The worse things seem, the better the opportunities are for profit.

Such is the very nature of investing.

Baron Rothschild, an 18th-century British nobleman and member of the Rothschild banking family, once said:

The time to buy is when there’s blood in the streets.

He should know. Rothschild made a fortune buying in the panic that followed the Battle of Waterloo against Napoleon.

Warren Buffett once said the same:

Be fearful when others are greedy, and greedy when others are fearful.

In other words, going against the crowd often yields the most successful outcomes.

This is the essence of contrarian investing.

Contrarian investors have historically made their best investments during times of market turmoil. During the crash of 1987 (also known as “Black Monday”), the Dow dropped 22% in one day in the U.S. In the 1973-74 bear market, the market lost 45% in about 22 months. The “Great Financial Crisis” of 2008 saw asset values get cut in half. The list goes on and on, but those are times when contrarians found their best investments.

But being a contrarian is extremely difficult. As Howard Marks noted:

Resisting – and thereby achieving success as a contrarian – isn’t easy. Things combine to make it difficult; including natural herd tendencies and the pain imposed by being out of step, since momentum invariably makes pro-cyclical actions look correct for a while. (That’s why it’s essential to remember that ‘being too far ahead of your time is indistinguishable from being wrong.’)

Given the uncertain nature of the future, and thus the difficulty of being confident your position is the right one – especially as price moves against you – it’s challenging to be a lonely contrarian.

Of course, behavioral analysis shows that investors always do the opposite of what they should do – they repeatedly “buy high” and “sell low.”

This is why being a contrarian is both lonely and tough.

If you could buy the stock market today at a 50% discount – would you?

Well, there is currently a glaring “contrarian” opportunity in Treasury bonds as I noted last weekend:

