Gold is one of the rarest elements in the world, making up roughly 0.003 parts per million of the earth’s crust. (For some perspective, one part per million, when converted into time, is equivalent to one minute in two years. Gold is even rarer than that.) If we took all the gold ever mined—all 186,000 tonnes, from the bullion at Fort Knox to India’s bridal jewelry to King Tut’s burial mask—and melted it down to a 20.5 meter-sided cube, it would fit snugly within the confines of an Olympic-size swimming pool.

The yellow metal’s rarity, of course, is one of the main reasons why it’s so highly valued across the globe and, for most of recorded history, recognized and used as currency. Unlike fiat money, of which we can always print more, there’s only so much recoverable gold in the world. And despite the best efforts of alchemists, we can’t recreate its unique chemistry in a lab. The only way for us to acquire more is to dig.

But for how much longer?

Goldman Sachs) analyst Eugene King took a stab at answering this question last year, estimating we have only “20 years of known mineable reserves of gold.”

The operative word here is “known.” If King’s projection turns out to be accurate, and the last “known” gold nugget is exhumed from the earth in 2035, that won’t necessarily spell the end of gold mining. Exploration will surely continue as it always has—though at a much higher cost.

(In fact, our insatiable pursuit of gold might one day soon take us to space, as President Barack Obama signed legislation in November that permits commercial mineral extraction on asteroids and the moon.

Many near-Earth asteroids are said to contain trillions of dollars’ worth of precious metals and other minerals. But that’s a discussion for another time.)

We’ll probably see a surge in mergers and acquisitions, as I told Kitco News’ Daniela Cambone last week. I think that as long as they have reliable output, mid-cap companies could be gobbled up by the Barricks and Newmonts of the world.

Another consequence of recovering the last known nugget? The gold price could spike dramatically to levels only imagined. My colleague Jim Rickards, in his book “The New Case for Gold,” puts it at $10,000 an ounce. GoldMoney founder James Turk says it’s closer to $12,000. There’s really no way of knowing how high gold could go.

Did Gold Production Peak in 2015?

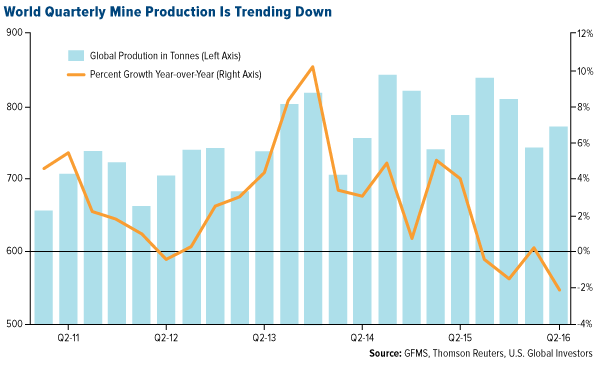

What we do know is that global gold output has been contracting since 2013. Last year might have been the tipping point, however, in line with Goldcorp CEO Chuck Jeannes’ prediction that peak gold was within spitting distance.

“There are just not that many new mines being found and developed,” he told the Wall Street Journal in 2014, adding that this was “very positive” for the gold price going forward.

This year, second-quarter mine supply was 2 percent less than the same period in 2015, according to preliminary estimates made by Thomson Reuters GFMS. Some analysts now expect global production to fall 3 percent in 2016, after seven straight years of growth.

What’s more, few new projects and expansions are expected to come online this year, writes Thomson Reuters, “and those in the near-term pipeline are generally fairly modest in scale, hence our view that global mine supply is set to begin a multiyear downtrend in 2016.”

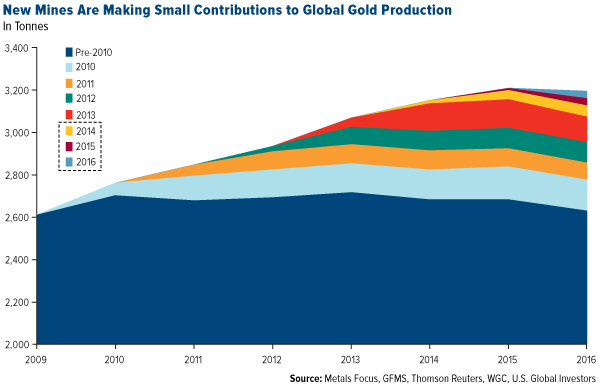

Indeed, if we look at projects that opened in just the last two or three years, we see that they’re of lower grade, meaning they don’t produce nearly as much as older, easy-to-mine gold deposits.

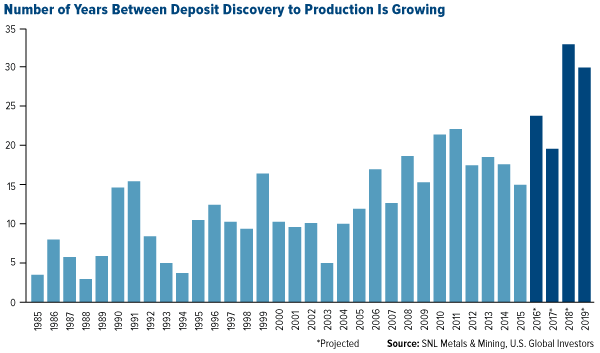

The truth of the matter is, when it comes to discovering new gold deposits, the low-hanging fruit has likely already been picked. Gone are the days when someone could stumble upon an exposed hunk of gold at the bottom of a riverbed, as James Marshall did in 1848, setting off the California Gold Rush. Every year, the pursuit of gold becomes increasingly more challenging—not to mention more expensive—requiring ever more sophisticated tools and technology, including 3D seismic imaging, direction drilling and airborne gravimetry. (A satisfactory “gold fracking” method, however, seems unlikely to become reality any time soon.)

