This past week I read some very diverse articles that I wanted to share with you. Hopefully, they will stimulate your grey matter over the weekend as you indulge in melted artifical cheese, processed fillers, and copious amounts of artificial colorings and flavors during the Super Bowl showdown (I am assuming you did not order any of the party packs).

In Thursday's missive I discussed the recent selloff and the likelihood that, despite yesterdays bounce, the correction process was likely not complete. However, one thing I did not get to was the "January Barometer."

I spend much of my time analyzing statistical data to help refine a strategic "guess" about the future. I recently reviewed the Decennial and Presidential Cycles which suggested that the current cyclical bull market likely has 18 to 24 months of life left. Over the next 11 months, the the Presidential Cycle suggested that it could be a more difficult year than what we enjoyed in 2013 by experiencing a greater than 10% correction during the summer months. That historical analysis is now being potentially supported by the "January Barometer."

The January Barometer, a theory that was initially postulated by Yale Hirsch in 1972, states that the overall gain or loss of the S&P 500 during the month of January will set the stock market's tone for the rest of the year. If the S&P ends January higher than the first trading day of the year, the market (as represented by the S&P) has generally trended higher for the rest of the year as well and vice versa if January ends in a loss.

Stock Trader's Almanac points out that:

"Statistically... In the 75-year history examined last Friday [1/18/2013], there were only 22 full-year declines. So yes, the S&P 500 has posted annual gains 70.7% of the time since 1938. What is missing from this argument is the fact that when January was positive, the full year was also positive 89.4% of the time and when January was down the year was down 60.7% of the time. Also, every down January on the S&P 500 since 1938, without exception, has preceded a new or extended bear market, a 10% correction, or a flat year."

With that tucked away here are some random things to ponder this weekend.

1) Is American Turning Japanese by J Bradford Long

I have discussed many times in the past, the economic and demographic similarities between Japan and the U.S. However, Mr. Long gives a very good history of Japan and how, at their peak of prosperity, they were not so very different from where the U.S. is today.

"With one-third the population of the United States, Japan was unlikely ever to become the world's preeminent economic superpower. But Japan would close the 30% gap (adjusted for purchasing power parity) between its per capita GDP and that of the US. The prevailing belief was that, by 2015 or so, Japan's per capita GDP would more likely than not be 10% higher than in the US (in PPP terms).

None of that happened. Japan's economy today is some 40% smaller than observers back in the late 1980's confidently predicted. The 70% of per capita US GDP that Japan achieved back then proved to be the high-water mark. Its economy-wide relative productivity level has since declined, with two decades of malaise eliminating the pressures to upgrade in agriculture, distribution, and other services."

It is a very interesting read.

2) Bank Regulator Fears Bubble And Warns Funds via Reuters

"The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency has already told banks to avoid some of the riskiest junk loans to companies, but is alarmed that banks may still do such deals by sharing some of the risk with asset managers.

'We do not see any benefit to banks working with alternative asset managers or shadow banks to skirt the regulation and continue to have weak deals flooding markets,' said Martin Pfinsgraff, senior deputy comptroller for large bank supervision at the OCC, in a statement in response to questions from Reuters.

Among the investors in alternative asset managers are pension funds that have funding issues of their own, he said.

'Transferring future losses from banks to pension funds does not aid long-term financial stability for the U.S. economy,' he added.

That may be happening with leveraged loan issuance, which hit a record $1.14 trillion in the U.S. in 2013, up 72 percent from the year before, according to Thomson Reuters Loan Pricing Corp (LPC).

A measure of the riskiness of these loans has also been rising - the average size of the debt for companies taking these loans in 2013 was 6.21 times a form of cash flow known as EBITDA or earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization, up from 5.86 times in 2012 and the highest since 2007, LPC said."

Is it just me, or have we seen this before?

