Last week, I discussed the issue of “bubbles” in the market. To wit:

Market bubbles have NOTHING to do with valuations or fundamentals.

Hold on…don’t start screaming “heretic” and building gallows just yet. Let me explain.

Stock market bubbles are driven by speculation, greed, and emotional biases – therefore valuations and fundamentals are simply a reflection of those emotions.

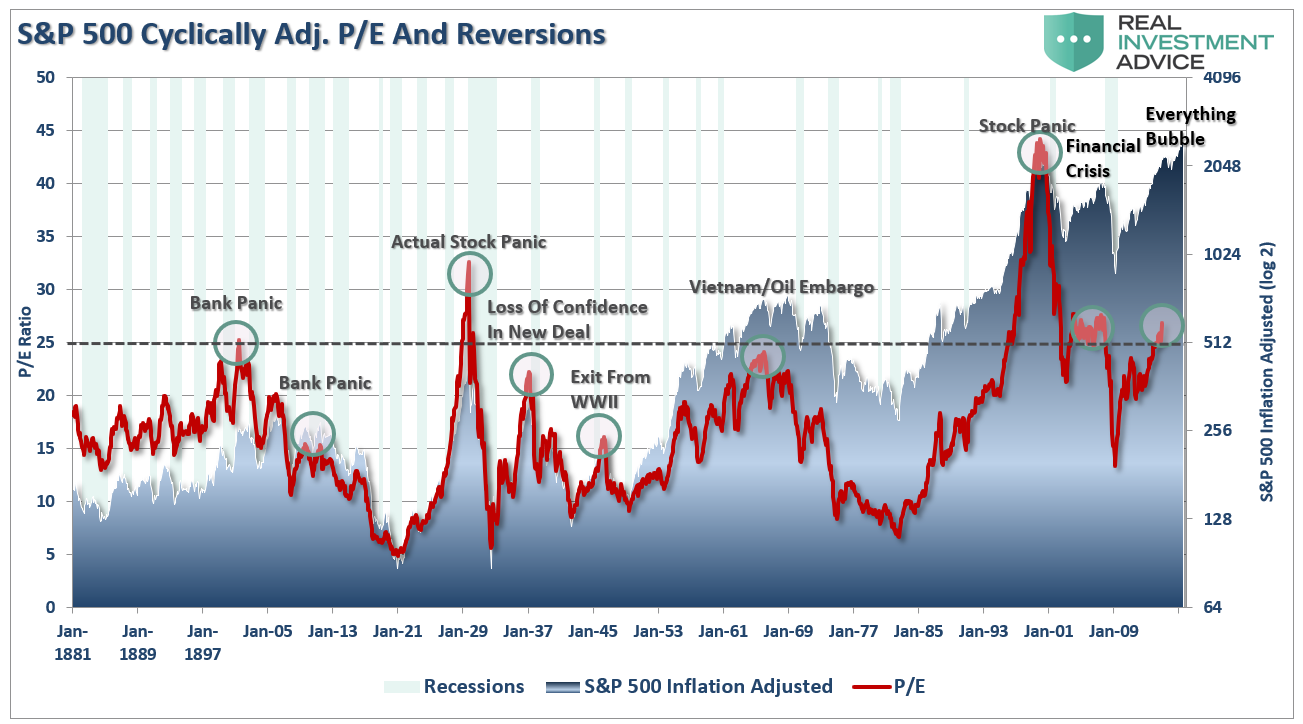

In other words, bubbles can exist even at times when valuations and fundamentals might argue otherwise. Let me show you a very basic example of what I mean. The chart below is the long-term valuation of the S&P 500 going back to 1871.

First, it is important to notice that with the exception of only 1929, 2000 and 2007, every other major market crash occurred with valuations at levels LOWER than they are currently. Secondly, all of these crashes have been the result of things unrelated to valuation levels such as liquidity issues, government actions, monetary policy mistakes, recessions or inflationary spikes.

However, those events were only a catalyst, or trigger, that started the ‘panic for the exits’ by investors.

Market crashes are an “emotionally” driven imbalance in supply and demand. You will commonly hear that “for every buyer, there must be a seller.” This is absolutely true. The issue becomes at “what price?” What moves prices up and down, in a normal market environment, is the price level at which a buyer and seller complete a transaction.

The problem becomes when the “buyer at a higher price” fails to appear.

