Many investors, especially those with limited investment experience, are declaring that value investing is dead.

If one’s investment experience runs over the last ten years, who can blame them? Since 2010, growth stocks have outperformed value stocks, on average, by 6.11% a year.

If one’s experience runs deeper, and/or they appreciate history, they may have a different perspective. Over the last 100 years, including the last ten, value has outperformed growth by 3.19% a year.

So, is value dead or does value offer incredible opportunities versus growth?

All value and growth data in this article comes from Kenneth French and Dartmouth University. In particular, we use the HML factor from the Data tab.

What are Value and Growth?

Value stocks can be defined in many different ways. The basic premise, however, is the inclusion of stocks trading at a low price relative to their fundamentals; low price-to-earnings, low price-to-book, low price-to-sales, etc. The benefit of buying value stocks is the expectation that prices return to fair value. Quite often, the return benefits from above-market dividends. Equally important, buying a discounted asset reduces your risk.

Like value, there is no simple formula defining growth stocks. Growth stocks are companies whose earnings are expected to grow at a faster rate than the market. Because of the promise of future earnings, these stocks tend to trade at valuation premiums. Fewer of these stocks have meaningful dividends to bolster returns. Assets trading at a premium have a more daunting risk profile.

There is an appeal to owning value stocks and growth stocks. Mr. Market, however, makes deciding between the two difficult. At times, the premium for growth stocks can far exceed their potential growth. Frequently in such times, value is neglected and offers enormous relative performance potential. Other times growth stocks may be beaten down and offer a cheap entry point versus value stocks that have traded up to, or through, their fair value.

Historical Perspective

We firmly believe in mean reversion. The extreme highs for one asset class will eventually normalize closer to the long-term average. Often this occurs after dropping well below the long-term average. There is no example in the history of markets where mean reversion did not exert influence.

As mentioned, value has underperformed growth annually by 6.11% over the past decade. Over the last 100 years, value beats growth by 3.19% annually.

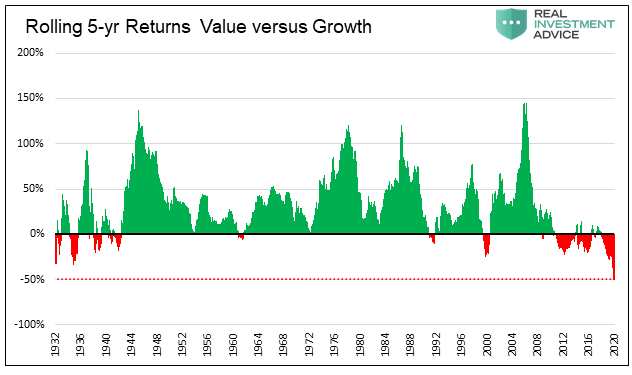

The graph below shows the rolling five year total returns for value versus growth.

As shown, there are very few five year periods where growth beats value. 82 percent of the time value outperforms growth. If we exclude the last ten years and the 1930’s the percentage climbs to 96%.

It is also notable that periods of value underperformance are followed by periods of strong outperformance. As we will highlight, this was last on display in the technology bubble of the late 1990s. From July of 2001 to July of 2006, value outperformed growth by nearly 150%.

As the chart above illustrates, the current period of value underperformance is the most extreme both in terms of duration and magnitude. Mean reversion argues that this trend will soon shift back to favor value.

Tech Boom and Bust

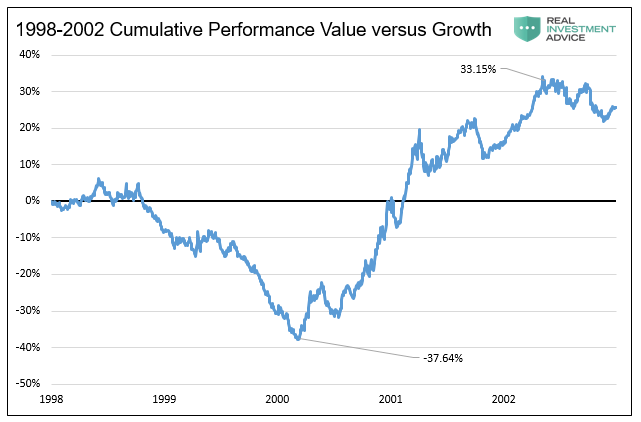

The graph below details the value-growth under- and outperformance of the late 1990s and early 2000s.