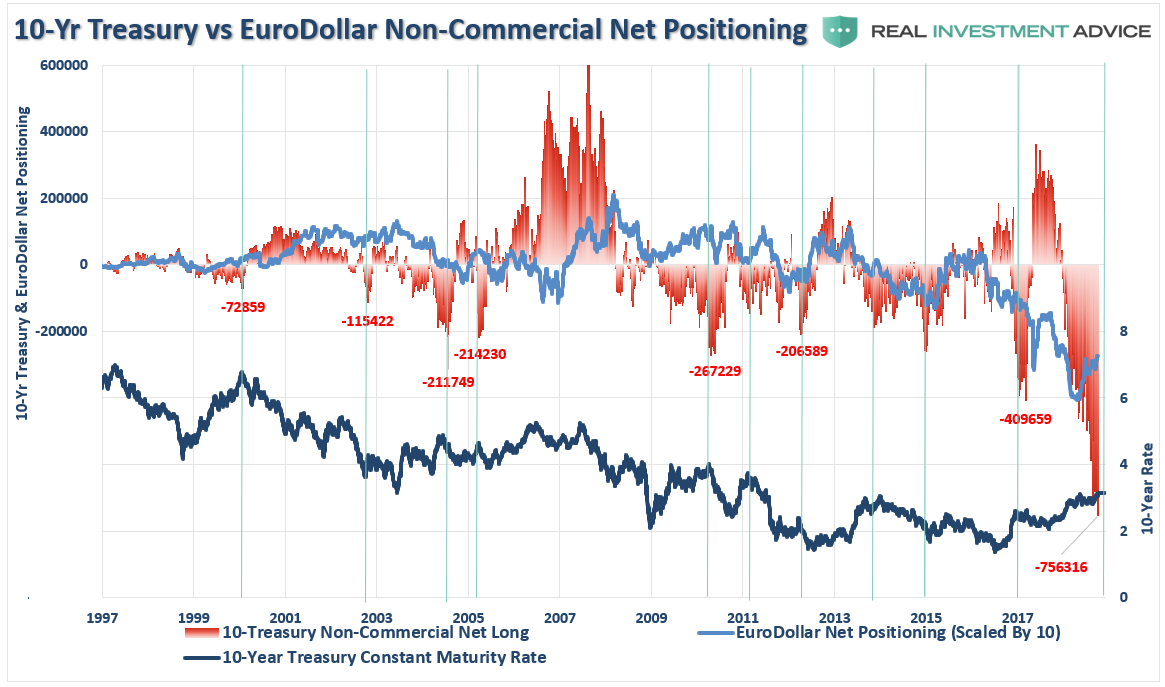

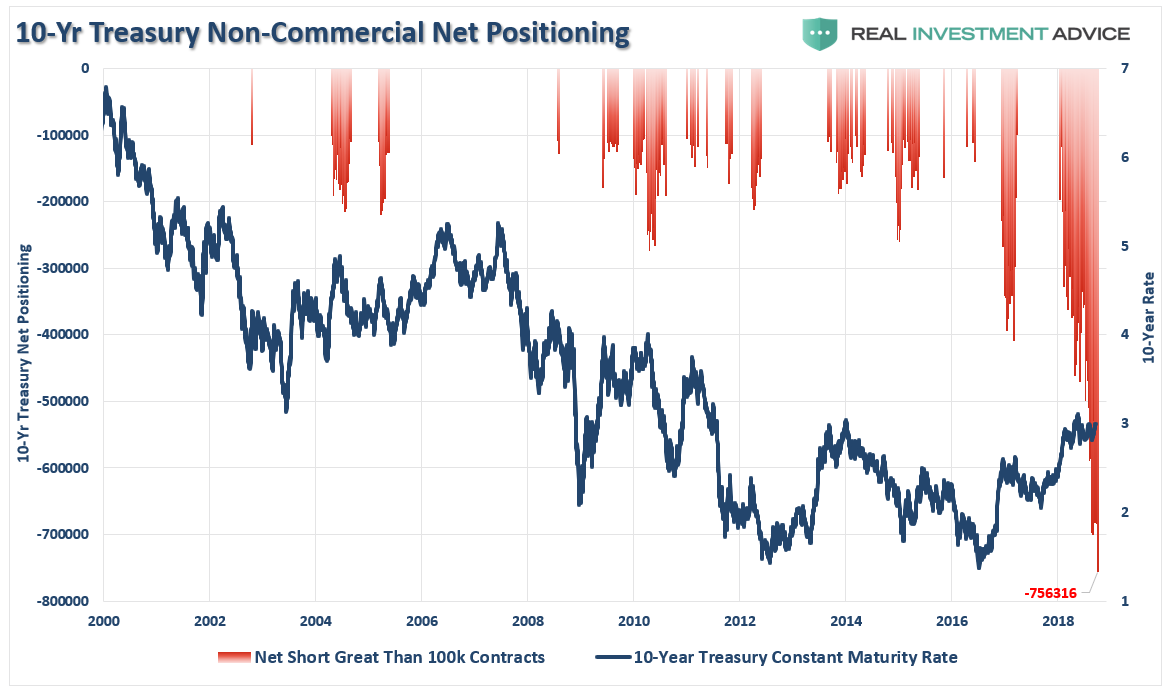

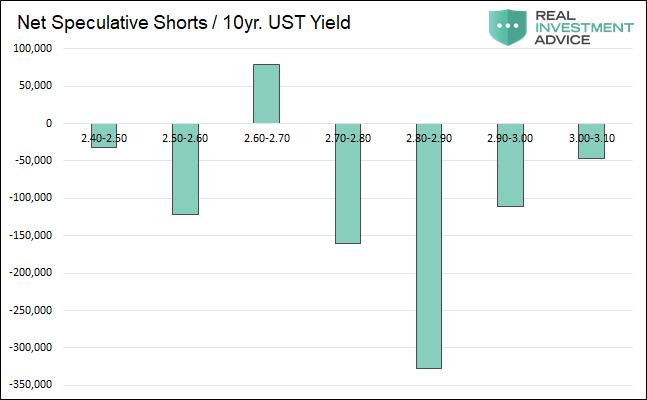

With bond traders more short than at any point in history, the ultimate “reversion to the mean” in Treasury’s will drive rates towards zero.