Compounding the issue is the fact that the number of years between discovery of a new major deposit and production is widening, due to the increase in feasibility assessments, compliance, licenses and more—and that’s all before nugget one can be extracted. The average lead time for gold mines worldwide is close to 20 years, though it can sometimes be more, depending on the jurisdiction. This highlights the need for worldwide policy reform to remove many of the barriers that obstruct responsible mining.

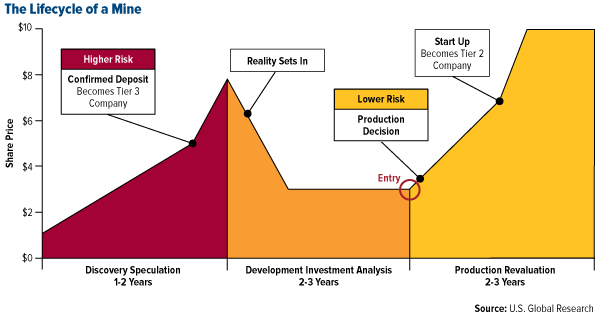

In The Goldwatcher, the book I co-wrote with John Katz, I expressed the importance of knowing which developmental stage of a mine’s lifecycle a project currently falls into, as this has a strong influence on stock performance. Investing, like life, is all about managing expectations.

Few New Mines as Companies Deleverage

What all of this means is we’ll probably continue to see fewer and fewer major discoveries, or those that yield more than a million ounces.

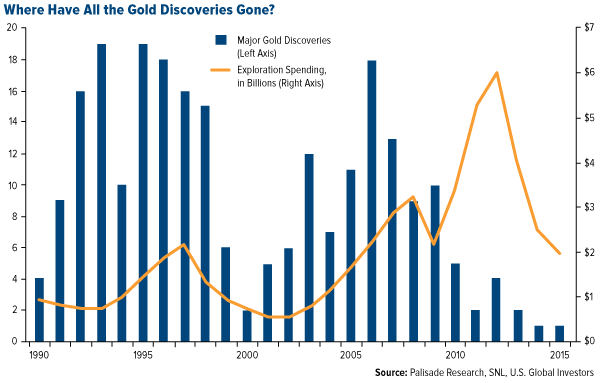

As you can see below, new gold discoveries peaked in 1995.

Exploration spending peaked nearly 20 years later when the price per ounce averaged $1,600.

With gold now trading above $1,340 an ounce, up 26 percent for the year, many investors expect producers to begin lifting spending on exploration and production (or dividends).

Instead, most companies are in cost-cutting mode, using this opportunity to pay down debt and liquidate assets. According to Reuters, North American gold producers have managed to lower their debt levels 30 percent since late 2014.

Speaking to Mining.com, Newmont Mining (NYSE:NEM) CEO Gary Goldberg said his company, the second-largest gold producer in the world, is one of the few that’s currently building new mines—specifically the Merian project in Suriname and Long Canyon in Nevada. Because of the lack of new mines being built, he sees supply falling 7 percent between now and 2021.

Demand for the yellow metal, on the other hand, should remain strong during this period, helping to support prices even more.

Massive Inflows into Gold Funds

In the meantime, gold continues to find support from global monetary policy and low to negative government bond yields. Last week the Bank of England cut rates as part of a stimulus package, which both weakened the British pound 1.5 percent and gave the yellow metal a jolt.

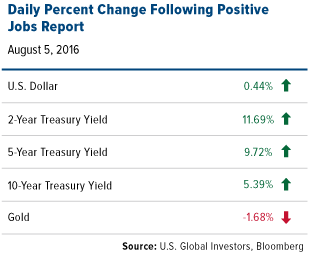

These gains were erased, however, following Friday’s better-than-expected U.S. jobs report, which sparked a rally in Treasuries. This contributes to the narrative that gold and government debt are inversely related, a key component of the Fear Trade.

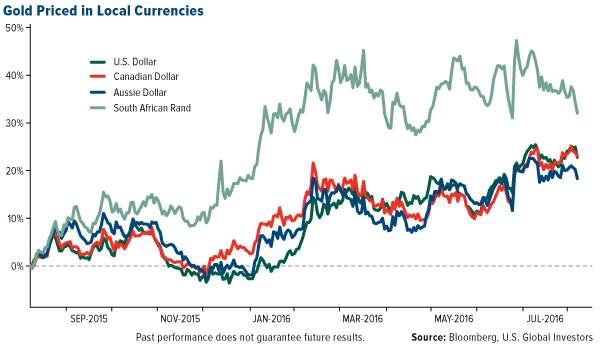

When priced in the local currencies of the U.S., Canada, South Africa or Australia—four of the largest gold-producing countries—bullion is up, which has boosted miners’ profits. Gold stocks, as measured by the NYSE Arca Gold Miners Index, have appreciated 128.92 percent in the last 12 months.

For the first half of 2016, inflows into commodities have been the strongest since 2009. Gold and other precious metals account for about 60 percent of the new money, which has pushed commodity assets under management above $235 billion. Barclays) believes 2016 could be the best year on record for gold-related ETFs and other funds, with many big-name hedge fund managers, from Stan Druckenmiller to Paul Singer to Bill Gross, singing the praises of the yellow metal.

Disclosure: All opinions expressed and data provided are subject to change without notice. Some of these opinions may not be appropriate to every investor. This commentary should not be considered a solicitation or offering of any investment product. Certain materials in this commentary may contain dated information. The information provided was current at the time of publication.