Recently, Ed Yardeni discussed his view of why another “Roaring 20’s” may lie ahead. However, while I certainly can appreciate his always “bullish optimism,” there is a significant fundamental problem with his view.

The Reasoning

We can sum Ed’s view up in the following quote:

“There’s certainly a precedent for our current times in the past, one that was truly unprecedented back then.

World War I was followed by the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918, which infected an estimated 500 million people and killed as many as 50 million. Given that the world population was 1.8 billion back then, that implied a 28% infection rate and nearly a 3% death rate. Both stats are currently significantly lower for the COVID-19 pandemic. Today, the global population is 7.5 billion. There have been 20 million cases and 735,000 deaths worldwide as of yesterday.

The good news is that the bad news during the previous precedent was followed by the Roaring Twenties. So far, the 2020s has started with the pandemic, but there are plenty of years left for the prosperous 1920s to become a precedent for the current decade. If so, the driver of the coming boom will be technology-enhanced productivity, as it was during the 1920s.”

While the reasoning certainly seems sound, there are vast fundamental differences between today and 1920, which will likely render the analysis mute.

The Fundamental Problem Of Technology

Let’s start with the impact of Technology. As Ed notes:

“Technological progress always confounds the pessimists by solving scarce-resource problems. It also fuels productivity and prosperity, as it did in the 1920s and could do again in the 2020s.”

He is correct that technology will continue to evolve and impact society in numerous ways. However, there is a fundamental difference between the impacts of technology in the 1920s and today.

As he notes, the rise of automation and the automobile’s development had vast implications for an economy shifting from agriculture to manufacturing. Henry Ford’s innovations changed the economy’s landscape, allowing people to produce more, expand their markets, and increase access to customers.

Technological advances led to increased demand, creating more jobs needed to produce goods and services to reach those consumers.

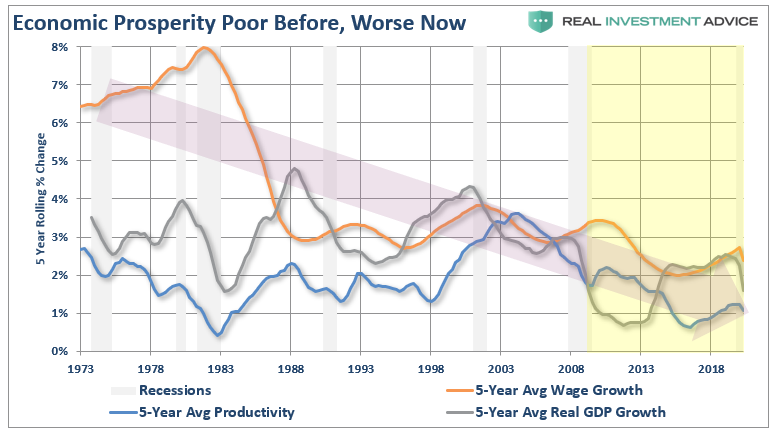

Conversely, the use of technology today reduces the demand for physical labor by increasing workers’ efficiencies. Since the turn of the century, technology has continued to suppress productivity, wages, and, subsequently, the rate of economic growth.

Technologies Dark Side

Such was a point we made in “The Rescues Are Ruining Capitalism.”

“However, these policies have all but failed to this point. From ‘cash for clunkers’ to ‘Quantitative Easing,’ economic prosperity worsened. Pulling forward future consumption, or inflating asset markets, exacerbated an artificial wealth effect. Such led to decreased savings rather than productive investments.”

The critical distinction between the technology of the ’20s and today is stark.

When technology increases productivity and output while simultaneously increasing demand by increasing “reach,” it is beneficial.

However, when technology improves efficiencies to offset weaker demand and reduce labor and costs, it is not.

Given the maturity of the U.S. economy and the ongoing drive for profitability by corporations, technology will continue to provide a headwind to economic prosperity.