The chart tracks the cumulative net performance of value stocks versus growth stocks between 1998 and 2002. Like today, investors caught up in the tech boom only cared about growth. They bought into every story about the promise of technology. At the same time, companies trading with low valuations and steadily rising earnings are being thrown by the wayside.

In just two years, as markets rose to record-breaking valuations, growth beat value by 37.64%. However, when the markets came to their senses in early 2000, value rose from the dead. From low to high, just two years later, value beat growth by over 70%.

Value investors that held to their beliefs, stuck with their discipline, and shunned growth stocks may have lost the day in the late 1990s but won the battle. Not only did value stocks provide a great return but they provided a nice cushion. Owning value stocks in the early 2000s not only limited losses but actually produced gains in a down market.

20 Years Later

The experiences of the tech boom and bust have been long forgotten by most investors. There are a few value investors remaining today who are aware of what happened then. Like then, they are waiting for a second showing, but the wait is tedious.

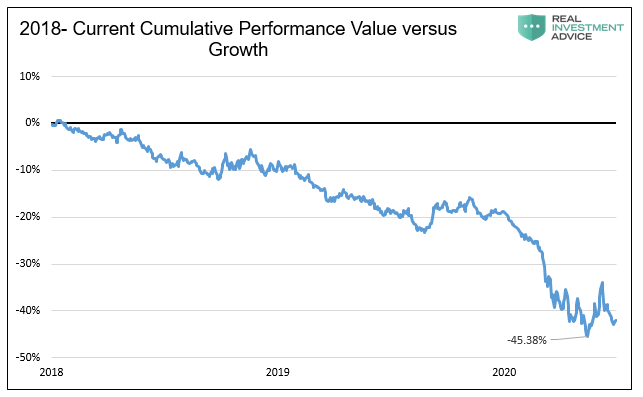

The graph below shows that over the last two years growth has beaten value by 45%, 7% more than the two years leading into the tech bust.

Like the 1990s, every investor is chasing the same set of growth stocks. Today, they go by the name of FANGS. In the late 90s, they were called the Big Five.

The magnitude growth outperformance is amplified today due to the overwhelming popularity of passive investing. Those companies with the largest market caps receive a disproportionate percentage of investable dollars. Companies with the largest market caps today are predominantly growth companies.

2000 vs 2020

While the two periods may appear similar in their speculative nature and the value – growth divide, their fundamental backdrops are worlds apart.

In 2000, share prices of growth stocks, and in particular specific tech high flyers, got ahead of themselves. Their future earnings, however, had strong economic and fundamental underpinnings. Today they do not.

GDP was growing annually at 3.2% in the 1990s. That compares to 2% over the last ten years and most likely below 1.5% in the future. In the 1990s, debt as a percentage of GDP was a fraction of what it is today. Productivity growth was much stronger twenty years ago than today as well. In the 1990s, companies invested in their future development. Today they prefer to buy back stock and neglect their future earnings capabilities.

Today’s economy is not backed by organic growth and strong productivity, but rather debt and fiscal and monetary schemes. Given the environment, the argument for speculation over reliable earnings growth is befuddling.

Summary

If you appreciate history and understand that hangovers follow periods of excess, this article should be compelling. Growth’s recent outperformance over value goes beyond any historical precedence. Accordingly, any future underperformance, like its outperformance, might be one for the record books.

Exact timing on trend changes are difficult to predict. Growth may have already peaked versus value, or it may still have months or years to go. Regardless, the current period provides us precious time. Time to research stocks and slowly add value stocks to our portfolios. Adding value may seem futile like the late 1990s, but we know how that ended.