Yes. We are in a stock market bubble. The only question is, what will be the issue that eventually pops it? We alluded to this answer in Friday’s #MacroView discussing why more “Stimulus Won’t Create Economic Growth.”

As discussed in our previous article, if market bubbles are about “psychology,” as represented by investors’ herding behavior, then price and valuations reflect that psychology.

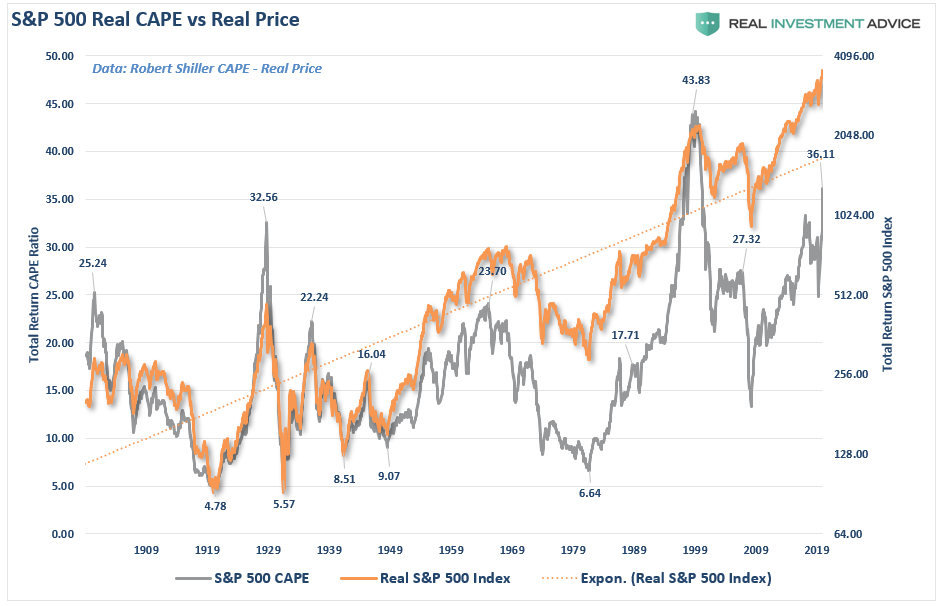

In other words, bubbles can exist even at times when valuations and fundamentals might argue otherwise. Let me show you an elementary example of what I mean. The chart below is the long-term valuation of the S&P 500 going back to 1871.

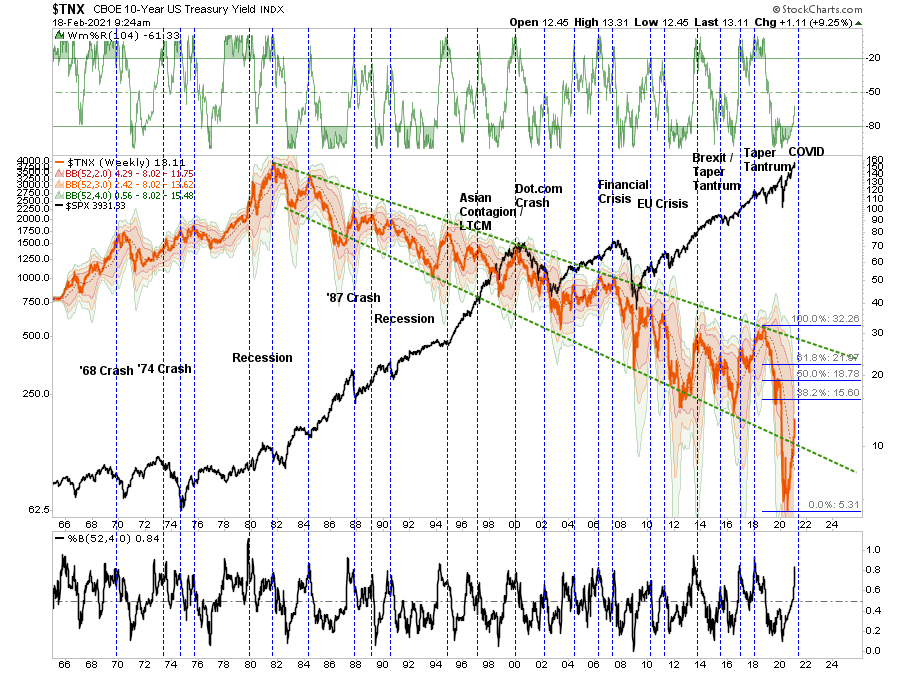

Notice that except for only 1929, 2000, and 2007, every other major market crash occurred with valuations at levels LOWER than they are currently.