The Fundamental Problem Of Debt

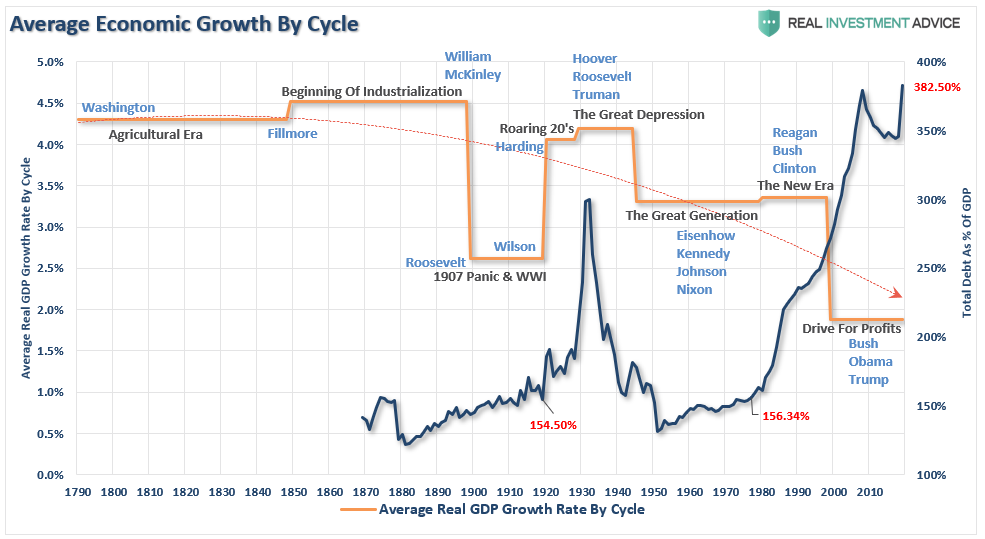

Another difference is the level of debt. One of the fundamental requirements for creating strong economic growth rates is low levels of leverage. In the 1920s, consumers had very little, if any, debt. Such was also the case with Government debt. Such allowed higher economic growth rates and overall prosperity as incomes did not get diverted to service debt.

At the beginning of the “Roaring 20s,” total credit market debt to GDP was 154%. Such was also about the same level of debt-to-GDP when we entered into the “Roaring 80’s” bull market.

Importantly, when talking about “bull markets,” the amount of debt in the system plays an essential factor. The last time that debt-to-GDP ratios hit such a peak was going into the “Great Depression.” Not the beginning of the “Roaring 20s.”

The Fundamental Problem Of Economic Growth

Since debt retards economic growth by diverting savings into debt payments rather than productive investments, such also provides a significant headwind to Ed’s “Roaring 20s” aspirations.

