As outlined in our previous articles in November and December, we anticipate uranium prices to improve significantly in 2014 for a number of reasons. Today, the fundamentals for uranium and nuclear power generation are stronger than ever. More reactors are under construction, planned and proposed than before the Fukushima incident.

For uranium prices to appreciate in the foreseeable future, one must look not only at the reactors under construction worldwide, but the ones coming online soon. China has 28 reactors under construction, yet 5 are ready to be connected to the grid this year. Japan has submitted applications for 17 reactors to be restarted, whereas analysts are expecting at least 6-8 reactors to be granted permission for restart in 2014. Both China and Japan are set to add vast amounts of demand back into the uranium market.

The US is more dependent on foreign uranium supply than it is on foreign oil, as yearly consumption exceeds 23,000 tonnes of uranium, whereas domestic production accounts for less than 2,300 tonnes. In 1993, the US and Russia signed the ‘Megatons to Megawatts Program’, whereby USA bought 500 tonnes of Russian surplus high-enriched uranium (HEU) from nuclear disarmament and military stockpiles over 20 years, this having ended last year.

“The Megatons to Megawatts program made a substantial contribution both to the elimination of nuclear weapons material in Russia, and to nuclear energy generation in the United States. Nearly every commercial nuclear reactor in the US received nuclear fuel under the program.”

(Ernest Moniz, US Energy Secretary, in 2013)

According to the latest January 2014 update of the World Nuclear Association:

- These 500 tonnes of HEU, delivered in form of downblended LEU (low-enriched uranium) inside more than 200 vessels crossing the Atlantic, were supplying around 10% of all US electricity over the past 15 years representing about 12% of world uranium demand in recent years.

- These 500 tonnes of HEU had the equivalent of around 150,000 tonnes of natural uranium (177,000 tonnes U3O8, or 2.5 times annual world demand), of which 112,000 tonnes sold on the market.

- This is equivalent to an average of 8,850 tonnes U3O8 per year from global mines over the past 20 years.

Already in 2011, USA and Russia signed a new contract for future supply, however the LEU will, from now on, come from Russia’s commercial enrichment activities rather than the downblending of weapons material. As per the new agreement, supplies to the USA are to be increased until 2015 to half the level supplied under the prior HEU program (option exists to supply up to the same level) and are expected to continue until 2022. However, according to the new contract, the feedstock for the LEU must come from sources other than Russian domestic mine supply. Hence, the replacement agreement is merely an enrichment services agreement and nothing more. The US is now called upon to source new uranium, deliver it to Russia for Russia to enrich, and then buy the resulting LEU.

In essence, the replacement agreement does not help the US meet their need for sourcing supply in any way. It gets worse.

While consuming some 23,000 tonnes U3O8 per year and domestically producing only 2,300 tonnes, the US is now on the hook for at least 20,700 tonnes every year, and it is anyone’s guess where that uranium will come from. The number is likely higher as the majority of US mine production is owned by the Russian government, and the Russians are within their rights to export it all back to Russia if they so desire.

The supply side looks favorable for higher uranium prices as the extremely low prices have the side-effect that numerous mine development projects have been delayed, put on hold or outright canceled, tightening supply significantly for many years.

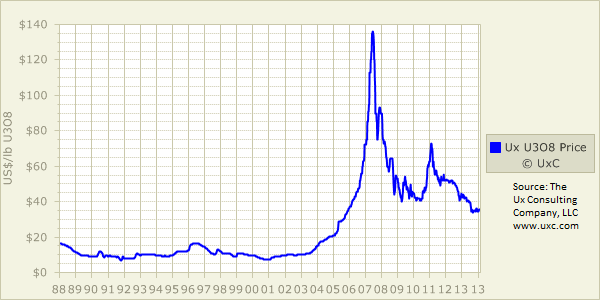

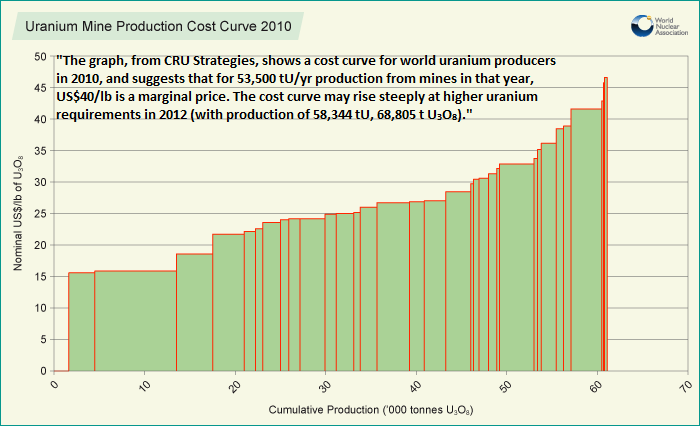

The uranium market is facing a dramatic supply risk due to low market prices. The average marginal production costs for global mine supply stands at around $40/pound, yet spot prices trade at $35/pound today. JPMorgan and others warned that the market must recover to $75-$80/pound to incentivize the development of new uranium projects.

