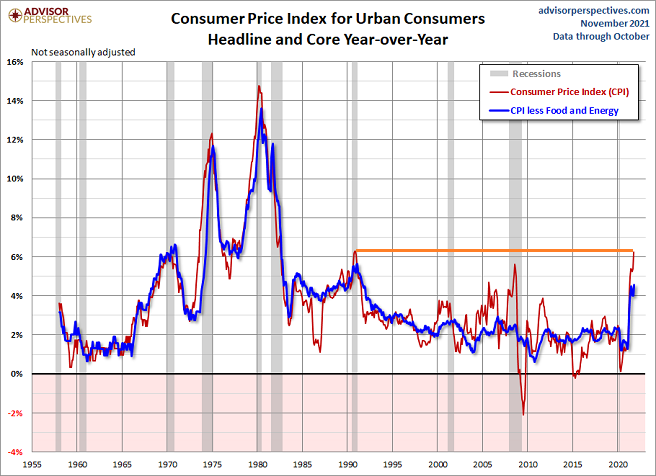

Ignoring inflation and calling it “transitory” has worked for Jerome Powell so far. Yet data points showing the worst inflation in 30 years may make it more difficult for the Fed chairman.

Granted, the Fed is more likely to let inflation run hot for a bit, as opposed to spooking participants with rapid-fire rate hikes. Yet the markets may ultimately chart their own path.

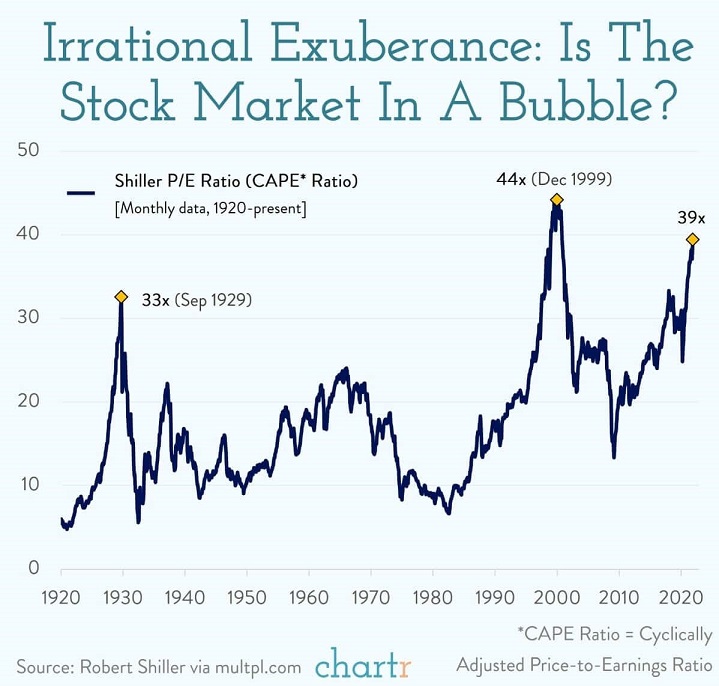

Consider the reality of bubbly valuations. Frothy P/Es coupled with inflationary data as well as political pressure may keep the Fed “honest.” Said differently, if stocks sink, it may not be so easy for the Fed to ride to the rescue with trillions in market liquidity.

There’s another reality. Even if the Fed rides to the rescue in a sell-off with another round of electronic money printing and asset purchasing, financial system participants may prefer the perceived safety of negative-yielding cash to stock market volatility and hyper-valuation.

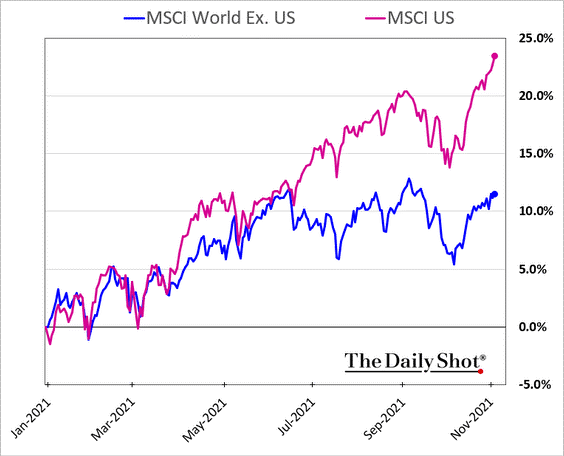

Still another possibility? The decade-long dominance of U.S. stocks disappears, disappointing mega-cap growth zealots.

For those that grow skittish about U.S. stock pricing, and who may grow skittish about leaving money in the safety of cash, the demand for foreign shares could easily swell.

The infatuation with U.S. innovation and mega-cap domestic securities has persisted throughout the year. In fact, it has persisted for the better part of the last decade.

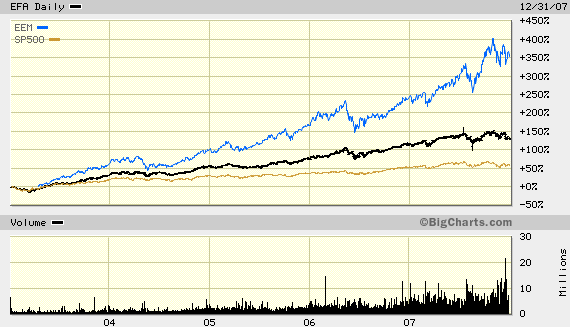

On the flip side, it is worth recollecting what transpired after the 2000-2002 tech wreck. Investors began shunning U.S. equities for the relative attractiveness of foreign stocks. If you were not interested in Europe, Brazil, China, and India, then you were “missing out!”

In sum, U.S. stocks may not be a can’t-lose proposition. Not if foreign stocks present a more sustainable risk-reward going forward. And not if perceived safer havens like cash or precious metals displace U.S. stock invincibility.