Secondly, all market crashes, which resulted from the preceding bubble, have been the result of things unrelated to valuation levels. Those catalysts have ranged from liquidity issues to government actions, monetary policy mistakes, recessions, or inflationary spikes. Those events were the catalyst, or trigger, that started the “reversion in sentiment” by investors.

There are currently two “pins” that could pop the current market bubble.

The Inflation Pin

To fully explain why the Fed is now trapped, we must start with the inflation premise.

The Federal Reserve has consistently argued that monetary policy is a function of their two mandates: full employment and price stability.

While the Fed has stated they are willing to let “inflation” run hot, their biggest fear is a repeat of the runaway inflation of the 70s. However, the basis of the entire bull market thesis is low rates.

As Oliver Blanchard of the Federal Reserve recently stated concerning Biden’s $1.9 trillion stimulus package:

“How this number translates into an increase in demand this year depends on multipliers. If the average multiplier is 1 (which I think of as a conservative assumption), this implies that demand would increase by 4-times the output gap.

If this increase in demand could be accommodated, it would lead to a level of output at 14% above potential, which would take the unemployment rate very close to zero.

Such would not be overheating (i.e. inflation), it would be starting a fire.”

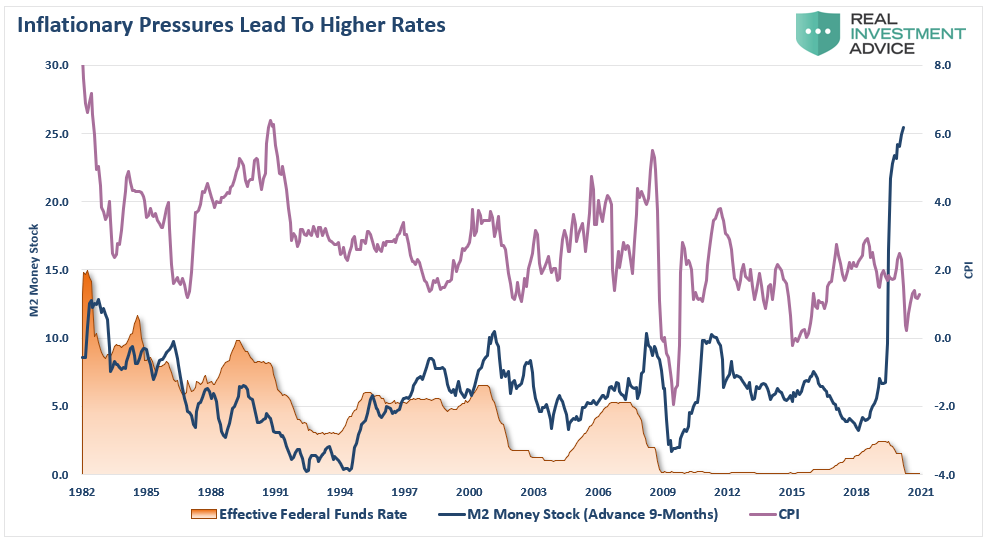

Using the money supply as a proxy, we can compare the money supply changes to inflation.

The chart below advances M2 by 9-months as compared to CPI and the Fed Funds rate. If the historical correlation holds, the Federal Reserve will start talking about tapering monetary policy, and hiking interest rates, within the next year.

Of course, the last time the Fed started discussing similar policy changes was in 2017, which lead to the great “Taper Tantrum” of 2018.

