Stock investors have made a “hop of hope” since the election of Donald J. Trump. Specifically, the new administration’s dedication to the repatriation of foreign profits, the lowering of corporate-tax rates and the reduction of onerous regulations may create impressive wage growth as well as momentous economic growth.

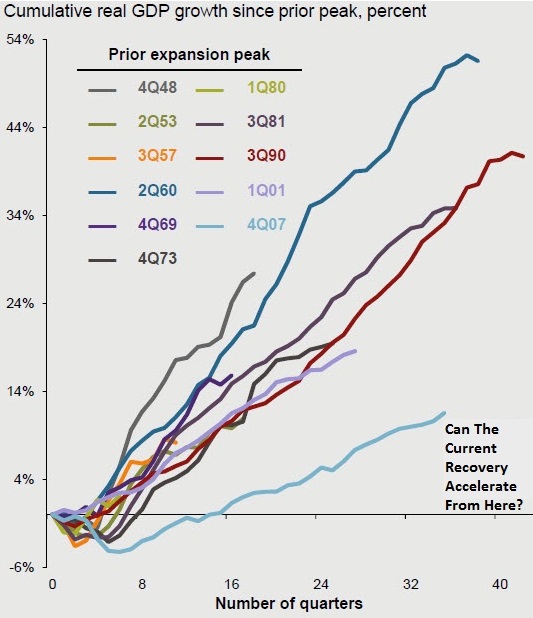

Keep in mind, year-over-year wage growth and annual GDP growth during the nearly eight years of recovery fell way short of pre-Great Recession growth rates. Wages have grown at a sub-par 2.25%; GDP has served up a disappointing 2% over the same period. And this all came with nearly $10 trillion in federal spending along with close to $4 trillion of Federal Reserve spending. That’s an amazing amount of stimulus with shockingly limited improvement. (See chart below.)

Based on what the new administration will be able to achieve through government stimulus, is the “hop of hope” by stock investors warranted? Can the Trump/Congress implement targeted fiscal measures in the mammoth size necessary to achieve genuine growth? With an immediate impact here in 2017?

It is difficult to believe that it will proceed smoothly.

Let’s take step back to the Great Recession (12/07-5/09). The United States Federal Reserve dropped its overnight rate to 0%, and left it there for seven years (12/08-12/15). Additionally, it electronically printed dollars to buy bonds, pushing borrowing costs down to their lowest levels on record. This has been great for corporations to borrow on the ultra-cheap as well as to plow the money back into repurchasing stock shares. It was great for stock investors who benefited from the significant decrease in the supply of shares as well as a relatively healthy demand for them. And it was wonderful for homeowners who wished to refinance their properties, not to mention any household/business/group that wanted to leverage to acquire more real estate.

However, zero percent rate policy (ZIRP) began losing its punch. What’s more, central banks have been trying to get out of the quagmire associated with leaving rates too low for too long; that is, reflating stock and real estate prices through manipulative and unconventional means has led to “bubbly” valuations that make fundamental analysts cringe.

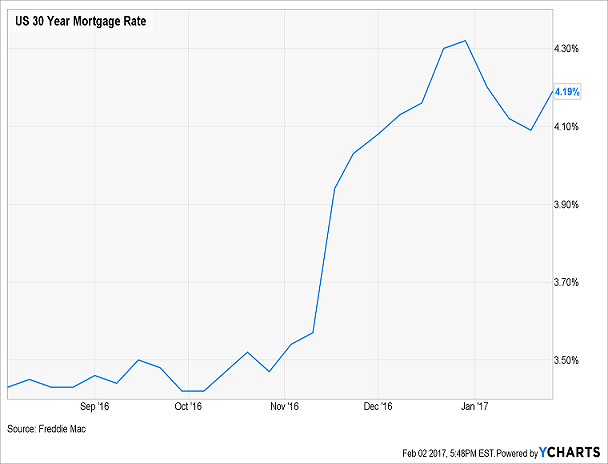

So now we have leaders at the Federal Reserve chattering about taking the 0.5% interest rate up to 1.25% by year-end 2017. Some are even talking about selling the bonds that they have on their balance sheet and/or not reinvesting the proceeds of maturing bonds. This type of “tightening talk” does two things: (1) It leaves the economic ball largely in the Trump Administration’s court -- a team that must deliver results based on a prescription (e.g., infrastructure spending, tax cuts, regulatory overhaul, trade renegotiation, etc.) that may not be powerful enough in size or timing, and (2) It leaves open the possibility for further spikes in key borrowing rates -- rates like the 30-year mortgage that have already pole vaulted three-quarters of a percentage point since last summer.

On the latter point, I do not think that investors have to fret over ever-surging yields. For starters, Trump is likely to get a coalition of a Republicans and Democrats together to push the debt-ceiling debate well into the future. His pick for Treasury Secretary, Steve Mnuchin, has already indicated a desire to raise the debt ceiling and/or do whatever is necessary to avert a crisis.

(Note: The debt limit legal issue had been pushed off to mid-March of 2017 and it is relatively clear that extremely conservative Republicans will not persuade enough folks to maintain a hard-n-fast debt ceiling in and around $20 trillion. Not with Trump’s highly popular infrastructure spending plans and the need for some public funding of those projects.)