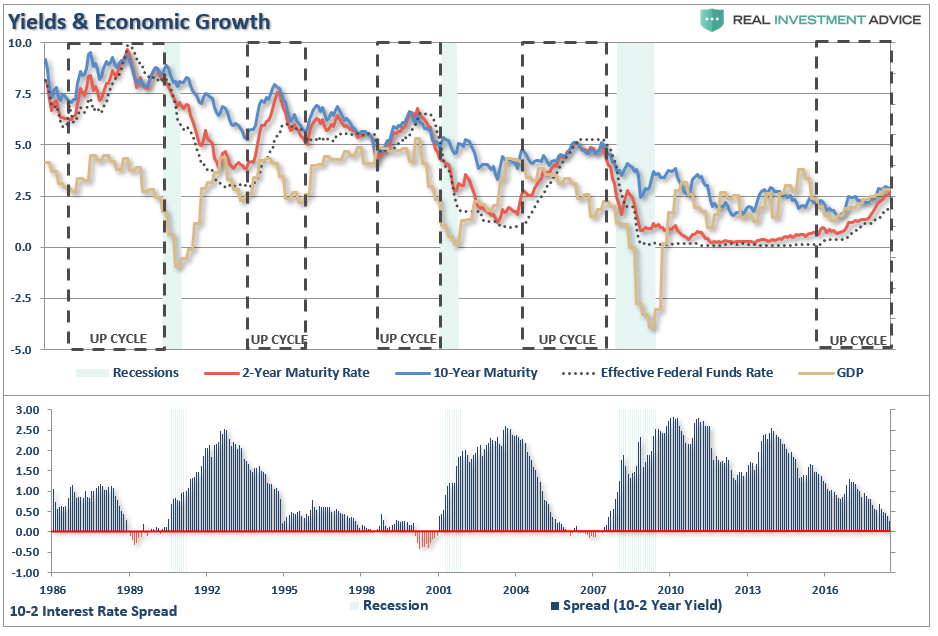

The chart below strips out all periods EXCEPT where net-short bond positions exceeded 100,000 contracts. In every case, interest rates turned lower.

But yet, despite the massive “one-sided bet on bonds,” investors can’t wait to sell.

The Great Bond Bull Market Approaches

Eric Hickman recently made “the” key observation as to why rates will fall in the months ahead:

With the economic expansion nine months from being the longest in U.S. history, the yield curve nearly flat and housing market indicators peaking earlier this year, it doesn’t take much imagination to see what’s next: a recession and falling interest rate cycle – i.e., a U.S. Treasury bull market.

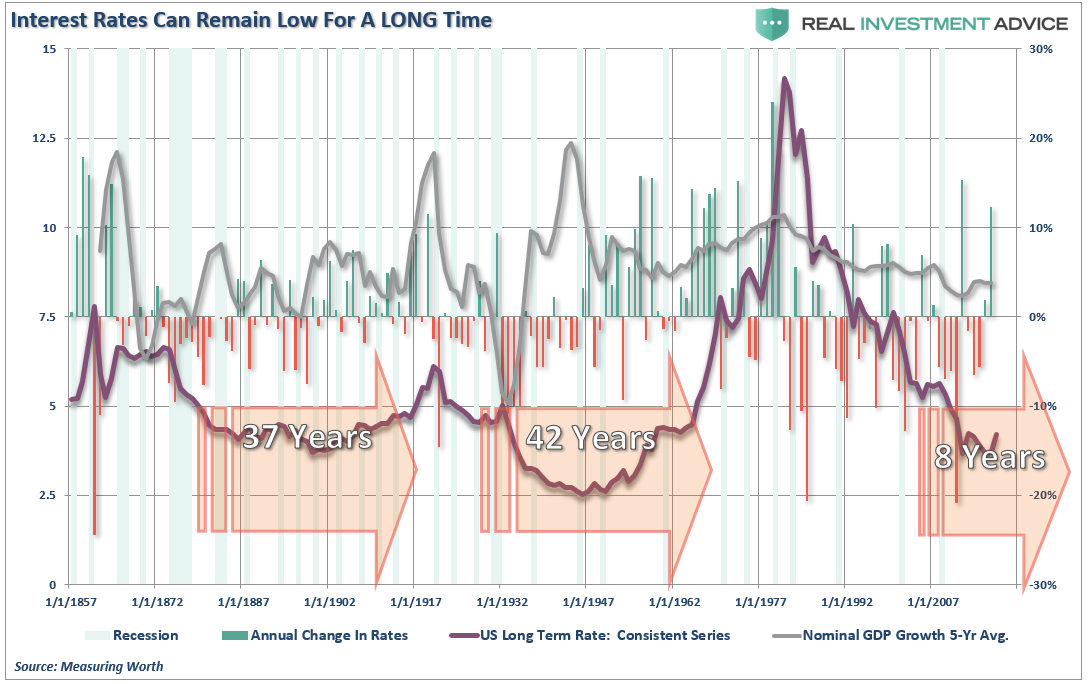

There is a very long precedent to back up his claim. The chart below, which tracks rates back to the late 1800s, shows that rates not only fall during recessions, but they can, and do, remain low for extremely long periods of time.

The premise is fairly simple.

Rising interest rates are a function of strong, organic, economic growth that leads to a rising demand for capital over time. There have been two previous periods in history that have had the necessary ingredients to support rising interest rates. The first was during the turn of the previous century as the country became more accessible via railroads and automobiles, production ramped up for World War I, and America began the shift from an agricultural to industrial economy.