The Interest Rate Pin

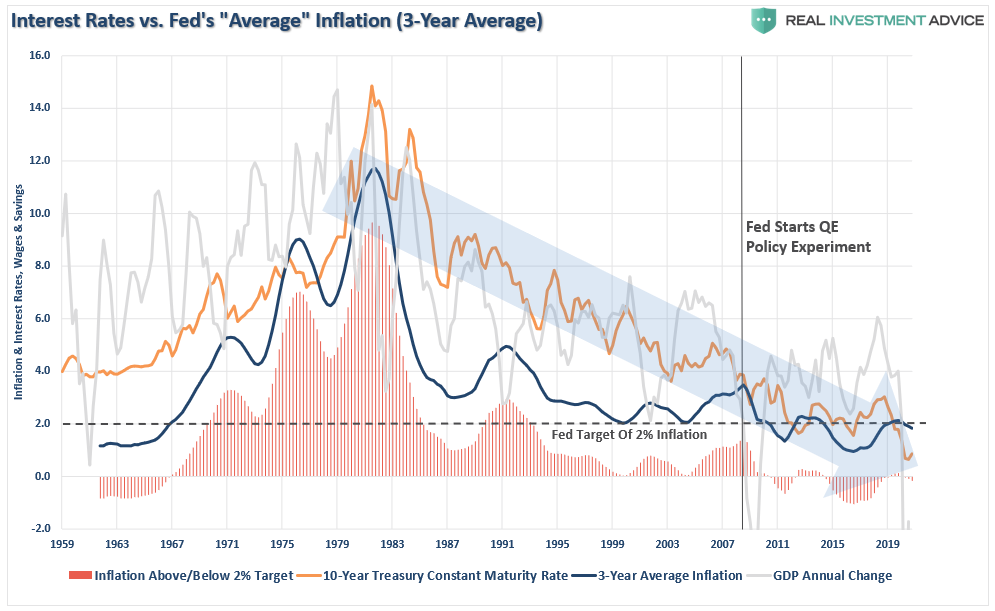

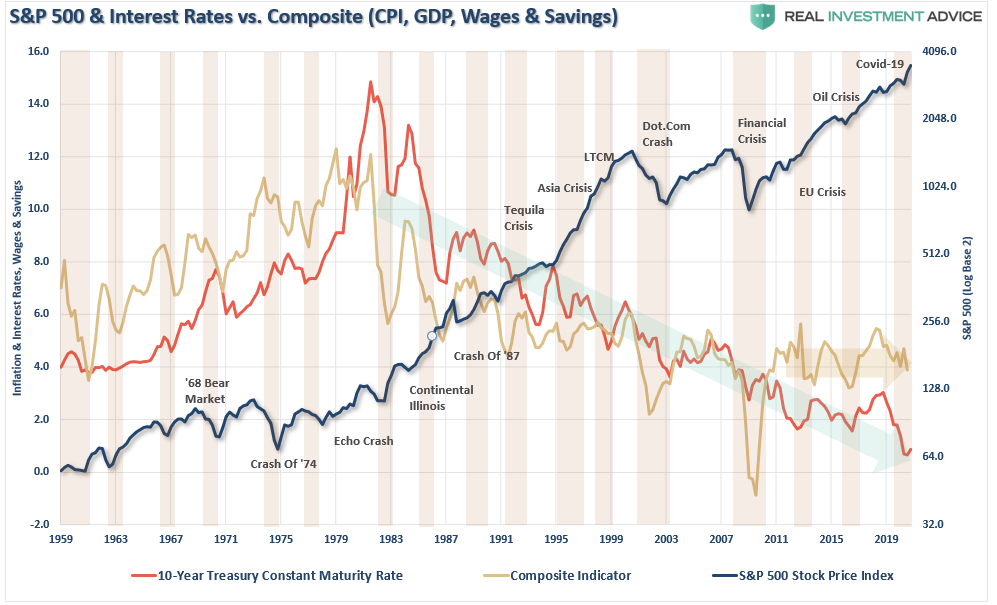

As noted, the problem with inflation is that if economists do get their wish for higher prices, such also corresponds historically with higher interest rates.

However, as you will note, each time that interest rate has moved up correspondingly with inflation, such never remained the case for long. While much of the media is currently suggesting that interest rates are about to surge higher due to economic growth and inflationary pressure, I disagree.