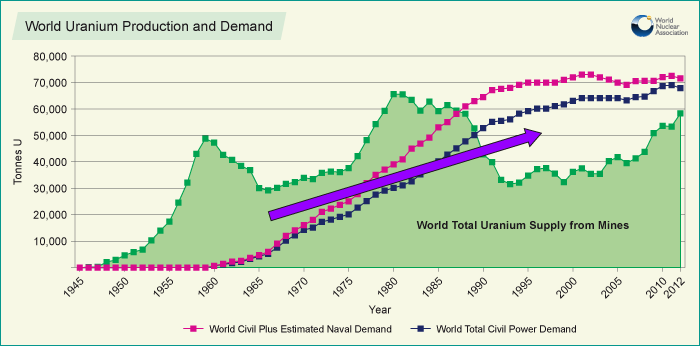

While there was more mine supply than demand between 1950-1990, demand is outpacing mine supply since then:

Why are uranium prices so low and why is a strong rebound on the horizon?

“Some 20% of the world’s major large reactors are lost to production. All 55 Japanese reactors have been shut down, 6 permanently.That caused a huge inventory of unused fuel and contractually committed fuel for long-term supply with nowhere to go. They can repackage that, and some has been repackaged and used elsewhere. But excess inventory caused by Japan is the number one reason for low uranium prices. Related to that is the absolute pause that happened in the world after March 2011. There was a gigantic pause button pushed in China, in India, and to some limited degree in Russia. That meant a lot of the long-term supply contracts were leading to excess inventories in other countries. My experience in Japan suggests there’s a gigantic tug of war happening. At one end is the Abe government and its ministries, which are determined to try to bring the reactors back. Why? Because of the sheer cost of replacement fuels, of having to build LNG plants, coal-fired power plants and to some limited degree renewable power plants. They import 90% or 95% of the fossil fuels that they burn.All of that means they want to bring back viable power sites.” (Thomas Drolet in a recent interview “The Fukushima Effect”)

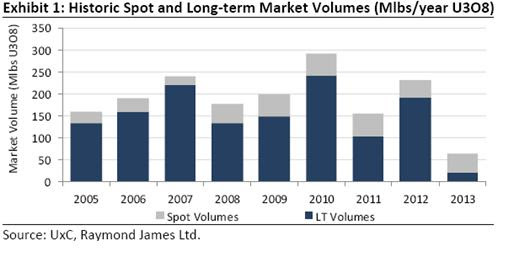

Besides the large amounts of uranium inventories, another reason why uranium prices are so low is due to unprecedented low demand by nuclear power generation utilities. Normally, the lion’s share of physical uranium is transacted via long-term contracts. For nuclear utilities, the costs of uranium is somewhat negligible as it only makes up around 10% of total costs, hence supply security is much more important to them than the question if uranium costs $35 or $70 per pound.

Energy companies normally buy ahead their uranium requirements for 3-5 years; as the below chart shows this was the case for many years, stunningly however this was not the case in 2013. Due to Fukushima and the shutdown of all Japanese reactors, suddenly there was too much uranium available in the market. It seemed as there were no dangers of supply security for which reason more uranium was traded via the spot price than with long-term contracts:

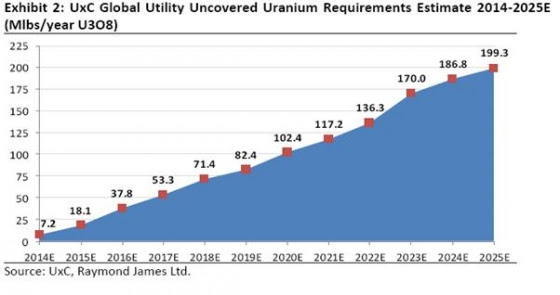

As above chart indicates, nuclear utilities have neglected long-term procurement in 2013 as having acted sparsely only in the spot-market. However, utilities are expected to be short of 7.2 million pounds in 2014 already, whereas uncovered uranium requirements are estimated to escalate in the years to follow:

The behaviour of utilities in 2013 secures low prices only in the short-term as their requirements, which are not covered by long-term contracts, are short 7.2 million pounds this year already. As new reactors coming online worldwide, this number is set to increase substantially over the next years. The current supply security is illusive, because the current supply only looks copious until the first utilities change back to the historic customary trading strategy of long-term contracts. Those utilities waiting too long will realize:

The capacities of producing mines are not sufficient to compensate future demand at current prices.

