Currently, some market watchers have begun to openly question whether the bull market in stocks has finally come to an end. They certainly have cause to worry. Valuations are frothy after a record run-up in the last few years. Bond yields across the yield curve are rising sharply, as the Fed Funds Rate breaks into territory not seen since before the market crash of 2008. Much higher costs of capital are already putting pressure on rate-sensitive industries such as housing and autos. The boost to earnings provided by the corporate tax cuts will fade and rising prices resulting from past monetary policy and import tariffs may be expected to slow consumption and take a toll on balance sheets. All this points to possible lackluster performance, with stocks essentially flat so far this year.

But even while many expect a difficult period for stocks, we must come to grips with the fact that generations of investors have come and gone who have not experienced a grinding and protracted bear market. Such a scenario is unthinkable given the narrative to which these investors have been exposed. But the page may about to be turned and there are reasons to believe that the bill may finally be coming due.

Falling interest rates are generally regarded as good for stocks. Not surprisingly then, since Treasury bond yields began falling in 1982 (based on data from U.S. Dept. of Treasury), stocks have trended higher. The memorable declines that we have had since then, the Black Monday Crash of 1987, the sell off after the ’90 recession, the Dotcom and September 11 implosion of 2000-2001, and the Crash of 2008, were really just interludes in an otherwise surging bull market that has risen more than 30 times in nominal terms, according to data from the World Bank. In those events, the brunt of selling happened quickly and was over before investors really knew what had happened.

In ’87, a 35% drop in the Dow occurred in just 3 months, from August to October. In ’90 an 18% fall, also in 3 months, again from August to October. In ’98, the Russian economic crisis pushed the Dow down 18% in a month, from July to August. In all these instances, stocks made new highs within two years of the initial drop, in August ’89, April ’91 and January ’99, respectively. Entering the current century, the more difficult pullbacks have occurred, but were manageable nevertheless. Beginning in January 2000, the Dow dropped 35% over a period of 33 months. It then took an additional 4 years to make fresh nominal highs. In October 2007, the Dow began falling and plunged 53% in 16 months. But after that, stocks climbed steadily and made fresh highs almost exactly four years after the bottom. (Yahoo!Finance, DJIA interactive charts)

Those who assume that these cases represent the worst-case scenarios of what we could see in the future are ignoring the brutal bear market that lasted 16 years between January 1966 and August 1982. While the nominal point drop of 18% during that time was not particularly bad, the move downward was memorable by its duration and the degree to which it was made far worse by inflation, which often approached double digits during that time.

Inflation-adjusted real values of stocks fell by a shocking 70% from 1966 to 1982. (Macrotrends Dow Jones 100 Year Historical Chart) Let that sink in. Over 16 years, the real value of stocks fell by almost three quarters! And it’s not like investors found refuge in bonds, which were also falling at that point due to the ravages of inflation and increased government borrowing. (10-year Treasury bonds hit nearly 16% in September 1981). (FRED Economic Data, St. Louis) Given how much stock and bond prices were falling in real terms, it’s surprising that the real economy didn’t implode along with it. Yes, GDP was generally sub-par during the stagflation “Malaise Days” of the 1970’s, but real GDP was positive in all but four years between 1966 and 1982, and growth averaged 2.95% over the entire period. (That’s higher than the 2.85% GDP growth has averaged since 1983). (based on data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis) That’s fairly impressive given the performance in the stock and bond markets.

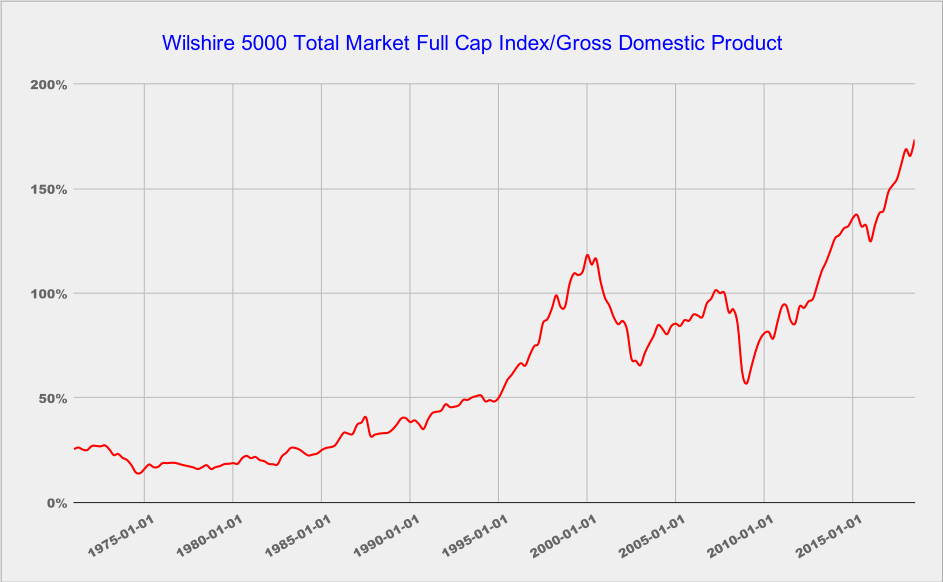

Our relatively good fortune was made possible by the fact that the market was not nearly as important to the economy then as it has become now. Back in 1966, when the market had hit a peak (after a bull run that began in the early 1950’s) (Macrotrends Dow Jones 100 Year Historical Chart), by using the Dow Jones Index’s relationship to GDP from 1966 to 1971, the year when data begins for the Wilshire 5000, we estimate that the Wilshire 5000 (the broadest measure of the U.S. stock market) would have had a collective market cap of approximately 42% of GDP, meaning that stocks were worth less than half of the whole U.S. economy. Over the next 16 years, inflation pushed up the value of just about everything consumers bought…gas, clothing, movie tickets, medical services, etc. But stock valuations lagged significantly. As a result, by 1982 the collective valuation of the stock market was only 18% of GDP. (based on data from FRED Economic Data, St. Louis)