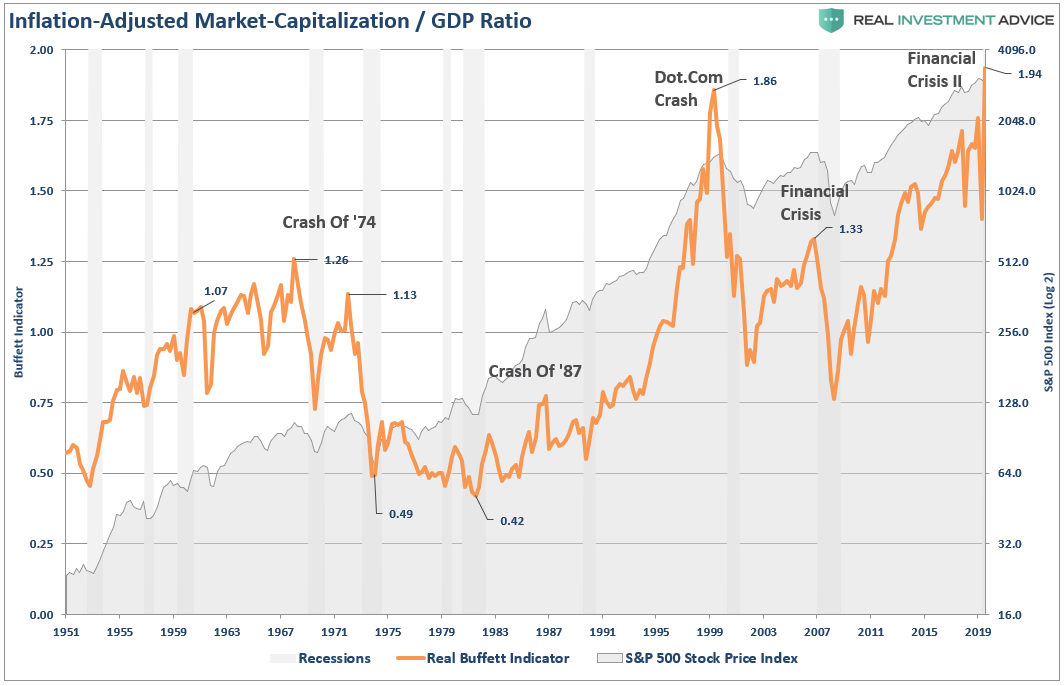

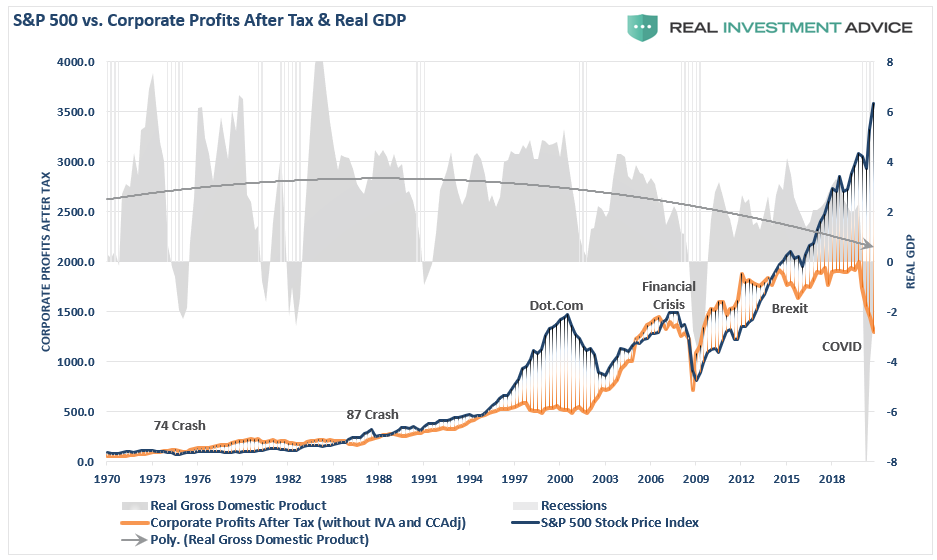

The current deviation between the market and underlying economic growth is the largest in history. Given the high correlation between the economy, corporate profits, and stock prices over the long-term, the “Market Capitalization” to “Gross Domestic Product” ratio tells us much.

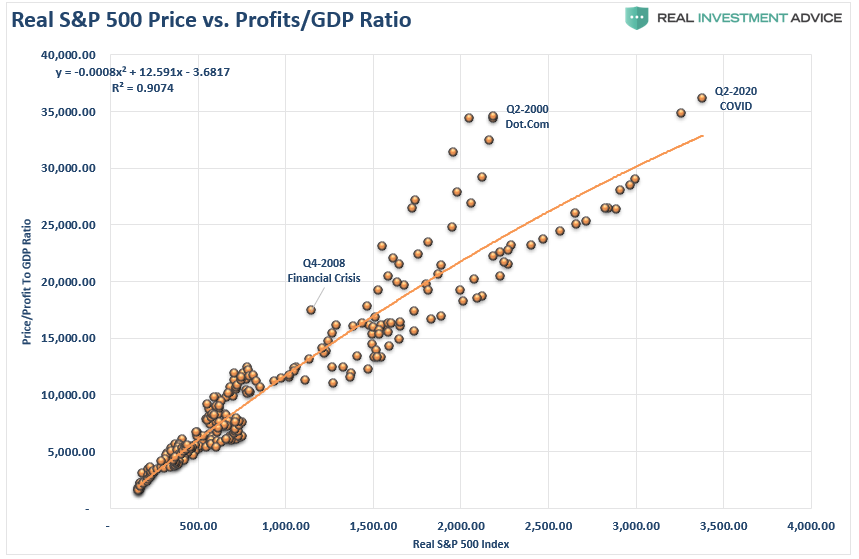

The indicator shows us that when “disconnects” between market participants and the underlying economy occur, a reversion ensues. The correlation is more evident when looking at the market versus the ratio of corporate profits to GDP. With a 90% correlation, investors should not dismiss these deviations.