The markets function much the same way as yelling “fire” in a theater filled to capacity with only one exit. Those closest to the exit will likely get out safely, but once the “bottleneck” forms, there is an inability to exit before the damage is done.

The “exit” problem is exacerbated when “everyone is in the same theater.”

Dana Lyons observed this last week.

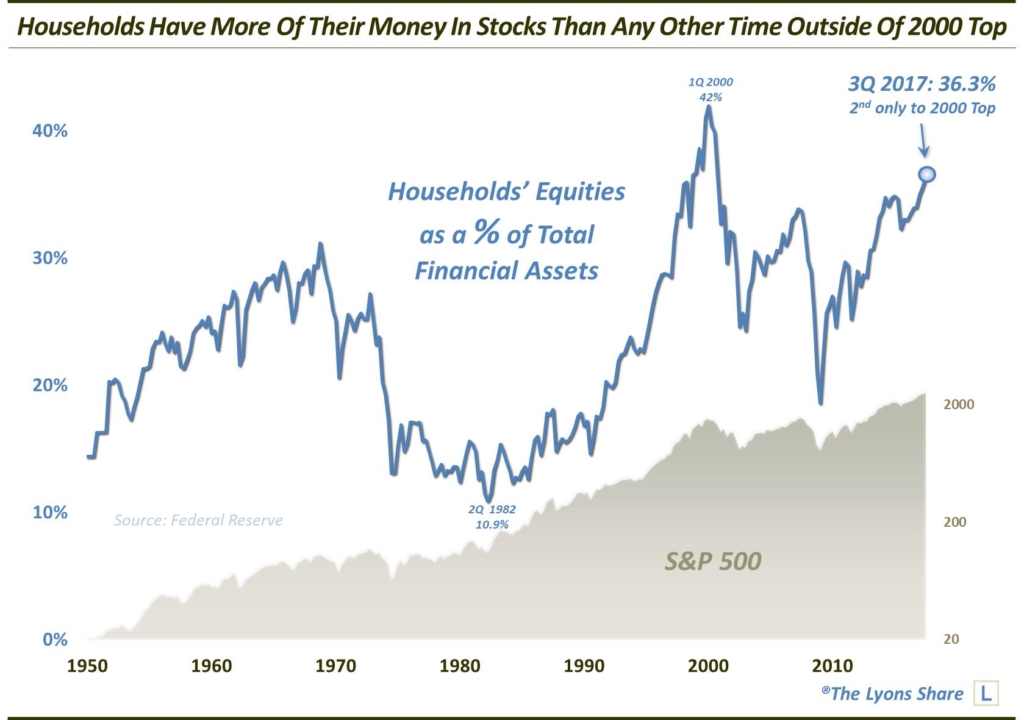

The percentage households’ financial assets currently invested in stocks has jumped to levels exceeded only by the 2000 bubble.

Updating one of our favorite data series from the Federal Reserve’s latest Z.1 Release, we see that in the 3rd quarter, household and nonprofit’s stock holdings jumped to 36.3% of their total financial assets. This is the highest percentage since 2000. And, in fact, the only time in the history of the data (since 1945) that saw higher household stock investment than now was during the 1999 to 2000 blow-off phase of the dotcom bubble. Perhaps not everyone is in the pool, but it certainly is extremely crowded.

Note how stock investment peaked with major tops in 1966, 1968, 1972, 2000 and 2007. Of course, investment will rise merely with the appreciation of the market; however, we also observe disproportionate jumps in investment levels near tops as well. Note the spikes at the 1968 and 1972 tops and, most egregiously, at the 2000 top.

Yes, there is still room to go (less than 6 percentage points now) to reach the bubble highs of 2000. However, one flawed behavioral practice we see time and time again is gauging context and probability based on outlier readings. The fact that we are below the highest reading of all-time in stock investment should not lead one’s primary conclusion to be that there is still plenty of room to go to reach those levels.

Sitting Closer To The Exit

Howard Marks once stated that being a “contrarian” is tough, lonely and generally right. To wit:

Resisting – and thereby achieving success as a contrarian – isn’t easy. Things combine to make it difficult; including natural herd tendencies and the pain imposed by being out of step, particularly when momentum invariably makes pro-cyclical actions look correct for a while. (That’s why it’s essential to remember that‘being too far ahead of your time is indistinguishable from being wrong.’)