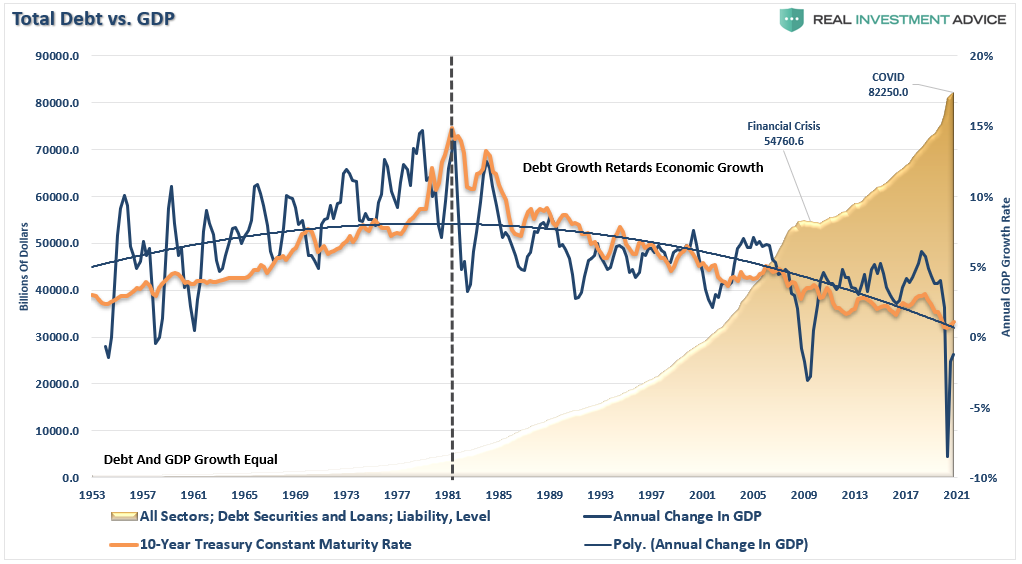

Economic growth is “governed” by the level of debt and deficits. However, it isn’t just the heavily leveraged government—it is every single facet of the economy.

Debt has exploded

In 1980, the Federal Reserve became active in monetary policy, believing they could control economic growth and inflationary pressures. Decades of their monetary experiment have succeeded only in reducing economic growth and inflation and increasing economic inequality.

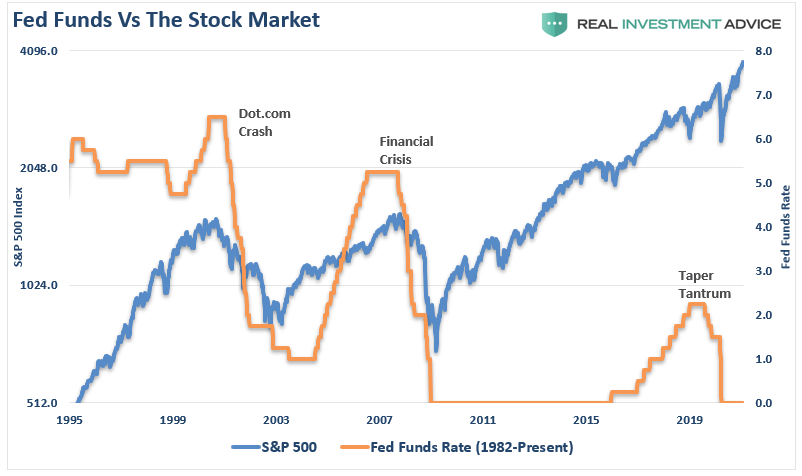

In a heavily indebted economy, increases in rates are problematic for markets whose valuation premise relies on low rates.

Each time rates have “spiked” in the past; it has generally preceded a mild to a severe market correction.

As is often stated, “a crisis happens slowly, then all at once.”

So, how did the Federal Reserve get themselves into this trap?

“Slowly, and then all at once.”

The Trap

In an economy laden with $85 Trillion in total debt, higher interest rates have an immediate impact on consumption, which is 70% of economic growth. The chart below shows this to be the case, which is the interest service on total credit market debt. (The chart assumes all debt is equivalent to the 10-year Treasury, which is not the case.)