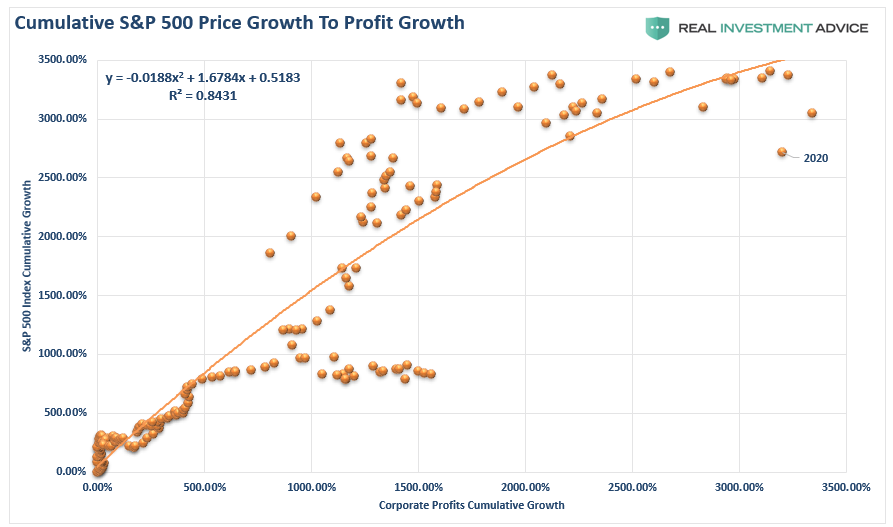

There is additional confirmation with an 84% correlation between the S&P 500 and corporate profits growth.

Since corporate profits are a function of economic growth, the correlation is not unexpected. Hence, neither should the impending reversion in both series. The current detachment would not exist without the Fed’s largesse.

Poor Future Outcomes

When it comes to the state of the market, corporate profits are the best indicator of economic strength. The detachment of the stock market from underlying profitability guarantees poor future outcomes for investors. But, as has always been the case, the markets can certainly seem to “remain irrational longer than logic would predict.”

However, such detachments never last indefinitely.

“Profit margins are probably the most mean-reverting series in finance. If profit margins do not mean-revert, then something has gone badly wrong with capitalism. If high profits do not attract competition, there is something wrong with the system, and it is not functioning properly.” – Jeremy Grantham

As opposed to Ed’s view of a surging market ahead, the reality is the current detachment of the market from the economy guarantees investors a poor outcome in the future. As we showed in “Do, You Feel Lucky:”

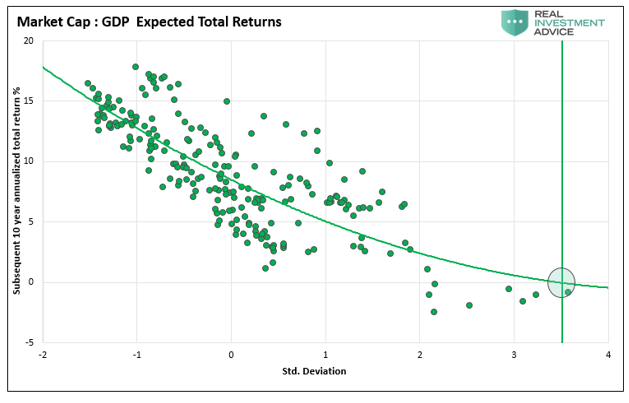

“Currently, the ratio is near 1.50, or more than twice the historical average. The only other time it was this high was in the first quarter of 2000, as the tech bubble was bursting. As shown, the expected annualized return for the next ten years is 0%.”

Such an outcome will undoubtedly be disappointing.