Given the uncertain nature of the future, and thus the difficulty of being confident your position is the right one – especially as price moves against you – it’s challenging to be a lonely contrarian.

The problem with being a contrarian is the determination of where in a market cycle the “herd mentality” is operating.

The collective wisdom of market participants is generally “right” during the middle of a market advance but “wrong” at market peaks and troughs.

This is why technical analysis, which is nothing more than the study of “herd psychology,” can be useful at determining the point in the market cycle where betting against the “crowd” can be effective. Being too early, or late, as Howard Marks stated, is the same as being wrong.

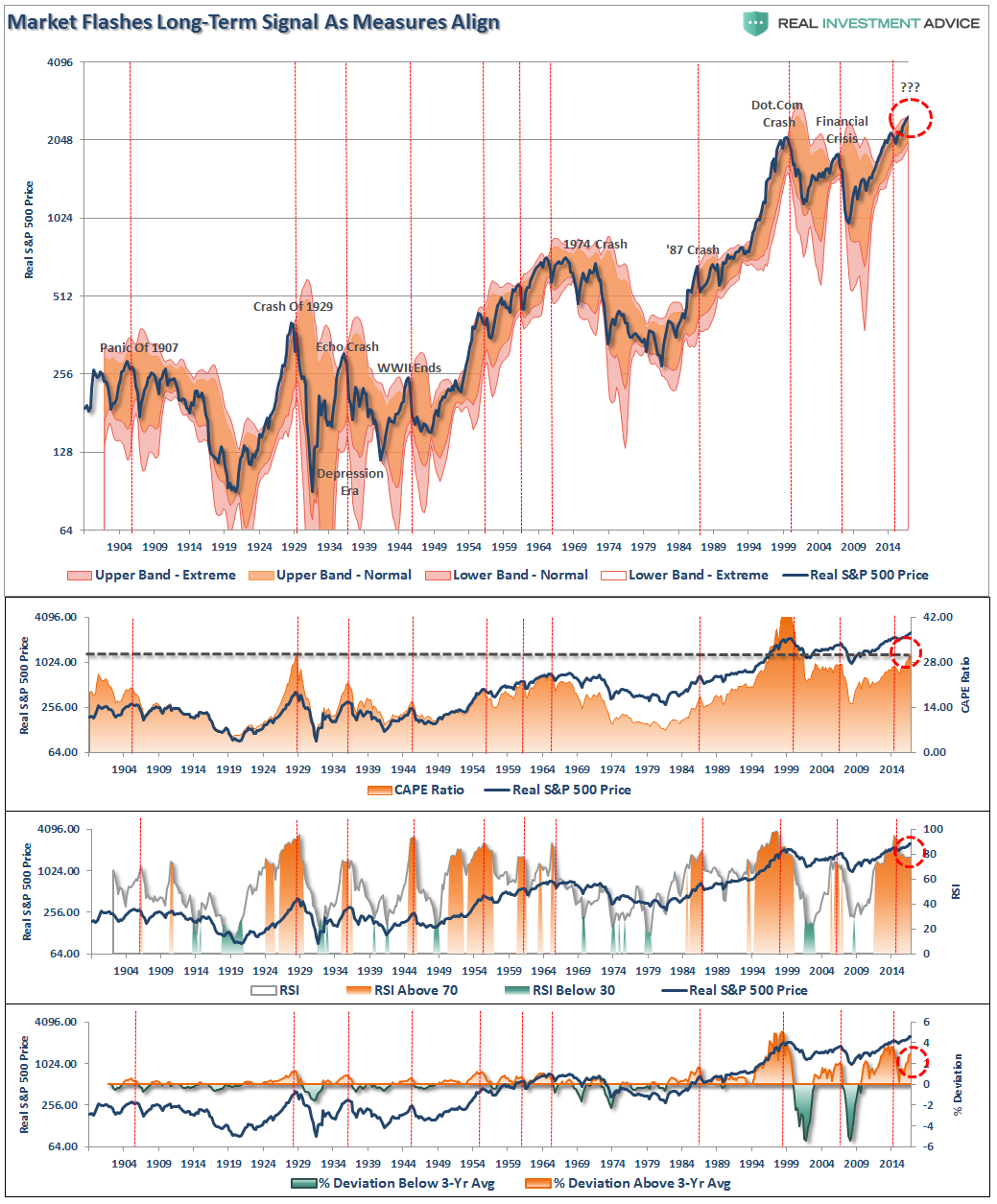

The chart below is a historical chart of the S&P 500 index based on QUARTERLY data. Such long-term data is NOT useful for short-term market timing BUT is critically important in not only determining the current price trends of the market but potentially the turning points as well.