Importantly, note that each time rates have risen substantially from previous lows, there has been a crisis, recession, or a bear market. Currently, with rates at historic lows, consumers are rushing out to buy houses and cars. However, if rates rise to between 1.5 and 2%, economic growth will quickly stall. Such was a point we made in our COT Report:

“Can rates rise in the near-term due to “checks to households” that get spent to pull-forward consumption? Absolutely.

However, the limit of that increase in rates is between 1.56% and 2.19%. At these points, rates will collide with the outstanding debt.”

The Federal Reserve is well aware of the problem. Such is why they have been quick to reduce rates and increase bond purchases, as higher rates spread through the economy like a virus.

The Rate Virus

In an economy that requires roughly $5 of debt to create $1 of economic growth, changes to interest rates have an immediate impact on consumption and growth.

- An increase in rates curtails growth as rising borrowing costs slow consumption.

- As of Jan. 21, the Fed now has $7.38 trillion in liabilities and $39.2 billion in capital. A sharp rise in rates will dramatically impair their balance sheet.

- Rising interest rates will immediately slow the housing market. People buy payments, not houses, and rising rates mean higher payments.

- An increase in rates means higher borrowing costs and lower profit margins for corporations.

- Stock valuations have been elevated due to low rates. Higher rates exacerbate the valuation problem for equities.

- The negative impact on the massive derivatives market could lead to another credit crisis as rate-spread derivatives go bust.

- As rates increase, so do the variable rate interest payments on credit cards. With the consumer already impacted by stagnant wages, under-employment, and high living costs, a rise in debt payments would further curtail disposable incomes.

- Rising defaults on debt services will negatively impact banks that are still not adequately capitalized and still burdened by massive bad debt levels.

- The deficit/GDP ratio will surge as borrowing costs rise sharply.

I could go on, but you get the idea.

Since interest rates affect “payments,” increases in rates negatively impact consumption, housing, and investment, which ultimately deters economic growth.

With “expectations” currently “off the charts,” literally, it will ultimately be the level of interest rates that triggers some “credit event” that starts the “great unwinding.”

It has happened every time in history.

No Way Out

The problem for the market going forward, as noted, is that markets have priced in a speedy recovery back to pre-recession norms, no secondary outbreak of the virus, and a vaccine. If such does turn out to be the case, the Federal Reserve will have a huge problem.

The “unlimited QE” bazooka is dependent on the Fed needing to monetize the deficit and support economic growth. However, if the goals of full employment and economic growth get quickly reached, the Fed will face a potential “inflation surge.”

Such will put the Fed into a very tight box. The surge in inflation will limit their ability to continue “unlimited QE” without further exacerbating the inflation problem. However, if they don’t “monetize” the deficit through their “QE” program, interest rates will surge, leading to an economic recession.

It’s a no-win situation for the Fed

As Doug Kass concluded last week:

“To me, there is only one inescapable economic conclusion – inflation and interest rates are heading higher as better economic growth in the last half of 2021 is delivered by the unprecedented stimulus. Unfortunately, the stimulus is in the form of mostly transfer payments and not in expansion of productivity or capacity.

The economic boom will be a sugar-based high and there is an almost inevitable bust cycle emerging by or in 2023 when the heady fiscal stimulus ends.

Today’s record stock prices belie a likely hard economic landing that may lie ahead.”

Of course, this has always been the case historically. Just as the “Coyote” still wound up going over the cliff when chasing the “Roadrunner,” excessive bullish optimism is always eventually met with disappointment.

Which stock should you buy in your very next trade?

With valuations skyrocketing in 2024, many investors are uneasy putting more money into stocks. Unsure where to invest next? Get access to our proven portfolios and discover high-potential opportunities.

In 2024 alone, ProPicks AI identified 2 stocks that surged over 150%, 4 additional stocks that leaped over 30%, and 3 more that climbed over 25%. That's an impressive track record.

With portfolios tailored for Dow stocks, S&P stocks, Tech stocks, and Mid Cap stocks, you can explore various wealth-building strategies.