The Fundamental Problem Of Valuations

“The stock market is NOT the economy. But the economy is a reflection of the very thing that supports higher asset prices – corporate profits.” – Investors Are Walking Into A Trap

Lastly, given the understanding of the relationship between the economy and the stock market, the idea that stocks will remain permanently detached from fundamentals is unlikely. Importantly, Ed’s view of markets entering into another “20s era” misses the point of valuations.

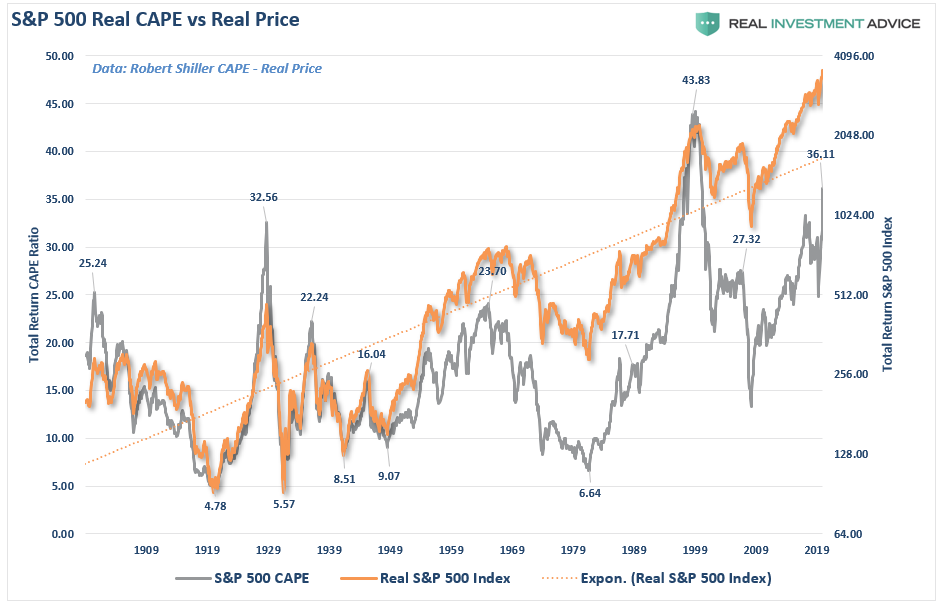

As shown, in 1920, stock market valuations were less than 5x earnings.

Context is critical. Those low valuations, and subsequent market surge, followed a nearly 20-year long bear market in stock prices. Such was due to a banking crisis in 1907, WWI, and a rarely discussed “economic depression” heading into 1920. Low valuations, combined with a depressed economy, lead to a massive recovery driven by sharply higher economic growth over the next 9-years.

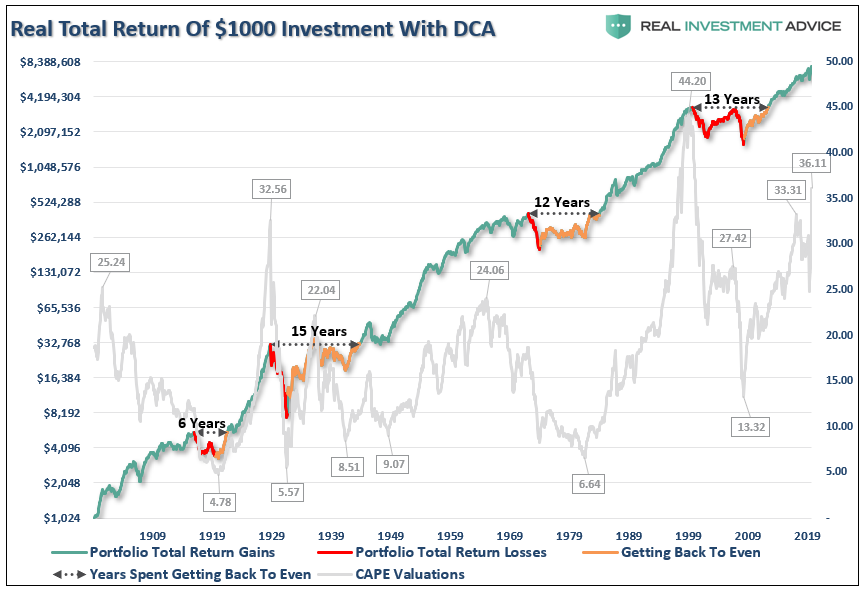

Such is hardly the case today. After an 11-year expansion, extreme leverage of the financial and economic systems, and valuations elevated, support for a 20’s melt-up is limited. As shown below, such periods have not coincided with a subsequent decade of “roaring asset prices,” but rather a disappointment.