In October 2013, Areva warned its clients not to bet on low prices for much longer but to secure their long-term procurement until latest by 2015 – in order not being forced to compete with utilities from China, Russia, India or South-Korea. Until today, this warning remains unheard, and despite the World Nuclear Association forecasting a demand growth of 48% until 2023.

The reason for utilities behaving like this is that there exist forecasts calculating a supply surplus until 2016, whereupon a deficit is expected. However, these forecasts are dubious and not reliable anymore. Since December 2013, 4 uranium mines with an annual output of 22.4 million pounds (around 15% of global mine output estimated for 2014) have temporarily suspended their operations: Ranger Mine (Australia), Rössing (Namibia), Cominak and Somair (Nigeria). Ranger and Rössing, both operated by Rio Tinto, are fighting with leaking toxic sludge, whereas Areva has not yet been successful in negotiating a new royalty scheme with the Nigerien Government. It is still unclear when Areva’s mines will open up again. In particular, Areva is not capable of profitably operating its Nigerien mines at current low uranium prices if the government indeed will increase royalties from 5.5% to 12%.

“Although the value of the uranium production from Nigerien mines is not terribly significant in dollar terms – approximately $500 million per year in today’s prices – what is significant is that France derives 78% of its electricity from nuclear reactors, and approximately 1/3 of the fuel for those reactors comes from Niger. Areva operates the mines, and is the third largest uranium mining company in the world in terms of production, mining 17% of the world’s uranium supply last year. 45% of that production came from Niger. It isn’t too difficult to guess how badly things could turn out for France if their Nigerien supply of uranium was abruptly cut off – 26% of France’s power-generating capability would be shut down.” (Canon Bryan in “Bombed Areva suffers from ‘This Is Africa’ Syndrome”, May 2013).

In May 2013, 23 people were killed and 13 Areva employees were injured when rebels bombed an uranium mine in Niger. Africa is one of the toughest places for mining commodities. A safe and reliable mining jurisdiction is key for long-term security of uranium supply, yet most deposits occur in somewhat problematic systems of justice, including Kazakhstan, Russia, and Australia. Canada is the best place in the world to do uranium exploration and mining.