- The 12-period (3-year) Relative Strength Index (RSI),

- Bollinger® Bands (2 and 3 standard deviations of the 3-year average),

- CAPE Ratio, and;

- The percentage deviation above and below the 3-year moving average.

- The vertical RED lines denote points where all measures have aligned

While valuation risk is certainly concerning, it is the extreme deviations of other measures to which attention should be paid. When long-term indicators have previously been this overbought, further gains in the market have been hard to achieve. However, the problem comes, as identified by the vertical lines, is understanding when these indicators reverse course. The subsequent “reversions” have not been forgiving.

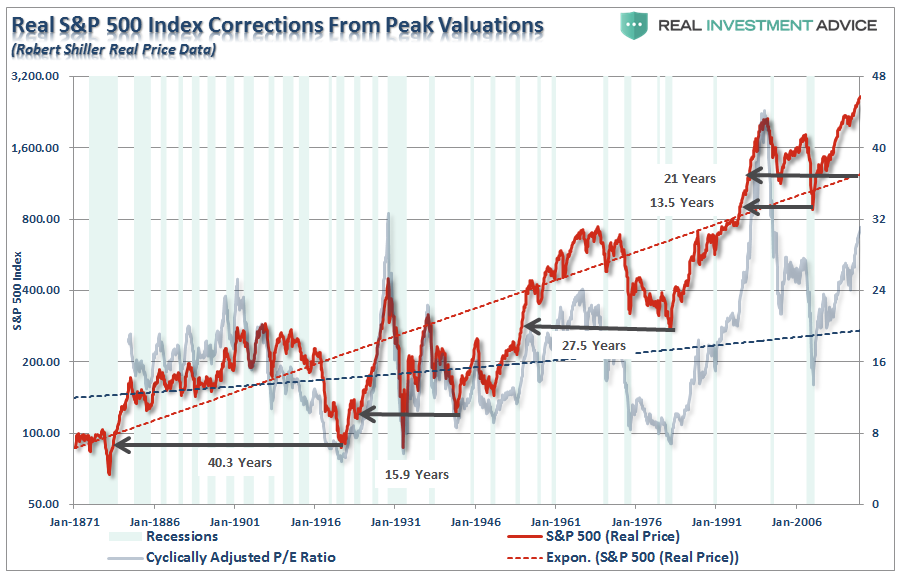

The chart below brings this idea of reversion into clearer focus. I have overlaid the real, inflation-adjusted S&P 500 index over the cyclically adjusted P/E ratio.

Historically, we find that when both valuations and prices have extended well beyond their intrinsic long-term trendlines, subsequent reversions beyond those trend lines have ensued.

Every. Single. Time.

Importantly, these reversions have wiped out a decade, or more, in investor gains. As noted, if the next correction began in 2018, and ONLY reverts back to the long-term trendline, which historically has never been the case, investors would reset portfolios back to levels not seen since 1997.

Two decades of gains lost.

With everyone crowded into the “ETF Theater,” the “exit” problem should be of serious concern.

Over the next several weeks, or even months, the markets can certainly extend the current deviations from long-term mean even further. But that is the nature of every bull market peak, and bubble, throughout history as the seeming impervious advance lures the last of the stock market ‘holdouts’ back into the markets.

Unfortunately, for most investors, they are likely stuck at the very back of the theater.

With sentiment currently at very high levels, combined with low volatility and excess margin debt, all the ingredients necessary for a sharp market reversion are currently present.

Am I sounding an “alarm bell” and calling for the end of the known world? Should you be buying ammo and food? Of course, not.

However, I am suggesting that remaining fully invested in the financial markets without a thorough understanding of your “risk exposure” will likely not have the desired end result you have been promised.

As I stated often, my job is to participate in the markets while keeping a measured approach to capital preservation. Since it is considered “bearish” to point out the potential “risks” that could lead to rapid capital destruction; then I guess you can call me a “bear.”

Just make sure you understand I am still in “theater,” I am just moving much closer to the “exit.”