The second period occurred post-World War II as America became the “last man standing” as France, England, Russia, Germany, Poland, Japan and others were left devastated. It was here that America found its strongest run of economic growth in its history as the “boys of war” returned home to start rebuilding the countries that they had just destroyed. But that was just the start of it.

Beginning in the late 50s, America embarked upon its greatest quest in history as man took his first steps into space. The space race that lasted nearly twenty years led to leaps in innovation and technology that paved the wave for the future of America. Combined with the industrial and manufacturing backdrop, America experienced high levels of economic growth and increased savings rates which fostered the required backdrop for higher interest rates.

Today, the ingredients to create that kind of economic growth no longer exists.

- The U.S. is no longer the manufacturing powerhouse it once was.

- Globalization has sent jobs to the cheapest sources of labor.

- Technological advances reduce the need for human labor and suppress wages as productivity increases.

- Labor force participation rates remain mired near their lowest levels since the 1970’s.

- Demographic trends in the U.S. continue to weigh on the sustainability of pension benefits and long-term economic growth.

- Massive debt levels divert capital from productive investment to debt service.

- Productivity growth, the engine for economic growth, has ground to a halt.

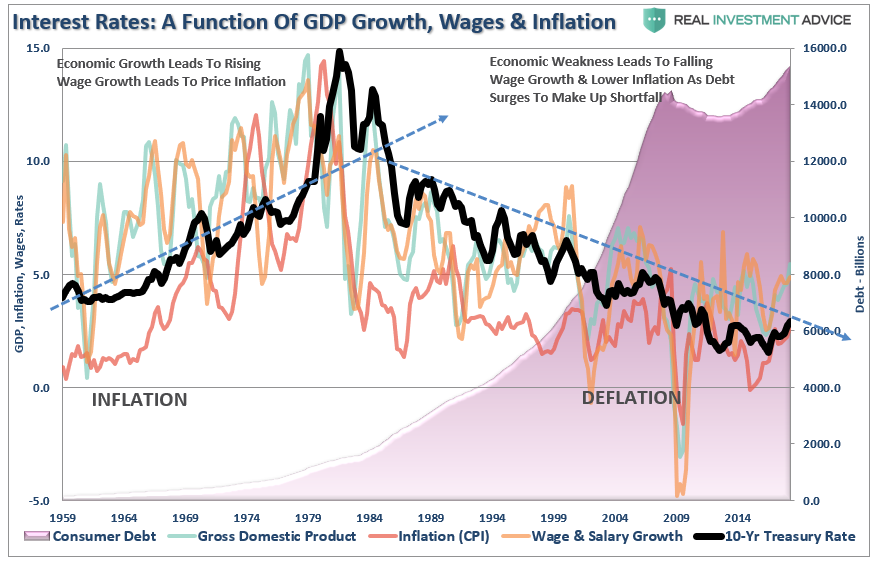

Interest rates are not just a function of the investment market, but rather the level of “demand” for capital in the economy. When the economy is expanding organically, the demand for capital rises as businesses expand production to meet rising demand. Increased production leads to higher wages which in turn fosters more aggregate demand. As consumption increases, so does the ability for producers to charge higher prices (inflation) and for lenders to increase borrowing costs. (Currently, we do not have the type of inflation that leads to stronger economic growth, just inflation in the costs of living that saps consumer spending – Rent, Insurance, Health Care, Energy.)