The 20’s Analogy May Be Misguided

While the idea of a “roaring 20s market” is undoubtedly optimistic, it is also a dangerous concept for investors to “buy” into.

As stated above, the stock market, over the long-term, reflects the underlying economic activity. Personal consumption makes up roughly 70% of that activity. Given that consumers are more leveraged than at any previous historical period, it is doubtful they will become a significantly larger chunk of the economy. As such, the capacity to re-leverage to similar extremes is no longer available.

Let’s also not forget the singular most important fact.

Our history’s previous secular bull markets grew from extreme under-valuations, washed-out financial markets, and extremely negative sentiment.

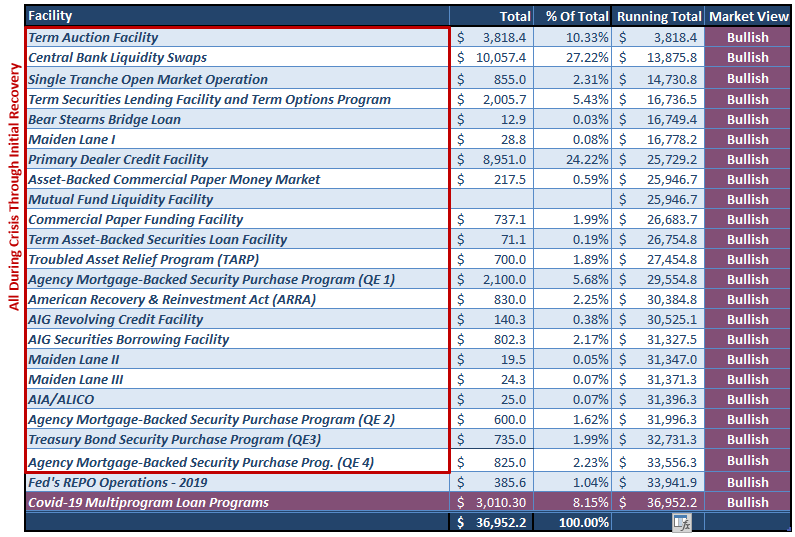

Such was not the case over the last decade as the Federal Reserve and Government have pumped more than $36 Trillion into the economy to keep it “afloat.”

I say “afloat” rather than “growing” because, during the last decade, economic “growth” was a function of population growth. Monetary interventions were successful in creating inflation in financial assets. However, during the same period, the economy grew by only $2.92 Trillion.

In other words, for each dollar of economic growth since 2008, it required $12.67 of monetary stimulus. Such sounds okay until you realize it came solely from debt issuance.

Conclusion

The “secular bull market” of the 1920s is probably the best example of the cycle we are likely ending, not beginning.

In 1920, banks were lending money to individuals to invest in the securities they were bringing to market. Interest rates were falling, economic growth was rising, and valuations grew faster than underlying earnings and profits.

There was no perceived danger in the markets and little concern of financial risk as “stocks had reached a permanently high plateau.”

It all ended rather abruptly.

Today, while stock prices can be lofted higher by further monetary tinkering, the underlying fundamentals are inverted. The larger problem remains the economic variables’ inability to “replay the tape” of the ’20s, the ’50s, or the ’80s. At some point, the markets and the economy will have to process a “reset” to rebalance the financial equation.

In all likelihood, it is precisely that reversion which will create the “set up” necessary to begin the “next great secular bull market.” Unfortunately, as was seen at the bottom of the market in 1974, there will be few individual investors left to enjoy the beginning of that ride.