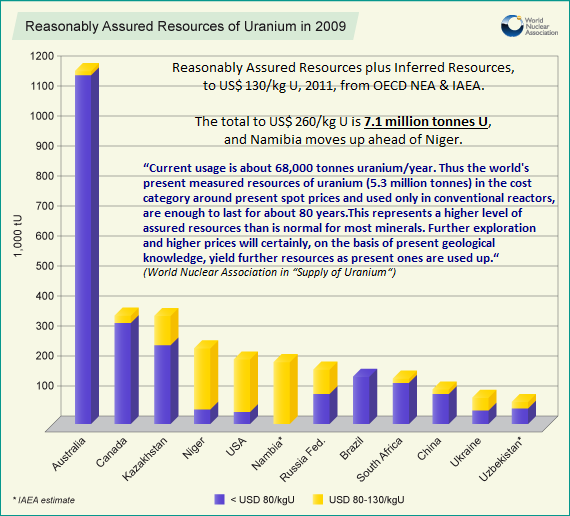

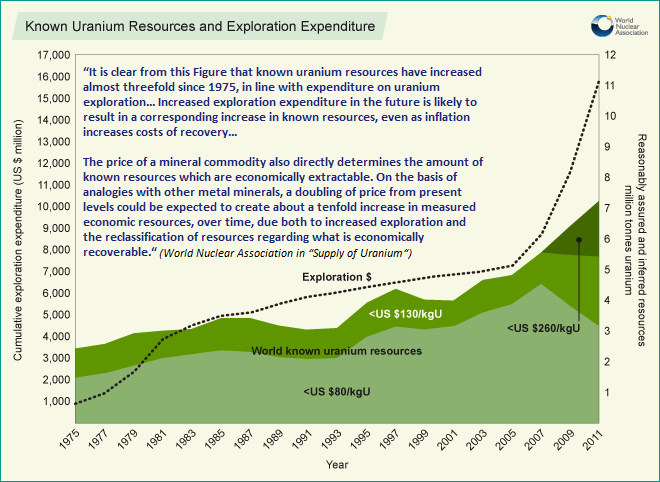

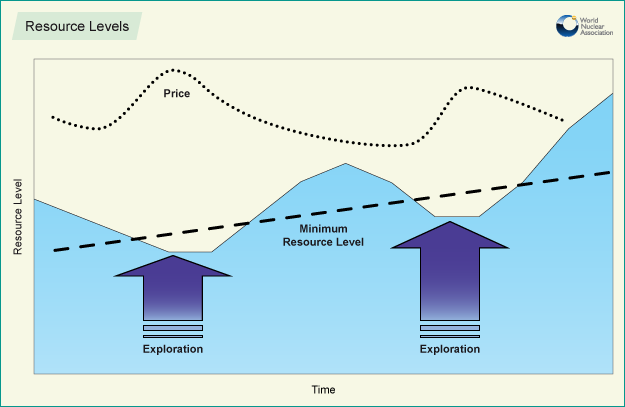

Uranium is (still) one of the few commodity markets experiencing (and thus showing investors) that increased exploration expenditures result in higher resources discovered:

Such a general, broadly manifested perception of uranium supply and demand gives us confidence in the market that vast amounts of funds are to be invested primarily into Canadian exploration – first and foremost the Athabasca Basin in Saskatchewan – during the next decades in case vast amounts of uranium are required globally. However, it is only a question of time when more uranium resources cannot be added simply by increasing exploration investments. Those few companies that today own the most prospective undeveloped properties around the Athabasca Basin are ready to thrive the most – no matter if uranium prices remain depressed, because new discoveries create new value as long as the matter has value.

As laid out in our previous articles in November and December, the Canadian Athabasca Basin is expected to become the place to be for future uranium supply. That is the reason why foreign mining companies like Rio Tinto from Australia have been forcefully trying to put a foot in that door during the last few years. Located in one of the world’s safest and most favorable mining jurisdictions, the Athabasca Basin is home to the largest and highest grade uranium mines worldwide; however most importantly, it is still largely under-explored and hosts many deposits yet to be discovered.

In the next days, we will publish an article on how investors can best profit from rising uranium prices, namely with exploration companies making new discoveries in the prolific Athabasca Basin. We will look into the aspects of what makes up a prospective property and look into other important features of a well-positioned exploration company: People, Partnerships and Structure.

Disclaimer: Neither the author nor Rockstone Research Ltd. hold equities in any of the companies mentioned herein. Neither Rockstone Research Ltd. nor the author was remunerated by any of the companies mentioned herein to produce or publish this content. Please read the full disclaimer at www.rockstone-research.com as none of this content is to be construed as an "investment advice."

- English (UK)

- English (India)

- English (Canada)

- English (Australia)

- English (South Africa)

- English (Philippines)

- English (Nigeria)

- Deutsch

- Español (España)

- Español (México)

- Français

- Italiano

- Nederlands

- Português (Portugal)

- Polski

- Português (Brasil)

- Русский

- Türkçe

- العربية

- Ελληνικά

- Svenska

- Suomi

- עברית

- 日本語

- 한국어

- 简体中文

- 繁體中文

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Bahasa Melayu

- ไทย

- Tiếng Việt

- हिंदी

Uranium: Ready To Roar Back?

Latest comments

Loading next article…

Install Our App

Risk Disclosure: Trading in financial instruments and/or cryptocurrencies involves high risks including the risk of losing some, or all, of your investment amount, and may not be suitable for all investors. Prices of cryptocurrencies are extremely volatile and may be affected by external factors such as financial, regulatory or political events. Trading on margin increases the financial risks.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

Before deciding to trade in financial instrument or cryptocurrencies you should be fully informed of the risks and costs associated with trading the financial markets, carefully consider your investment objectives, level of experience, and risk appetite, and seek professional advice where needed.

Fusion Media would like to remind you that the data contained in this website is not necessarily real-time nor accurate. The data and prices on the website are not necessarily provided by any market or exchange, but may be provided by market makers, and so prices may not be accurate and may differ from the actual price at any given market, meaning prices are indicative and not appropriate for trading purposes. Fusion Media and any provider of the data contained in this website will not accept liability for any loss or damage as a result of your trading, or your reliance on the information contained within this website.

It is prohibited to use, store, reproduce, display, modify, transmit or distribute the data contained in this website without the explicit prior written permission of Fusion Media and/or the data provider. All intellectual property rights are reserved by the providers and/or the exchange providing the data contained in this website.

Fusion Media may be compensated by the advertisers that appear on the website, based on your interaction with the advertisements or advertisers.

© 2007-2025 - Fusion Media Limited. All Rights Reserved.