Graph created by Euro Pacific Capital, a division of Alliance Global Partners using data from the Federal Reserve

How different the world looks today. After more than 35 years of nearly steady gains, the Wilshire 5000 is now worth 173% of the overall economy, more than four times as big, in relative terms, to where it was in 1966. I believe this did not happen by accident. What the Federal government and the Federal Reserve have done in recent years has helped push people into stocks and other financial assets, like bonds and houses. The principal driver of this has been the Fed’s overly accommodating monetary policy that can fuel inflation, divert investment into “risk” assets, and lessen the fear of losses due to a belief that the Fed will be there to pick up the pieces after a possible crash. Government deficits add to the inflation. Tax policy, corporate accounting rules, and financial technology have also added to the trend, but the big factor has always been the Fed.

The relative insignificance of the stock market in comparison to the larger economy may explain why inflation manifested itself primarily in consumer prices in the 1970’s and in financial assets more recently. The trillions of dollars created by the Fed need to go somewhere..and wherever it went it would tend to push up prices. Given the mechanism by which monetary stimuli impact the markets, it makes sense inflation has shown up primarily in financial assets. But that trend should reverse once the air comes out of the stock bubble.

When prices of stocks, bonds, and real estate go up, the “wealth effect” makes the economy appear healthier than it actually is. But beneath a veneer of strength, the real economy slowly decays. For much of our history this was not the case. The real economy could be found elsewhere, on Main Street, in factories, shipyards, warehouses, and family businesses.

As an important corollary to all this, our asset-based economy tends to favor those people who own financial assets, who tend to be wealthy. In other words, the rich have gotten richer, and those people who don’t own such assets have tended to languish. Sound familiar? The left is not wrong when they point out that these problems exist, and the right looks more and more foolish when they pretend that they don’t. Unfortunately, both sides of the political spectrum seem to favor the kinds of monetary and fiscal policies that will continue the trends rather than reverse them.

Those who argue that the more modest pullbacks of the 1990’s are more likely scenarios are not paying attention to the bond market. After Treasury bond prices rose fairly steadily for more than three decades from 1982, most analysts agree that the top of the bond market occurred in July 2016 when yields on the 10-year Treasuries hit a low of 1.37%. Since then, yields have moved up to 3.22%, the highest levels since 2011. (FRED Economic Data, St. Louis, 10-yr Treasury Constant Maturity Rate) What’s worse is that they show no signs of reversing. This could mean that the decades-old trend of rising bond prices and steadily falling yields may be over.

Given the quantity of bonds the Fed and the Treasury may need to sell to finance government deficits and to draw down the Fed’s balance sheet, record amounts of bonds could hit the market in the years ahead. But the buyers who have absorbed the inventory in the past, leveraged hedge funds, foreign central banks, and the Fed itself, may not be there to buy in quantities that will prevent yields from rising.

Stocks have not had to contend with persistently rising rates since the 1970s, and they present a clear danger to valuations. Not only do rising rates increase the cost of capital and discourage leverage, but they also give people a viable alternative to stock investment. The downside risks could be much greater than the 20% short-term bear market that the more pessimistic minds on Wall Street currently suggest, especially given the unprecedented gains we have seen in the last decade.

But what would happen to the country if the stock market entered into a protracted bear market like it did in the 1970s, a grinding downward move lasting more than a decade? What would happen if the real value of stocks fell by 50%, let alone the 90% that would be required for market capitalization to match the percentage of GDP in 1982, when the current long-term bull market began? Given the size of the stock market, and the way in which our economy has adapted to it, such declines could be devastating.

To try to stop that from happening, the Fed could cut rates to zero at the first sign of serious trouble. But that may be just the opening note of a symphony of monetary and fiscal stimulus that could last for years, if not decades. Quantitative easing might return, but this time the Fed’s purchases of bonds could be larger than they were in 2009 and 2010. The Fed might monetize the entire Federal budget deficit, which could come in at 2-3 trillions of dollars per year, if not more. It might look to buttress the housing market with trillions of dollars per year of mortgage bond purchases. And next time, QE activity might include stock market purchases in order to support the equities markets.

And while these activities may put a nominal floor under asset prices, the massive increase in money supply could unleash much higher inflation across the broader economy, pushing stock prices down in real terms just as they did from 1966 to 1982. In real terms, the rich may not be as wealthy. While this outcome may please progressives, it would also mean that the tax base would dry up, and help cause already ballooning deficits to go up that much faster. The resulting inflation could be expected to be felt most heavily by the poor, and elderly living on fixed incomes.

All this could mean that the driving policy goals of the coming decade would be to keep asset prices from falling. While the government can not be successful in this endeavor (in real terms), it would be successful in helping destroy confidence in the dollar. This should inspire those with some forethought to look for investments to hedge such a scenario. The window of opportunity to make such a shift may soon close.