Correspondence with a longtime Camp Kotok fishing partner concerning some interesting omissions from the Fed’s most recent semiannual report to Congress piqued my curiosity as to how feasible would it be for the Fed to simply let its portfolio run off as it sought to return policy to a more normal stance, and what would happen if it did. Everyone is well aware that the Fed now holds about 30% of all outstanding Treasury notes and bonds. (That percentage can be calculated from data on the Fed of NY’s website). If the Fed stopped rolling over maturing securities in its portfolio and the Treasury replaced them with new issues, this move might relieve some of the pressure in the market; but there are some interesting issues associated with that scenario, having to do with the maturity structure and composition of the Fed’s portfolio.

The Fed’s H.4.1 weekly release can provide some clues as to the issues, but the maturity categories are very coarse. For example, the July 23 release shown in Table 2 provides a maturity breakdown that reveals the Fed has essentially no short-term securities maturing in less than a year, while it has $1.099 trillion maturing between one to five years, only about $570 billion maturing between five and ten years, and slightly more than $2.3 trillion maturing in over ten years. These gross amounts don’t really highlight the real problem, however. Fortunately, the New York Fed publishes weekly data on each individual security it holds in the System Open Market Account (SOMA). The data contain the maturity date as well as the original maturity, par value (for Treasuries and agency securities), and remaining face value for each MBS (there are over 80K individual MBS CUSIPs listed). With those data, we can achieve more granularity with regard to the maturity issue.

The maturity issue is important because of timing and because there are only three ways to shrink the Fed’s portfolio as it returns policy to a more normal stance. The Fed can simply let its assets run off; it can sell assets; or the banking system can shrink by letting bank loans run off, thereby reducing deposits and, correspondingly, bank reserves held at the Fed. The third option is clearly not desirable, because it would slow economic growth or even shrink it. Selling assets into the market would obviously provide needed liquidity in the form of Treasury securities, but those sales would most likely have to take place at a loss in a rising-interest-rate environment that the Fed would have to recognize. We have written previously on what those losses would mean, how they would be recognized, and how they would affect remittances to the Treasury.

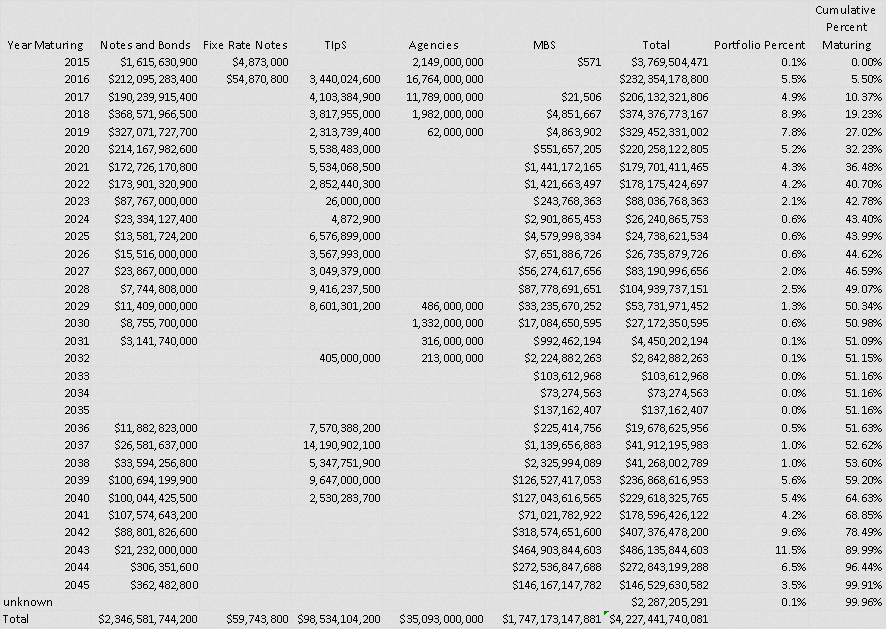

So, how quickly could the Fed shrink its balance sheet by not rolling over maturing issues, thereby reducing both excess reserves of the banking system and the threats they might pose to an expansion of the money supply and subsequent inflation? The following table shows the estimated maturity distribution of the Fed’s portfolio (calculations based upon data on asset composition of the SOMA portfolio on the FRB NY website), what securities are scheduled to mature, and when. We see that only $3 billion of assets, mainly agency securities and Treasury notes and bonds, will mature during the rest of 2015; $232 billion of assets will mature in 2016; and another $205 billion will mature in 2017 (a total of only about 10% of the Fed’s portfolio). It would take a full 15 years for 50% of the portfolio to mature.