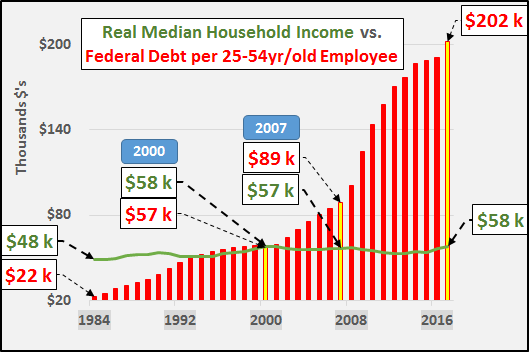

Second, the higher the debt ceiling goes, the higher the public's obligation goes, which means yields need to be lower for interest servicing. Other than hedge fund bond bears who are looking for big-time shorting opportunities, the bond bull market cannot end in earnest. Not when the Federal debt-per-prime-working-age (25-54) employee is practically choking the country to death. Yes, debt kills, but it will kill us slower if rates are kept from rising to unsustainable payback levels.

Some believe that the 2nd half of 2017 will be an endless parade of debt ceiling negotiations between a Republican-controlled Congress and a resolute minority party of Democrats. I don’t see it. If Trump himself were a fiscal conservative, things might be different. He’s not. He wants to spend government dollars (e.g., defense, infrastructure, wall, etc.) and he will get politicians from both parties to sign onto debt-ceiling increases.

Back to the world of bonds, then. If the debt ceiling is going to catapult from $20 trillion to $23 trillion in the next two years -- and I think that's a high-probability scenario -- is there any reason to think the powers-that-be would tolerate significantly higher bond yields that could kill real estate AND push interest payments on federal debt through the roof?

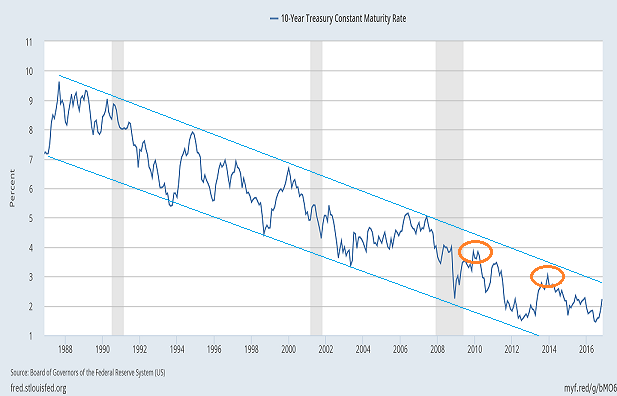

I have been actively involved in stocks and bonds and financial securities since 1986. For as long as I have been working in financial services and/or listening to those who work in financial services, I have heard the line, “The bond bull is dead! Rates can only go up!” And for three decades, that call has been premature, if not completely wrong, over and over.

Could I rethink this premise? One would need to see a meaningful breakout for the 10-year Treasury bond yield above 3% -- a breakout that establishes a sustainable floor for the government obligation.

Bond investors should view the 10-year at 2.5% as relatively reasonable. If inflation is in the neighborhood of 1.7%, a real return of 0.8% is better than many would think. I read somewhere that when the 10-year yield logged 13% in the early 1980s, inflation was close to 15%; the real (adjusted) rate of return here was -2.0%.

In other words, a 0.8% real rate of return might not be so bad after all. And if the 2.5% 10-year yield were to drop back down to new lows between 1%-1.25%, a trader might take some of that double-digit capital appreciation off the proverbial table.

One could look at iShares 7-10 Year Treasury (NYSE:IEF) here. Others who agree that 10-year yields are NOT likely to surpass 3% and/or will stay near 2.5% or move lower, might pursue the 5.5%-6% yields in preferreds. Take a look at PowerShares Financial Preferred (NYSE:PGF).

What about stocks, though? Historically speaking, price downturns for stock assets tend to be associated with one or more of these types of threats: (a) Deteriorating economic cycles, (b) Inflation, (c) Political and/or financial instability, (d) Tighter borrowing costs, and (e) Asset valuation extremes. The only “absolute” in this list right now? Asset valuation extremes.

One might think that the valuation issue alone is irrelevant. And it has been for several years now. That said, gross domestic product (GDP) for calendar year 2016 was weak at 1.6%. Inflation, while still mild, has picked up considerably over the previous 12 months. The euro-zone faces political uncertainty, particularly in Italy; China is dealing with dangerous financial leverage as well as currency concerns. And tighter borrowing costs? I may think that these have stabilized, but the Federal Reserve may decide to raise overnight lending rates at a quicker pace, if only to have ammunition to fight a future recession.

For most of my growth-and-income clients, I continue to maintain a slightly lower allocation to equities than I might otherwise have in an early-stage bull. 70%-75% equity today? Eight years later? Not a chance. 50%-60% depending on the client. And most of the assets are in higher quality stocks and/or dependable index ETFs. Take a look at iShares Quality Factor (NYSE:QUAL) and iShares Russell 1000 (NYSE:IWF).