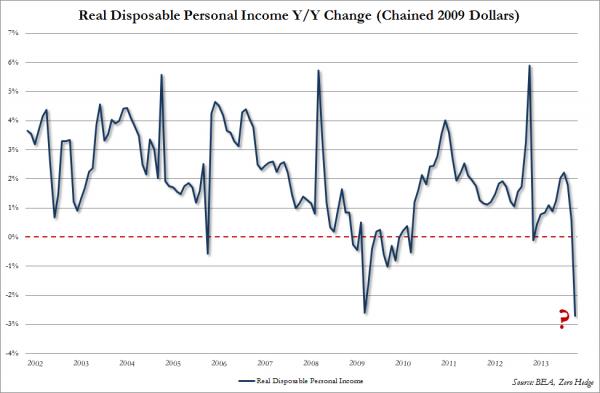

3) Real Disposable Income Collapses In December via Zero Hedge

I have been rather vocal as of late that the "pop" in GDP in the last half of 2013 was not a sign of economic liftoff, as hoped by many economists, but rather an inventory restocking cycle due to post Hurricane Sandy/Fiscal Cliff economic drag in the first half of the year. Considering that 70% of the economy is driven by personal consumption the latest reading on real disposable incomes does not suggest stronger economic growth in the coming quarters.

"We may not know much about "Keynesian economics" (and neither does anyone else: they just plug and pray, literally), but we know one thing: when real disposable personal income drops by 0.2% from a month earlier, and plummets by 2.7% from a year ago, the biggest collapse since the semi-depression in 1974, something is wrong with the US consumer."

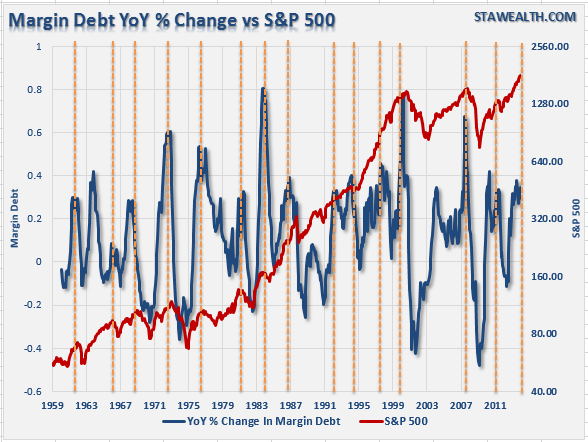

4) Margin Debt Surged In December via Pragmatic Capitalism

Cullen pointed out something very interesting in regards to margin debt.

"Of course, it would be silly to assume that this indicator is going to tell you when the market’s turning and I know a number of people have raised valid concerns about this metric, but I still find it to be a useful indication of broader sentiment. That is, as equities rally and euphoria increases we tend to see increasing levels of debt accumulation. And yes, we know that much of this is long only debt because short interest has actually been declining at the NYSE over the past 5 years. This is all consistent with the idea of a disaggregation of credit and the tendency for herding behavior to lead to increased euphoria as market participants view the bull market as increasingly invulnerable. Classic debt dynamics in an equity market cycle."

He is correct. There are many people that have dismissed the surge in margin debt as it has not immediately caused a market reversion. However, as I stated earlier this week:

"It is important to note that it is not the rise in margin debt that is the problem for the markets - it is the fall. When the ultimate reversal begins, and investors are forced to liquidate to meet margin calls, the market begins to feed upon itself. This forced liquidation quickly accelerates downside reversions in equity markets leaving investors little opportunity to react. The last two peaks in margin debts have had nasty outcomes for this very reason.

Lastly, spikes in margin date on an annualized basis (brought to my attention by my colleague Eric Hull) has typically marked either short term peaks are larger market corrections. This chart below is a log chart of the S&P 500. While this makes the chart easier to read, it also smooths some of the more relevant market reversion like Long Term Capital Management or the Asian Contagion in the late 90's."

5) 5 Steps To Strong Economic Growth via Forbes

As I stated above, there are many "hopes" for stronger economic growth in the 2014 and beyond despite the fact that we are already in one of the longest post-recession economic recoveries on record. While I have my own ideas for how to obtain stronger economic growth (lower tax rates, reduce regulations, etc.); David Malpass laid out some ideas worthy of consideration.

- Let interest rates rise.

- Rewrite the debt limit so it restrains spending growth.

- Yen ceiling

- Reduce the size of government

- Liberalize trade

He concludes with a most interesting point:

"Most governments plan to stay the course in 2014, hoping growth in other countries picks up enough to keep them in power. That’s possible, but each decision to maintain the status quo means slower job growth than that needed to meet the coming increase in the elderly population."

With everybody hoping that someone else is going to pull them out of the quicksand - who is left to do the pulling?