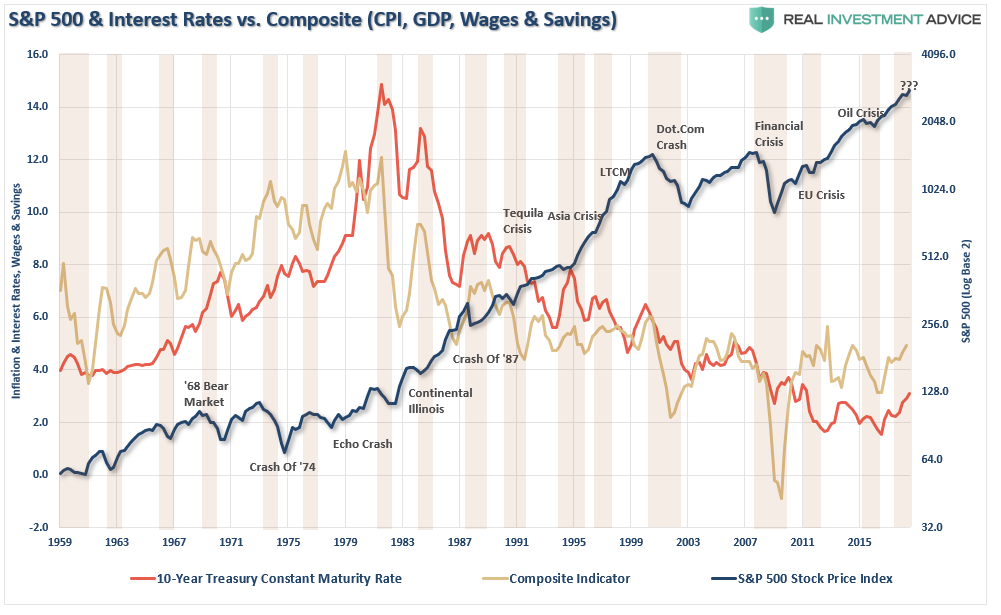

This is shown in the chart below. The rise in rates during the 60-70s was combined with rising inflationary pressures driven by a rising trend in economic growth and wages. Extremely low levels of household indebtedness allowed rates to rise without severely negative consequences.

With households, corporations, the government and investors more levered today than ever before in history, the rise in rates will have a more immediate and widespread economic consequence.

When rates start to increase, there is NOT an immediate negative consequence on economic growth, employment, or inflation. As the increase continues, early warning signs are dismissed as just a “lull” or “soft landing.” However, those early warning signs have previously been just that.

However, the problem with most of the forecasts for a continued rise in rates, along with a continued stock bull market, is the assumption that we are only talking about the isolated case of a shifting of asset classes between stocks and bonds. The issue of rising borrowing costs spreads through the entire financial ecosystem like a virus. The rise and fall of stock prices have very little to do with the average American the vast majority of whom have no stake in the markets. Interest rates, however, are an entirely different matter and has the greatest effect on the bottom 80% of the economy. Think student loans, auto loans, credit card debt and mortgages.

The chart below shows the composite economic indicator of inflation, wages, GDP, and savings as compared to interest rates and the S&P 500. Sharp upticks in rates have historically led to financial events, recessions, market corrections, or a combination of all three.

The irrationality of market participants, combined with globally accommodative central bankers, have continued to push asset values higher and concentrate investors into the ongoing “chase for yield.”

Bull markets, low unemployment, elevated consumer and investor sentiment, economic growth, and inflation are near peaks at the end of the cycle. As Eric noted:

Bull markets began far before their accompanying recession did. The bull markets started an average of 1.8 years before. This happens because the start of a recession is marked by a decline in real economic activity, yet long-term Treasury yields start to move lower from the mere hint of a slowdown in activity. This is important because many familiar commentators and banks (Ray Dalio, Ben Bernanke, Nouriel Roubini, Mark Zandi, Societe Generale (PA:SOGN), JP Morgan) are warning of a recession in 2020. This 1.8-year average combined with a mid-2020 recession would suggest a U.S. Treasury bull market beginning around now.

The majority of the speculative bond “shorts,” shown in the chart above, were put on between 2.80% and 2.90% on the 10-year Treasury. When rates approach that level, shorts will likely aggressively buy to cover their shorts and prevent loses. Such a “short squeeze” will send rates lower very quickly.

There isn’t much guessing on how this will end, and history tells us that such things rarely end well.

But this is where the opportunity currently exists for a contrarian with a longer-term view:

It is counterintuitive, but U.S. Treasury bull markets begin when the economic weather is the sunniest. It happens when the unemployment rate is the lowest and consumer and industrial confidence the highest. By the time a recession is obvious, a good chunk of the move lower in rates will have taken place. Of course, there are no hard and fast rules to make money in finance, but to the extent that ‘this time isn’t different,’ now is the time to get ready for a large opportunity in the U.S Treasury market.

I agree.

The next recession will be much larger and deeper than most currently expect due to the massive amount of leverage built up during the current cycle. A loss of 45-50% on the S&P 500 will not be surprising as a mean-reverting event wipes out a big chunk of the gains made over the last decade. Efforts by the Fed will be restricted as the pension fund crisis expands and a “debt deleveraging” cycle takes hold.

The ideal investment to take advantage of the next cycle will be Treasury bonds.

You just want to buy them while they are still cheap because once they begin to move, the reversion to the mean will be much more rapid than you can imagine.