It seems clear that given a shrinking federal deficit, the small volume of maturing securities in the Fed’s portfolio will hardly make a perceptible dent in the so-called shortage of liquid assets in the marketplace.

Note too that there is an asymmetry in maturity structure in terms of the kinds of assets the Fed holds. Treasury and agency securities dominate assets maturing in the next six years, while MBS and long-term Treasuries dominate the out years.

So why does this maturity structure pose a dilemma for the Fed and FOMC? The lack of run-off in the first two years, combined with the potential problems associated with selling assets, means that sterilization of the excess reserves in the system puts a heavy burden on interest-rate policy to keep the money supply and inflation in check. This suggests careful thought must go into structuring the rate corridor and the relative rate paid on reserves, the discount rate, and the reverse repo rate. We don’t know what the interest costs of the resulting policy will be, but they could be very high if inflation and market rates accelerate such that the interest costs exceed the interest rate earned on assets held in the portfolio. This imbalance could potentially trigger losses that would be booked in a negative asset account to be filled by future revenues on holdings of Treasury obligations rather than by writing down the Fed’s equity. The result would mirror the costs of simply selling assets. Finally, if economic growth and inflation accelerate, then the burden on the reverse repo market might outstrip the market’s appetite for those short-term assets.

Digging a bit deeper, the total reduction in the size of the portfolio would not require reducing it to the pre-crisis level, where the size of the portfolio was conditioned by the volume of currency outstanding. The Fed is required to hold eligible assets as a backstop that would supposedly allow it to collateralize outstanding Federal Reserve notes (we set aside the perverse logic as to how one government liability like Treasury or agency debt can serve as collateral for another government liability in the form of Federal Reserve notes).

Traditionally, the Fed has sought to provide currency as it is demanded to facilitate exchange. This process has meant that currency outstanding expanded at a pace to meet the growth in nominal GDP. For example, from 2000 through 2014 nominal GDP grew at a compound rate of 3.6%, whereas currency grew at 5.7%. (Virtually all of this growth was accounted for by the increase in $100 bills, which grew at the compound rate of 6.8%. We know that a large portion of this cash is held outside the US.)

Remember that about 50% of the Fed’s portfolio will mature by 2029, that is, in 15 years. If currency expanded at just the recent rate of growth in nominal GDP, then outstanding currency would be $2.2 trillion then; and, hence, the Fed’s “normal” balance sheet would be somewhat in excess of that amount. If currency expanded at its recent rate of 5.7%, this would imply a Fed balance sheet somewhat in excess of $2.7 trillion. So by 2029 the normal maturation process would leave the Fed’s balance sheet at about $2.1–$2.7 trillion and be only about $100 to $500 billion short of what it should be, with virtually no outstanding excess reserves.

The problem is that, because of the mix of long-term assets held by the Fed, $1.5 trillion of those assets would be MBS, and $500 billion would be long-term Treasuries. Under present law, including Sections 13 and Section 14 of the Federal Reserve Act (and the 1966 Interest Adjustment Act), the Fed is authorized to purchase and hold assets backed by Freddie and Fannie. But two things have changed. First, the two GSEs failed during the financial crisis and are presently in government receivership. Right now that doesn’t matter, since they are essentially government entities. However, should they be privatized, as is being proposed, then provisions of the recently passed Dodd-Frank Act would prohibit the Fed from purchasing assets from private-sector entities.

In summary, the maturity structure and runoff of the Fed’s portfolio suggest that devising a strategy that would simply let most of the Fed’s portfolio mature and run off could be managed, in part because the growth in currency demand (assuming electronic payment mechanisms like Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL) Pay don’t slow that growth) would over time enable the Fed to meet its collateral requirements with the existing volume of long-duration assets in its portfolio. Whether there is a potential problem with the composition of those assets is another question. For example, predicting the exact maturity structure of the MBS and the payment stream flowing from those assets depends upon both the interest-rate environment and upon how borrowers exercise their prepayment options. The bottom line is that the key to managing the return to policy normality lies in effectively managing short-term interest rates via the Fed funds market and perhaps the reverse repo market, especially in the next two or three years. There remain earnings and accounting problems should credit growth, interest rates, and inflation accelerate. These are not easy problems, and ones that don’t appear yet to have generated a consensus among the FOMC participants, and is another reason why a policy move at the July FOMC meeting is problematic.

Bob Eisenbeis, Vice Chairman & Chief Monetary Economist.